|

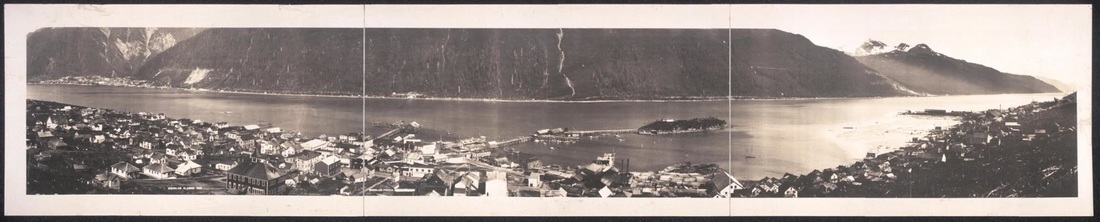

By Katy Ritter Gastineau Elementary, 4th Grade I was scheduled to use the 4th grade elementary art kit, Centennial Bridge, but I’d never used it before. I didn’t check it out with a purpose to integrate it into our current social studies or science units of study, but I was excited to try an Artful Thinking Routine that would add some depth to our discussion, and hopefully deepen students’ engagement in the lesson. I decided that I would begin by showing the photographs of the Gastineau Channel/Douglas Bridge included in the kit, and use the Think/Puzzle/Explore routine. I hoped that showing the photographs without telling any information would invite students to try to build a narrative about the history of transportation in Juneau. I displayed the photographs on my whiteboard tray at the front of the room, and asked students to look at them carefully and quietly without talking. I began with the question, “What do you THINK you know about this topic?” Some of their responses:

Students seemed to understand that all of the photographs were connected, and they were telling a sequential story of the transportation used in the Gastineau channel. Then I asked, “What questions or puzzles do you have?

And the final question: "What does this artwork or topic make you want to explore?"

Students were very engaged and excited to find out that the reason the old bridge was replaced was because it was too small for the growing population and the new bridge is larger (this could be linked to why the roundabout was built about ten years ago!) They commented on the structure of each bridge and the difference in design, wondering why the old bridge had more artistic detail.

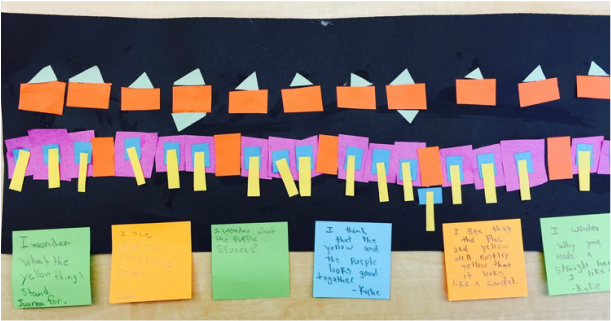

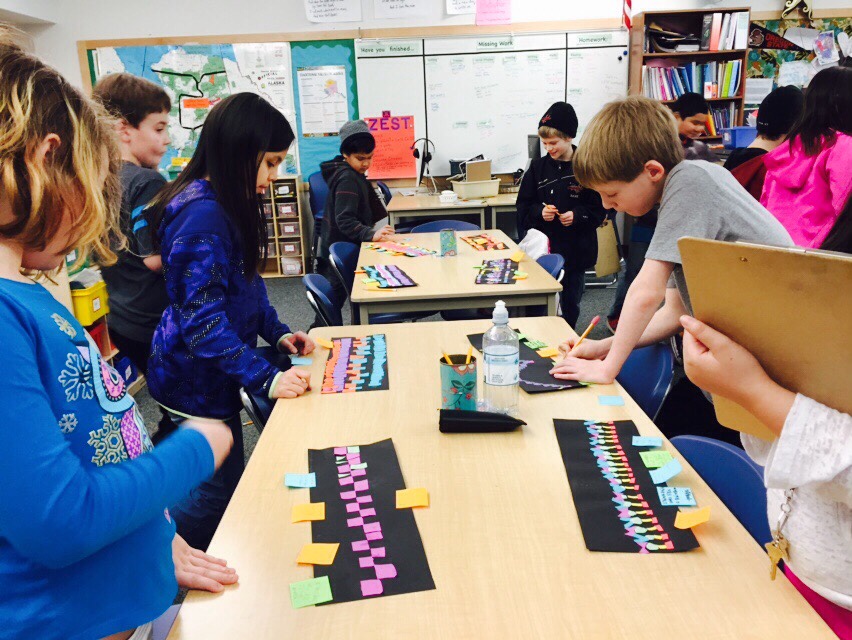

I introduced the photographs of the Centennial bridge and we compared it to the Douglas Bridge. We determined that it looks like a pedestrian bridge, which is why the art decorating the two sides of the bridge is in the footpath. We looked carefully at the symbolic images placed on either side of the bridge and thought about the difference between art that is functional (like a bridge, which has a form and a function) and the Centennial bridge, that includes style which carries symbolic MEANING. Students then created abstract bridges with 100 pieces of colored paper, creating patterns and lines. The results are as different as my students--each created their own pattern or arrangement of color and shape on the page.

0 Comments

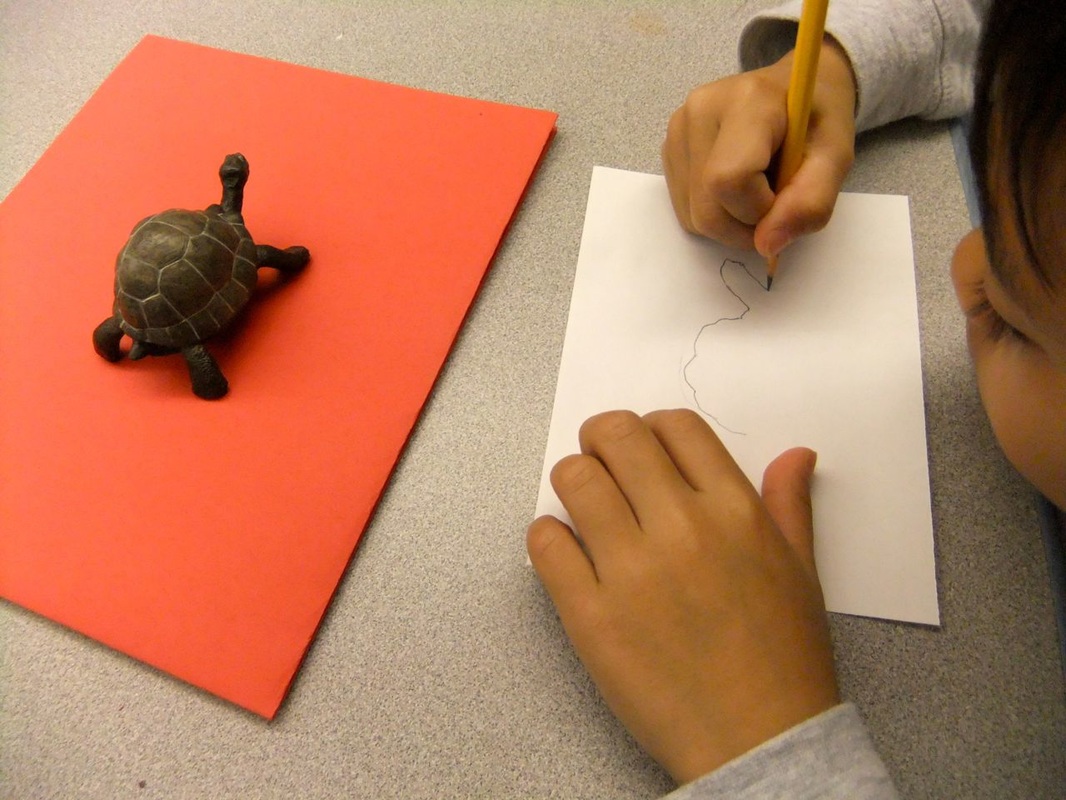

by Nancy Lehnhart JSD Elementary Art Specialist I’m not sure why it is, but kids seem to put a lot of stock in drawing as the quintessential qualification for being an artist. When you ask them if they know any artists, they will almost always tell you about someone they know who can draw. I was really curious about this early in my art teaching work, and also noticed that at a pretty young age, most kids decide they can’t draw (and therefore are not an artist.) And it was actually true; the development of their drawings seemed to stay at about a 2nd or 3rd grade level. Indeed, most adults will tell you they “can’t draw a straight line” and if pressed to draw something, you might confuse their drawings with a kid. I guess we just can’t keep very complex symbols in our heads, most of us, so if we’re trying to reproduce these simple symbols we have memorized, it stays pretty elementary. Somewhere in my early years of teaching I learned about the Reggio Emilia schools in Italy. I was mostly fascinated by the drawing these kids were doing, and how drawing was incorporated into learning as a tool for observation and investigation. I started experimenting with the young children I was working with, both at Juneau Co-op Preschool and in my own kids classrooms in elementary schools. I used a lot of the Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain language, brought down to a young child’s level. And I was impressed! Young children really did seem to take to it naturally. Their drawings were amazingly realistic, even while they were still delightfully quirky as a child’s drawing. Because of this, I’ve become pretty zealous about teaching and encouraging kids at all grade levels (and adults!) to practice drawing from observation. Which basically means, find something to use as a model, (a feather, a worm, a car, a very still friend, a photo,etc.,) observe it closely, resist drawing a pre-conceived “symbol” for it, and slowly, draw the shapes and lines you see. You’ll be impressed with yourself. Anyone can learn to draw this way. And it’s not that drawing makes an artist, but why not make sure kids know they can learn to do it if they want to!

Over the years of developing art kits for the Juneau School District, I’ve made sure there is a “drawing from observation” art kit for each grade level and I’m kind of preachy about it. I was worried that if teachers did too much of the “This is how you draw a dog,” step by step stuff, kids would learn to see drawing as steps you had to memorize, and if you couldn’t remember a step, well, you just couldn’t draw a penguin or bear or whatever. I wanted them instead to know you simply just needed to find a picture of a penguin (or a real one) to look at and you could draw it very convincingly from observation—and this is actually what most artists do—most artists don’t draw things out of their heads! |

ArtStoriesA collection of JSD teachers' arts integration classroom experiences Categories

All

|

|

|

Artful Teaching is a collaborative project of the Juneau School District, University of Alaska Southeast, and the Juneau Arts and Humanities Council.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed