|

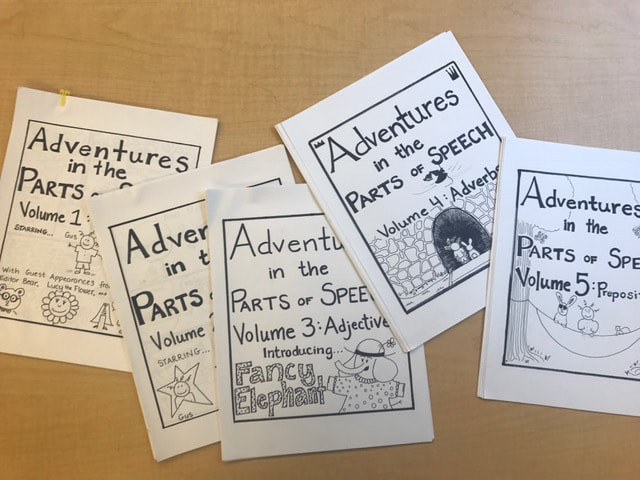

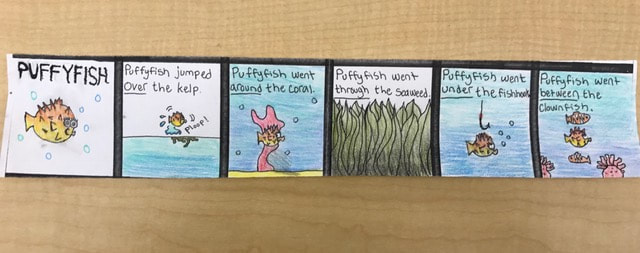

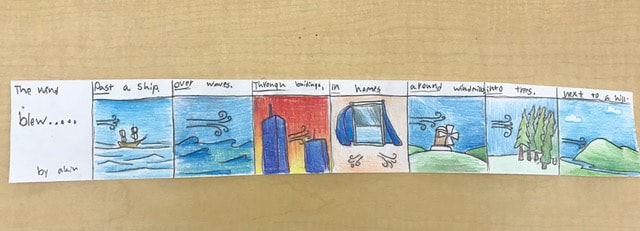

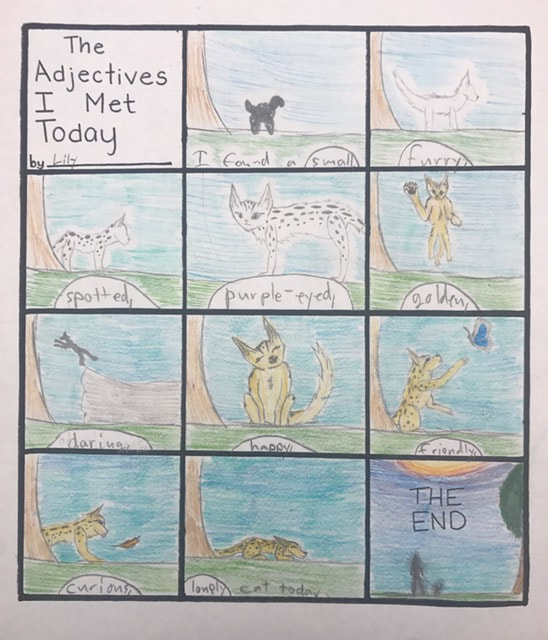

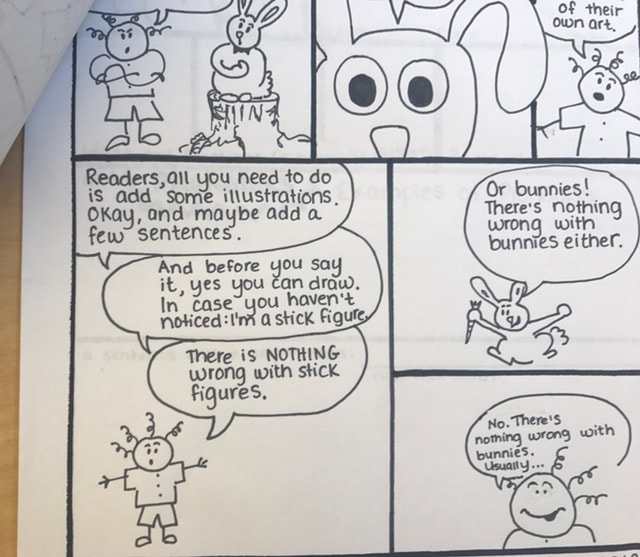

By Samantha Davis 8th Grade Language Arts, Floyd Dryden Middle School As I began my year in Artful Teaching, I was so excited to learn new ways of integrating arts into my eighth grade language arts classroom. During a fall unit about the parts of speech, I set a goal of working art into grammar instruction, both through the products students create to show their learning and through my own teaching methods. Though I eventually added in some of the strategies I was learning about in the Artful Teaching workshops, including tableau, I primarily focused on integrating comics into the parts of speech unit. Our learning objective was for every student to show their understanding of the parts of speech through a series of mini-comics. Because I wanted to begin our learning with a form that integrated art into instruction, I created short comic books introducing students to each of the eight parts of speech. As students moved through the unit, they learned to expect that each new concept would both begin and end with a comic: they’d learn about the part of speech through a comic, and they’d eventually produce a comic showing their understanding of the part of speech. We’d start by reading a comic about the part of speech aloud in class. Voices were strongly encouraged, and the actors in class often rose to the occasion, much to their classmates’ amusement. These comics not only introduced the content-area concept, it also forced me to take the same risk I'd be asking students to take: creating and sharing original artwork. This helped create a safe environment for creating and making mistakes. After we read the introductory comic, we’d discuss the part of speech, practice identifying it in different sentences, analyze why it matters in writing, and respond to writing prompts focused on that particular part of speech. Finally, students would show their knowledge of the part of speech through their own comics. The prompts for these comics were designed to encourage creativity, provide structure, and focus on the objective. For example, one comic was called, “The Adjectives I Met Today.” For this comic, students would pick a noun and invent a variety of adjectives for that noun to “meet.” Students used the artwork to (literally) draw connections between nouns and adjectives, thus representing the abstract concept of nouns modifying adjectives in a concrete, visual way. For the students’ preposition comic strips, the prompt involved picking a noun or pronoun and an action verb. Then, every successive frame had to be a prepositional phrase. Again, students were using art to demonstrate their understanding of an abstract concept. While the prompt and the prepared templates gave even more reluctant students the confidence that they could be successful, students were encouraged to extend and adapt the prompt as well. In every class, some students would take the initial prompt in new directions, without losing their ability to demonstrate their understanding of the content goals. In these situations, students would approach me with a proposal for another approach—“What if I…”—and we’d discuss how that approach would still work to show understanding of the content goals, or we’d modify it so it would still show the understanding while honoring the student’s unique approach. Some students were reluctant about their drawing skills. But stick figures were okay: after all, the star of “Adventures in the Parts of Speech” is a stick figure. In some ways, this approach to these projects helped establish a classroom culture where the expectation is not to avoid mistakes, but to try even when we’re unsure. Finally, one of my favorite moments of this unit--and in every unit in which students produced a piece of visual art--is the moment when the student work is displayed in the back of the classroom (our classroom gallery). Without fail, the day after their work is posted, students gather to observe the creations—always searching for their own, but also seeing how others responded to the same prompt in completely different ways. Often, they’re also assessing learning and asking new questions about the concepts. In the days and weeks after I post their work, I will often find students, on their own or with their classmates, browsing the gallery. So in this final stage, students are learning from each other.

So, why was it important for students to construct and demonstrate their understanding through the arts? First of all, I found students far more ready to engage with a pretty dry concept—the parts of speech isn’t exactly the stuff of fireworks—when it was introduced in the fun, humorous, and accessible medium of comics. Furthermore, when students began creating their own comics, it allowed for on-the-spot formative assessment along with natural extensions. It was easy to see which students had a mastery of the concept and which still needed more one-on-one instruction. Plus, with students so engaged in the project, it often gave me to provide that extra instruction as soon as I identified the need for it. Even more importantly, I’ve found that the use of art to show understanding builds community in the classroom. It forges connections: students who feel more confident in their artwork can encourage and support those who feel more apprehensive about their drawing skills, while students who felt more confident about their understanding of the content concept (in this situation, the parts of speech) can question and guide those who might still be confused. Comics--whether students are reading them or creating them--invite humor and conversation. In the classroom, as students worked on their comics, there was a constant buzz of conversation as they checked their understanding and ideas with each other. While everyone created their own comic, they worked together to create, sharing and exchanging supplies—“Can I use that crayon?” “No, I’m not done with it quite yet” “Oh, here, I have one you can use”—in ways that felt natural and needed no prompting from the teacher. Similarly, students began to use the artful thinking disposition of see-think-wonder before it’d been formally introduced, as they shared their work with each other, making observations and asking questions. The work was both individual and collaborative. When I think about this question, “Why was it important for students to construct and demonstrate their understanding through the arts?”, I think about these scenes: students gathering in front of the gallery to see, think, and wonder about each other’s work; students sharing art supplies and ideas; students laughing and celebrating each individual’s unique approach to a project. In short, when students construct their learning through the arts, it encourages both individual creativity and a supportive classroom community. Though I’m in my twentieth year of teaching, my participation in Artful Teaching has consistently provided me with new challenges, ideas, and inspiration over the course of the year; I’m already looking forward to building on all I’ve learned this year with next year’s students.

0 Comments

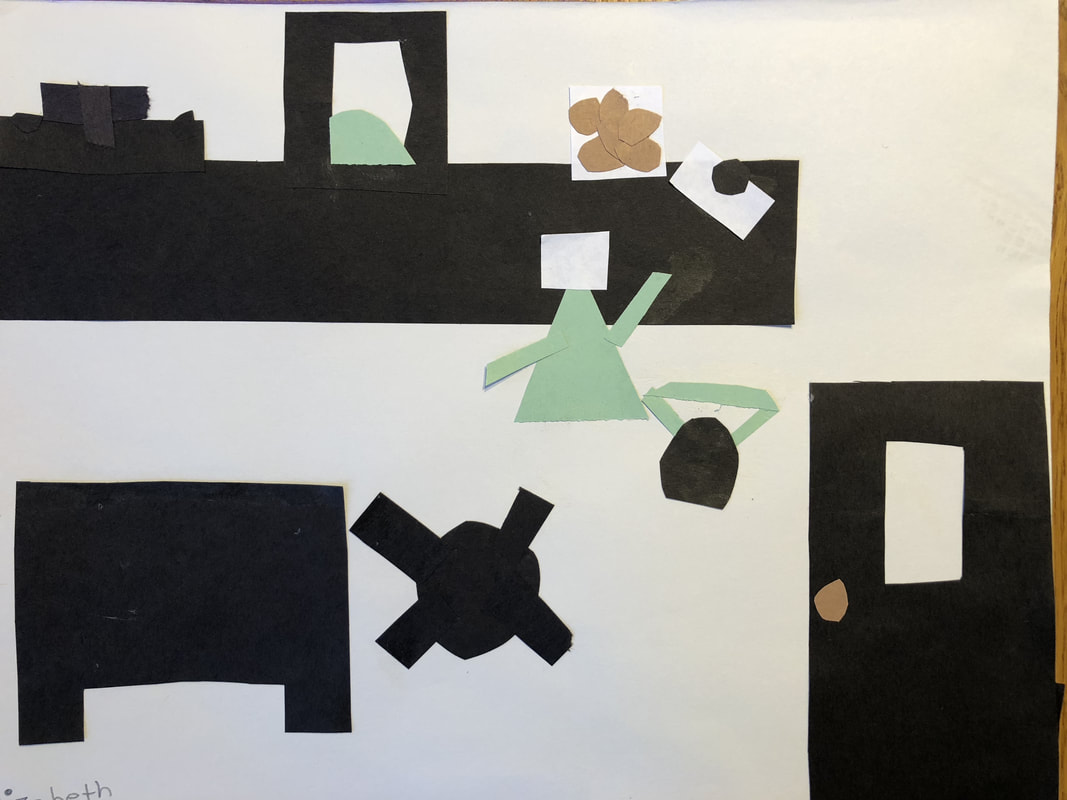

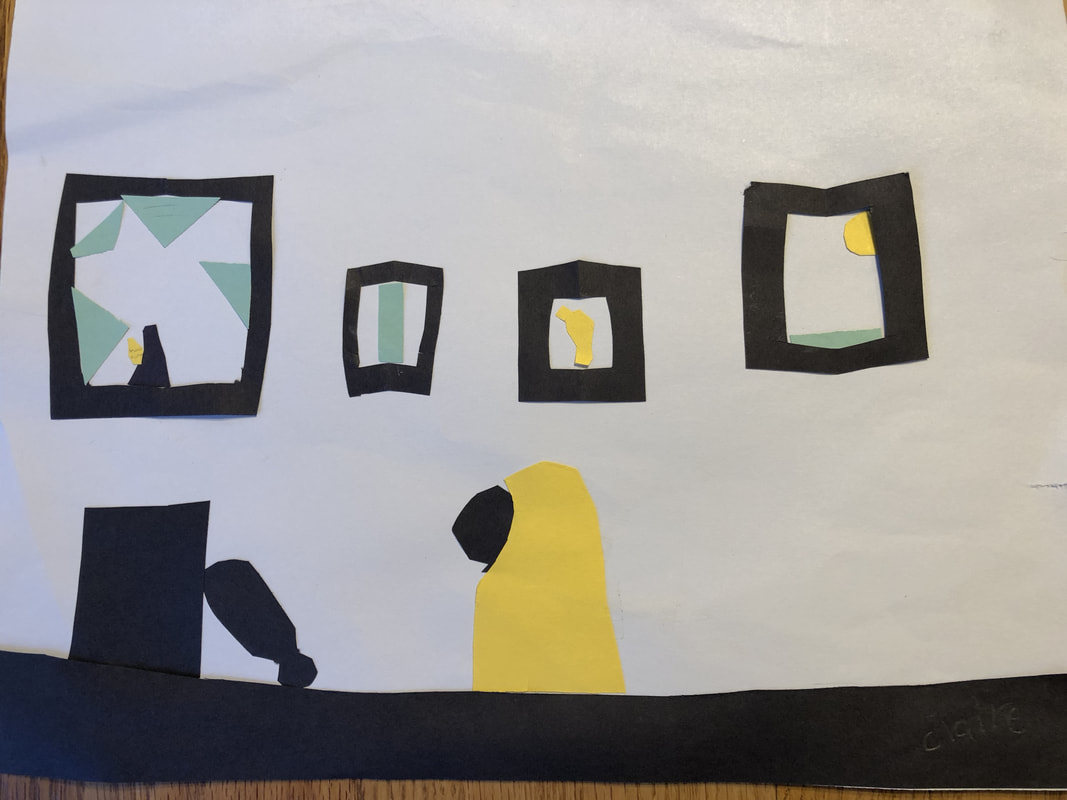

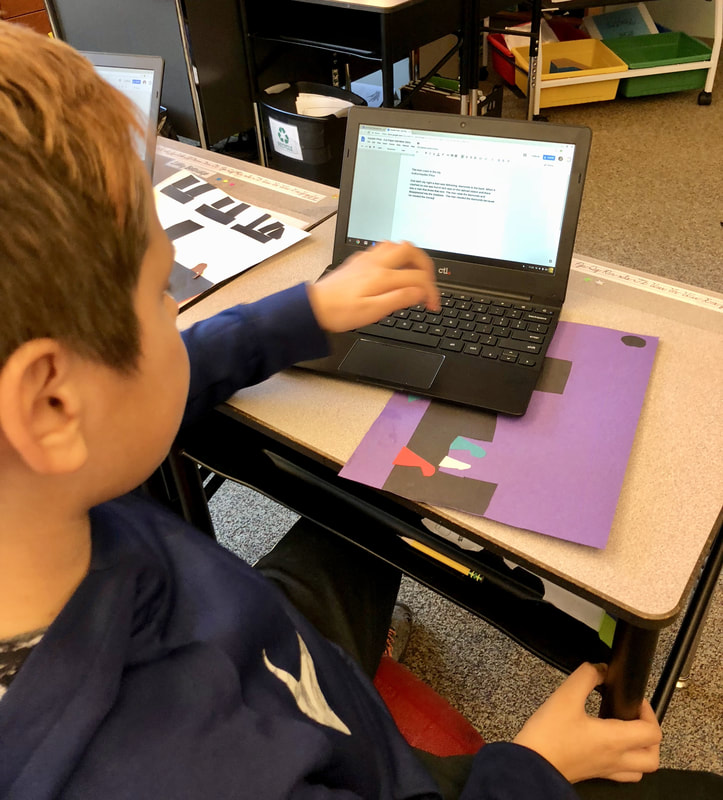

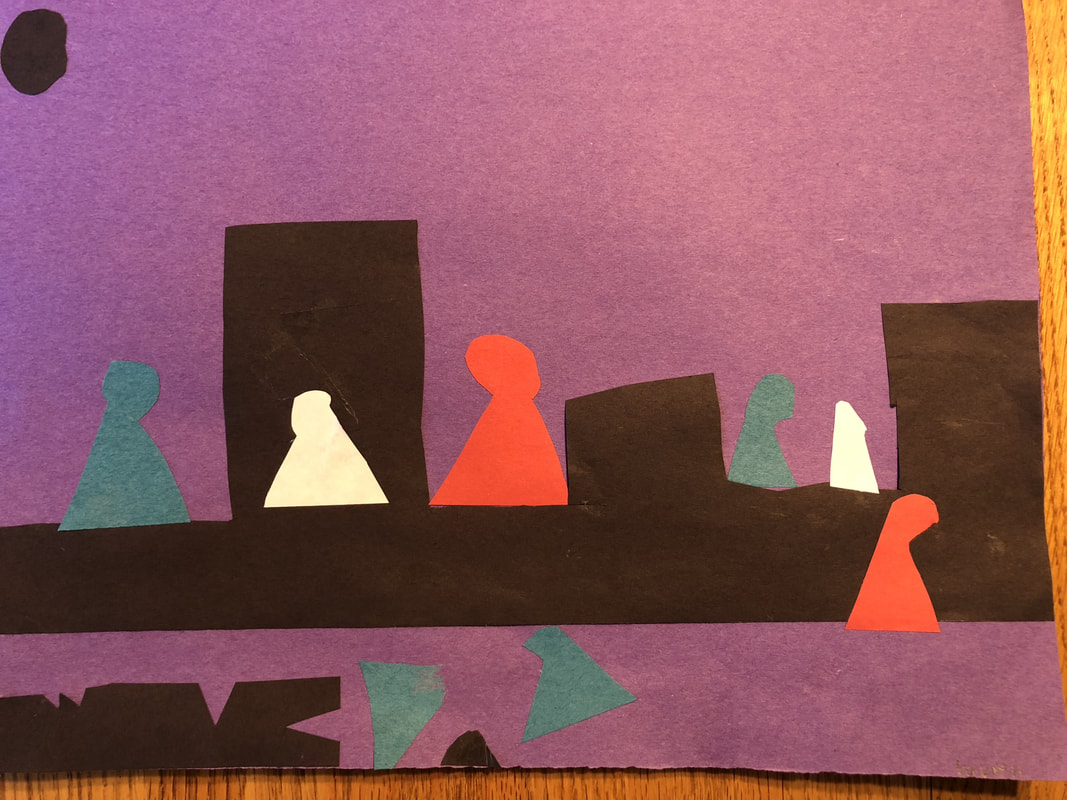

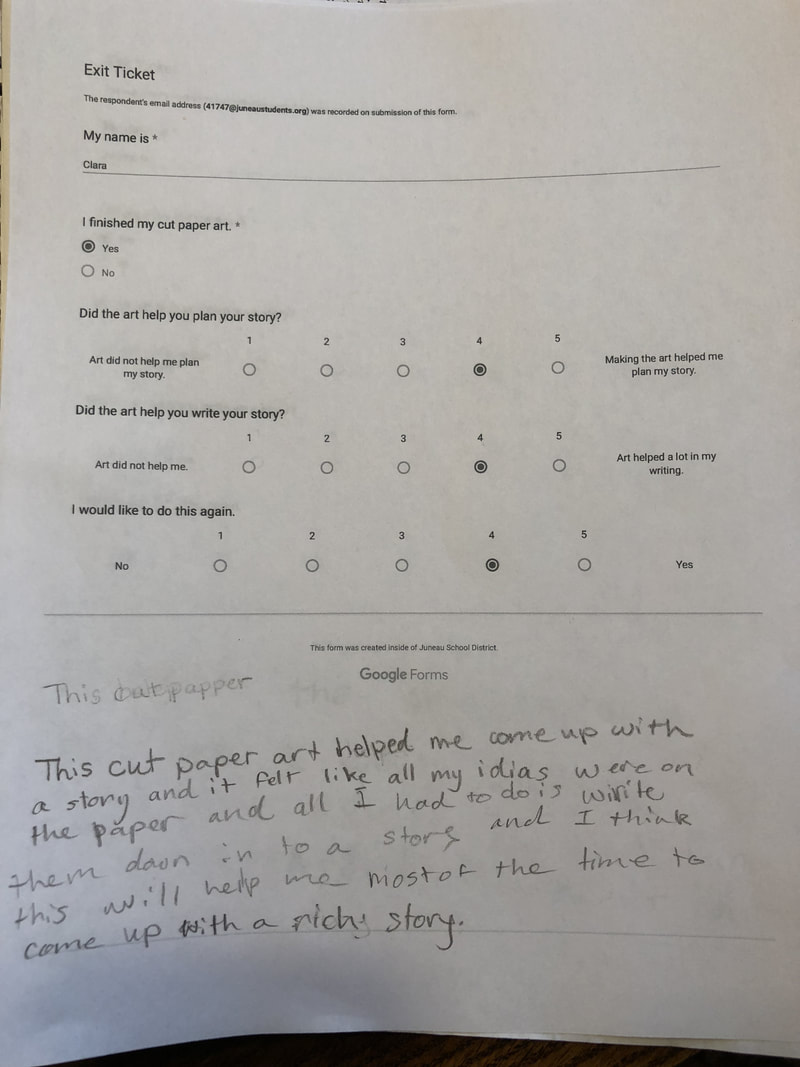

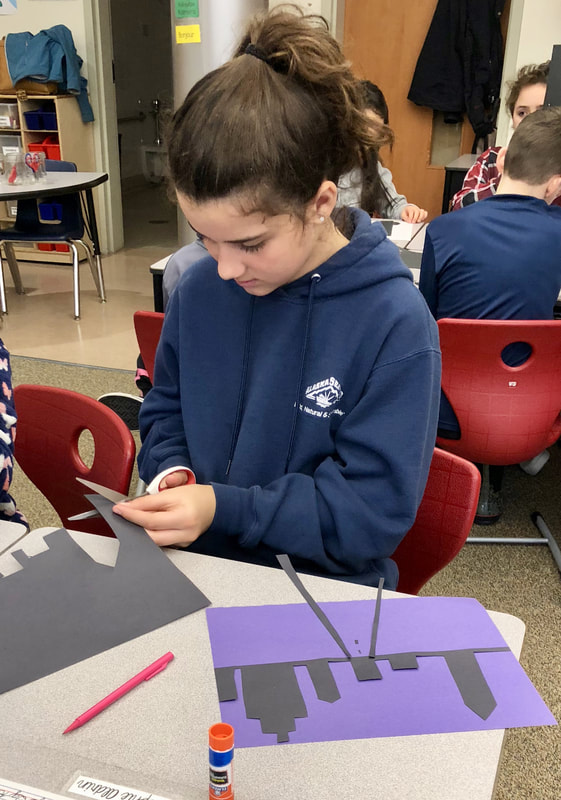

by Nadine Marx 4th Grade, Auke Bay Elementary Too often I see a blank stare on my students’ faces when they are tasked with writing. The pressure of an assignment empties their brains of ideas and they don’t know how to start. After participating in Jamin Carter’s workshop, Cut Paper: A Pathway to Creative Writing, I was excited to try his way of warming up students by integrating art into the writing process. Students would learn about art elements (shape, size, color, space) and create a piece of art using construction paper, scissors, and glue, and in doing so, would plan the setting, characters, and problem in a story before being asked to write a well-developed narrative. Before teaching Jamin’s lesson, I led students through mini-lessons on story structure, problem and solution, figurative language, and how to write and punctuate dialogue. Then, over two days, I taught Jamin’s lessons as scripted in the materials provided at the workshop. Students enjoyed learning the gestures that went along with the art elements. They loved playing Pass the Setting, and were excited that they would create their own picture of a problem that they would write about. On Day 3, I was surprised (and delighted) that most students had no problem thinking of a problem to illustrate, and were able to get right to creating a picture. One student needed some time to think of a problem, but then easily finished his picture within the time given. Students were asked to create a paper scene of the problem, or the middle of their story, showing setting, time of day, characters, and lastly, give a hint as to how the problem might be solved. On Day 4, students got started with their narrative writing. I was clear about my expectations, showing them a scoring guide I would use to evaluate their writing (thinkSRSD.com). Because of increasing expectations for 4th graders to type responses on assessments, I provided a google doc for students’ writing. Three of 23 students opted to write their story in their journals, while the others typed. When students had their first draft of their story done, I asked them to complete an “Exit Ticket” on Google Forms about the project. I asked if they finished their art, if the art helped them plan their story, if the art helped them write their story, and if they would like to do this again. Questions 2-4 were answerable on a scale of 1 to 5, 1 being on the No end, and 5 meaning Yes. Offering these choices may have been a mistake, since students gave a lot of 3s, making data less telling. After reviewing answers, I printed the individual forms, allowing space at the bottom for a written explanation of their answer. This was more helpful. But because I was asking students for multiple edits and rewrites, most written comments were harping on the amount of work this project was. Apparently they did not like to edit. A few written comments expressed the students’ enjoyment of the project. My own observational data led me to believe that creating the picture of the problem before writing the story was highly effective. Students had created the setting, characters, and problem and had thought about the solution before starting to write. I thought that students seemed to be writing their stories more quickly, and just as I had felt that the story flowed out of my pen after having done most of the thinking and planning beforehand during the workshop, I thought that students’ writing seemed to be an easier process for them. I did not see students staring blankly at the screen or page, and if they were, it was because they were trying to think about how to satisfy the expectations of the scoring guide. Would I do this again? Absolutely! It did take a good bit of class time to teach the art concepts and go through practice to get them ready for their part. My class worked on this during the last week of March, and had we done this earlier in the school year, we could have had more opportunities to create additional cut paper stories and write them. At this late date, we had to finish assessments and complete the last of our 4th grade tasks. Next year, I would teach this in August or September, and use the strategy several times throughout the year, making the time invested in the background knowledge more useful. Trapped! By creating art, and thinking about art elements of shape, size, space, and color, students planned the setting, characters, problem and solution for their narrative stories while engaged in creating with paper, scissors, and glue. They planned setting while choosing a background color to represent day or night, or interior lighting. They cut out trees or furniture or buildings and further developed their setting. They thought about character development while shaping their characters, choosing colors and shapes that would represent who their characters where and how they would interact. They added shapes to represent the problem of a broken vase, a cookie jar that was out of reach, a train that crashed or stolen jewels. Then they developed a visual clue of how their problem could be solved. While working on their art, students talked with their table groups about the process, and got more ideas, and explained to each other what each part meant. When it was time to write, their stories were written in their minds, and they only needed to get them out in words. Often teachers ask students to write and then give them time to create visual art as a reward for getting their work done. This now seems backward to me. Having intentionally created art with a meaningful setting, characters, and plot, students were more than ready to write.

By John Wade 7th Grade ELA, Floyd Dryden Middle School by Michaela Moore JDHS, ELA & Drama To introduce the play, Death of a Salesman by Arthur Miller, I first put an image from a poster of the play on the overhead and had the students go through the Thinking Routine of SEE/THINK/WONDER:

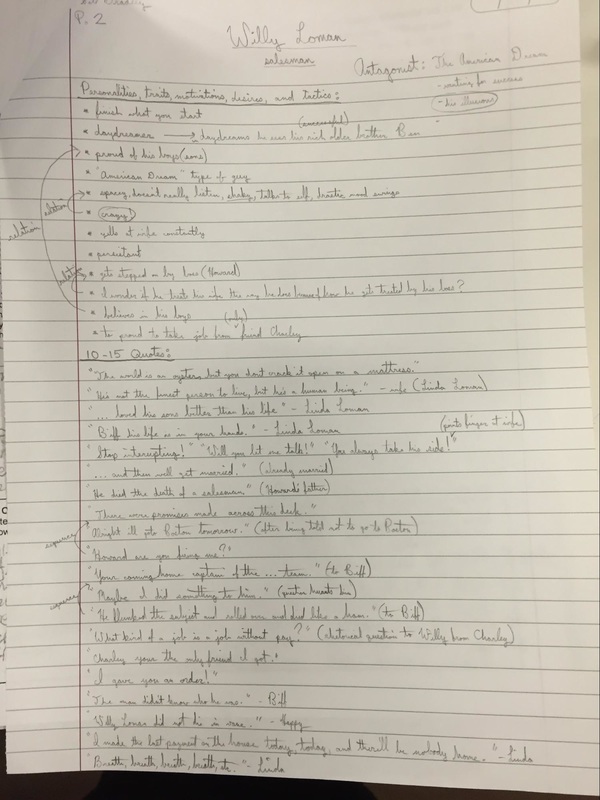

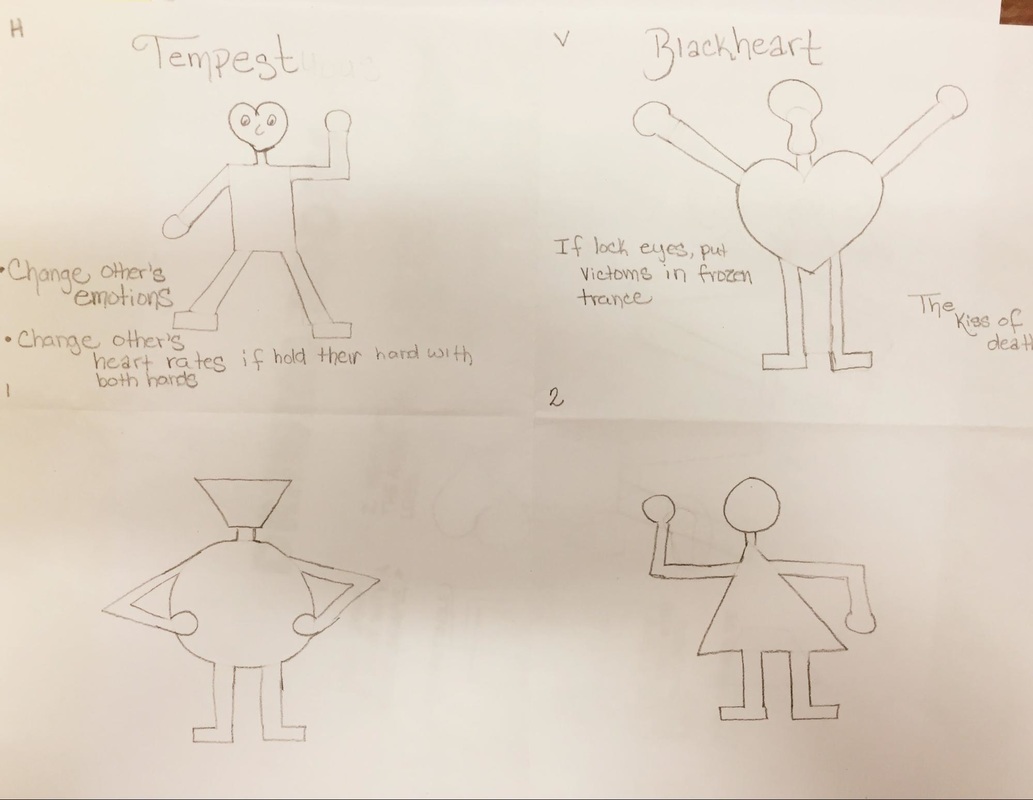

After this Thinking Routine, I asked the students to complete a Crowdsourcing activity about Arthur Miller. The students found information quickly about Arthur Miller and came up and wrote in a word splash on the whiteboard fun and important facts. We took a few moments to discuss surprises and interesting facts found in table groups and in whole group. Then I asked the students to prepare for notes: I introduced the 4 main characters from Death of a Salesman to students and asked them to choose one character that they would focus on in their project and notes. I instructed the students to write anything important down about the character (personality, weaknesses, strengths, choices, goals, motivations, etc) while we watched the play. After we finished watching and discussing the play, I passed out the text of the play and asked the students to fill in holes in their notes about their characters AND to add important quotes said by their characters, or important quotes others said about their characters. Once, these notes were complete, I taught the students step by step how to draw a caricature of their character beginning with a sketch first and then moving into their final draft. We first discussed the idea of caricatures and how they were different from real portraits or pictures. We discussed the symbolic nature of caricatures. (Learned from work of Richard Jenkins).

2. Show the students how to draw a caricature from lines, shapes, and patterns and have them draw your example, and have them rough draft sketch out a caricature of their Death of a Salesman chosen character. 3. Show the students how to turn their sketch into a real caricature of their chosen character. 4. I showed the students how to do Richard Jenkins’ inking technique (using sharpie to outline your pencil drawing) and then coloring technique (how to use colored pencils to get different shades and different textures) and shared with the students Richard Jenkins’ helpful handouts on hair and faces.

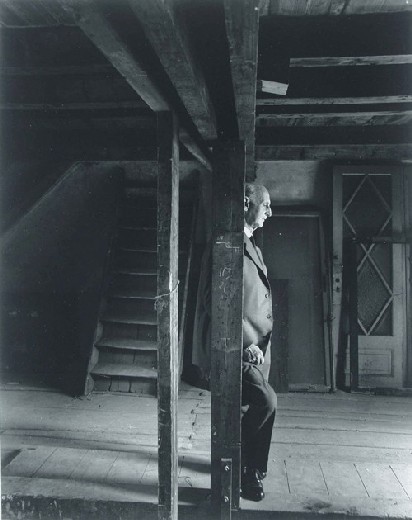

by Tracy Goldsmith Dzantik'i Heeni Middle School My 8th grade Language Arts class students studied the Holocaust. They were assigned different Holocaust novels to read and they participated in literature circles using those novels. We started the unit by using the Step Inside Artful Thinking Routine with this image; This is an image of Otto Frank, on the opening day of the Anne Frank House as a museum in Amsterdam. I asked students to stand up and quietly place themselves into the same position as the person in this portrait. While they quietly, stood in position looking at the image, I asked them to image what this person might be thinking or feeling. I wanted them to come up with a story about this picture and this man. They stood silently for one minute and then they had to write a journal entry answering the same questions. Some student responses are below:

The unit involved many different activities related to the Holocaust. One resource we used extensively was the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum website (www.ushmm.org). To extend the Artful Thinking routine of “Step Inside,” the students were assigned a portrait and first person narrative project. They started by finding one victim or survivor whose story they wanted to explore more on the USHMM website. There is a link on the website that shows ID cards with pictures and information about victims and survivors. After finding a person that they wanted to study more, students had to read the information about them and then turn that into a first person narrative. This first person narrative would be read out loud to the class later in the unit. The activity of writing in first person really stretched their understanding of what an individual was experiencing during the Holocaust. Being able to read it out loud to an audience, made that story come alive. Many students were emotionally touched by the narrative readings.

|

ArtStoriesA collection of JSD teachers' arts integration classroom experiences Categories

All

|

|

|

Artful Teaching is a collaborative project of the Juneau School District, University of Alaska Southeast, and the Juneau Arts and Humanities Council.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed