|

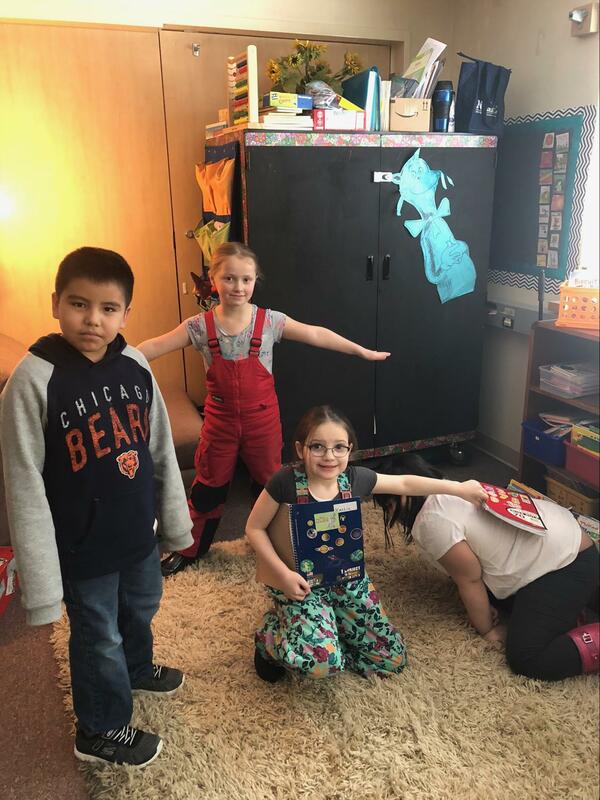

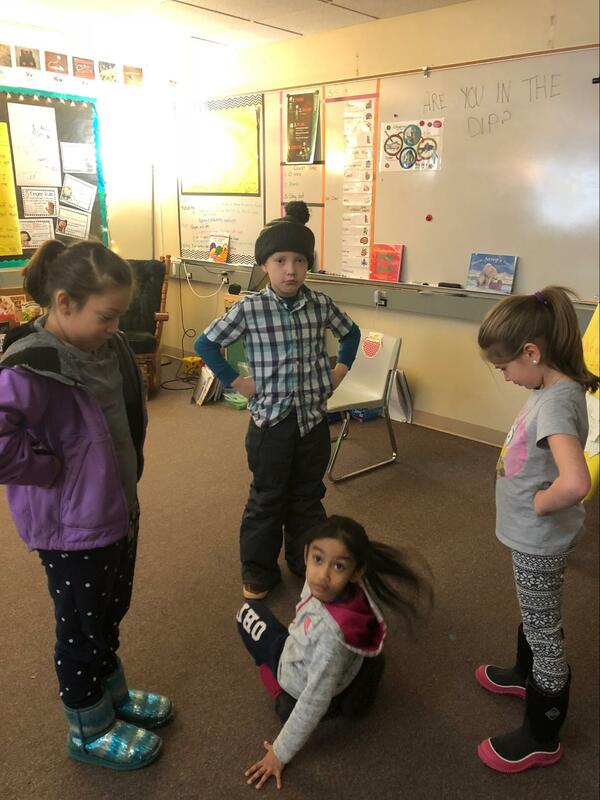

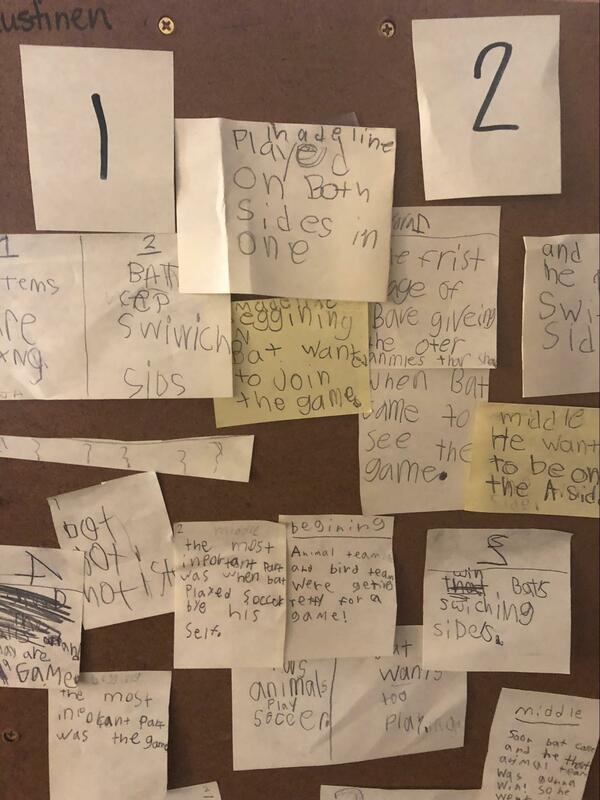

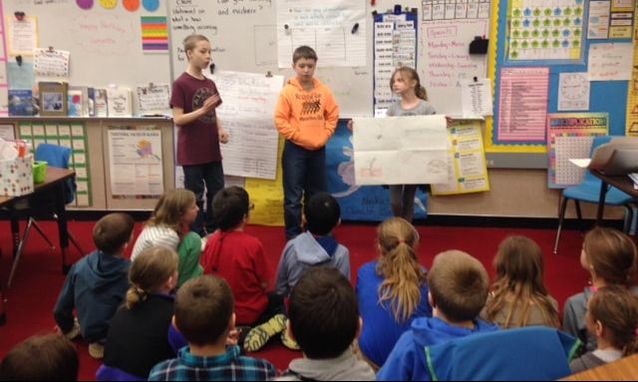

by Shawna Puustinen Primary multiage, Riverbend School Artful Teaching has giving me so much to think about. I have spent the last decade integrating art into my language arts, science and social studies units. An art project here, a drawing there, a model of a neighborhood made out of milk cartons. That’s art, right? I guess it never occurred to me that I could use art to teach social studies, math, science and language arts. I would love to say that this realization resulted in a complete overhaul of my teaching, in which every lesson was embedded with artful learning. Of course, I can’t say that. I can say that I have embedded artful learning routines into my day (well, not everyday). I am slowly but surely building my understanding and gaining the skills needed to be an artful teacher. Our school has adopted the One School, One Book initiative. For the past two years our amazing PTO has picked one book and purchased a copy for every student, staff and employee in our building. The idea being that we will all read the book and be able to talk about it. Teachers read the book in their classrooms, students take their copies home and the school hosts some school community events and activities. This year, Arctic Aesop’s Fables by Susi Fowler was the book chosen. Each classroom picked one of the fables from the book to design a bulletin board. What started out as a small cooperative art project ballooned into a full-fledged unit of study. We looked at characters, settings, problems, solutions, and the moral of each story. We then compared the two stories, looking for similarities and differences. We had lots of great discussion about friendship and good sportsmanship. On what I thought was going to be the last day before I was to leave on vacation, the students worked together in small groups to create tableaus for their favorite parts from one of the two stories.

On Monday I boarded a plane for a wonderful week in the Florida sun, completely forgetting that months before I had promised the kids that we would do a puppet show. Guess who didn’t forget. My daughter, who just happens to be one of my second graders this year. Ugh! Aren’t there rules about having your own kids in your class? Just kidding. It has been a blast having my daughter in my class. So, that’s how it happened. I got back from vacation and my daughter reminded me and the rest of our class that I had promised a puppet show. Clay, sticks and imagination… I am going to start this section by confessing that I hate puppetry. Nothing makes me feel sillier than interacting with a puppet. I have tried...really. I have spent countless uncomfortable minutes having conversations with Impulsive Puppy and Slow Down Snail. It always leaves me feeling...weird. So, I knew that trying to teach a puppetry unit was going to stretch me in many ways. I started the unit with dot sticker popsicle stick puppets. The kids each got to draw eyes and mouth on their dot sticker and put it on a tongue depressor. Most of the kids were pretty excited, but a few were less than excited to be holding a tongue depressor puppet (oh, how I could relate to them). With great enthusiasm, I demonstrated arm positioning, puppet posture, large puppet movements (walking, running, going up and down stairs, lying down, getting up, etc), wrist movements (yes/no, looking up/down/around, reading, etc.), puppet emotions, and voice projection. The same few less-than-excited puppeteers actively tried to sabotage our puppetry lessons. Their poor tongue dispenser puppets experienced great head trauma while being repeatedly banged against tables and the floor. They refused to participate in voicing activities and their “I am too cool for this” attitudes were starting to spread. I was ready to call it.

As soon as the popsicle sticks were attached the kids were becoming their puppets. A few kids, were working together creating quick puppet skits. I still had one very reluctant artist. He was about as excited about creating his puppet as he had been about using a puppet. The kids got to pick one puppet to leave at school for the puppet show, and then take the other puppet home. One girl came back the next week with more than 10 little clay creatures she had made at home. It was neat to see how her creatures evolved from simple to very detailed and sophisticated.

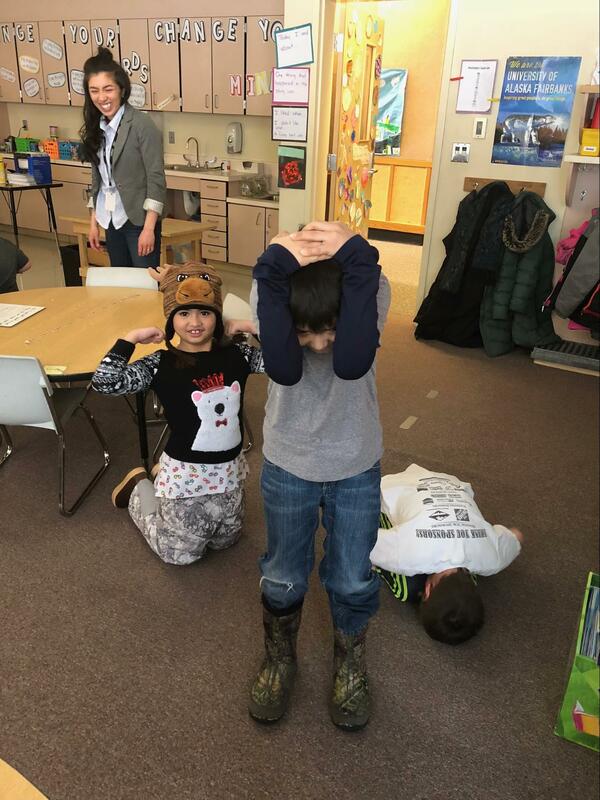

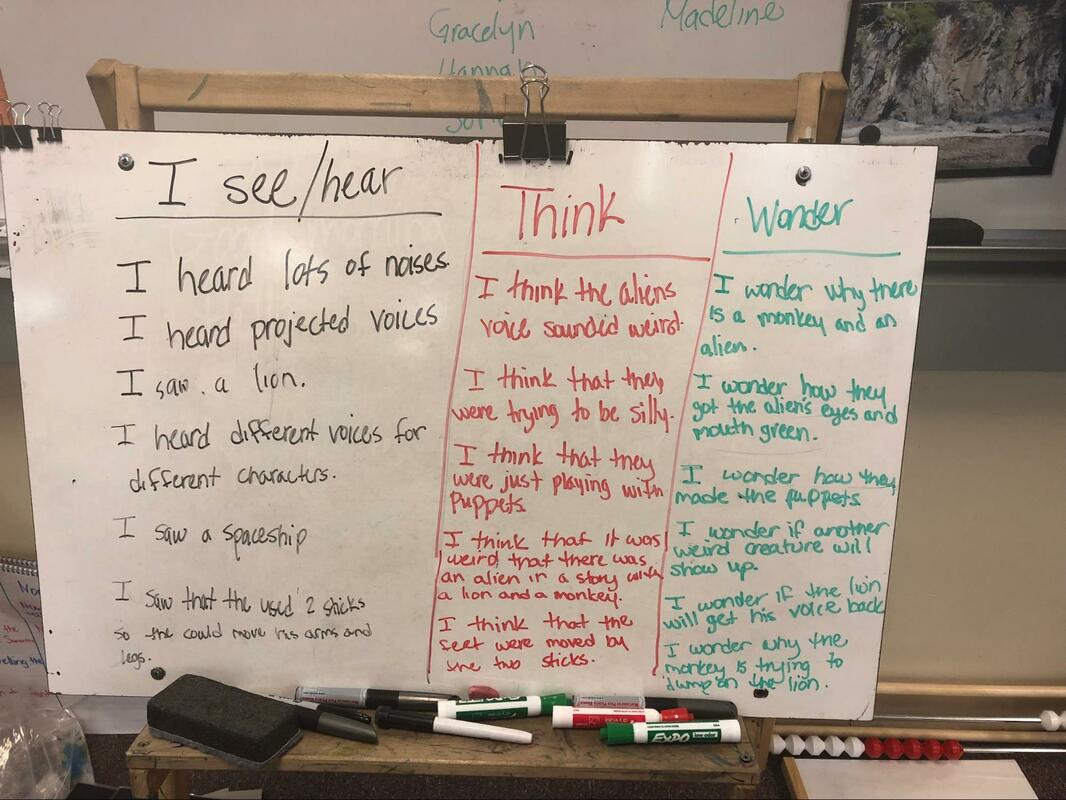

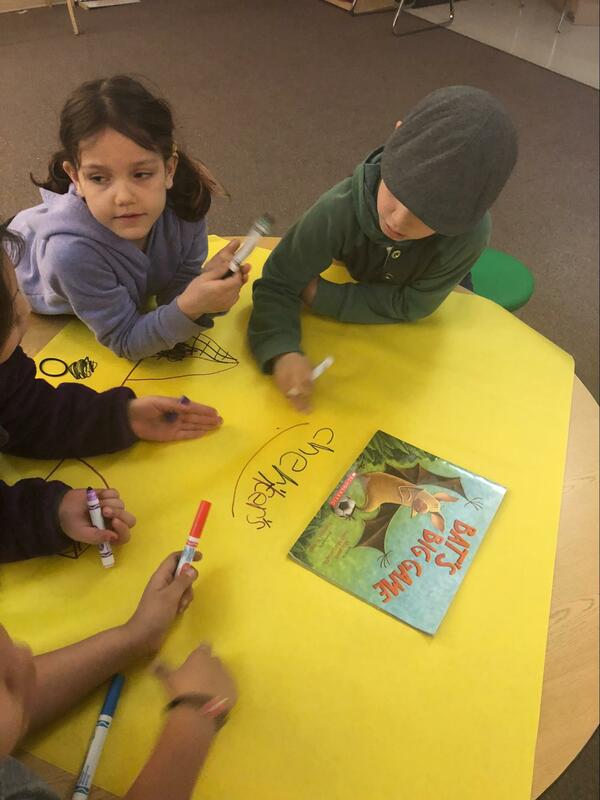

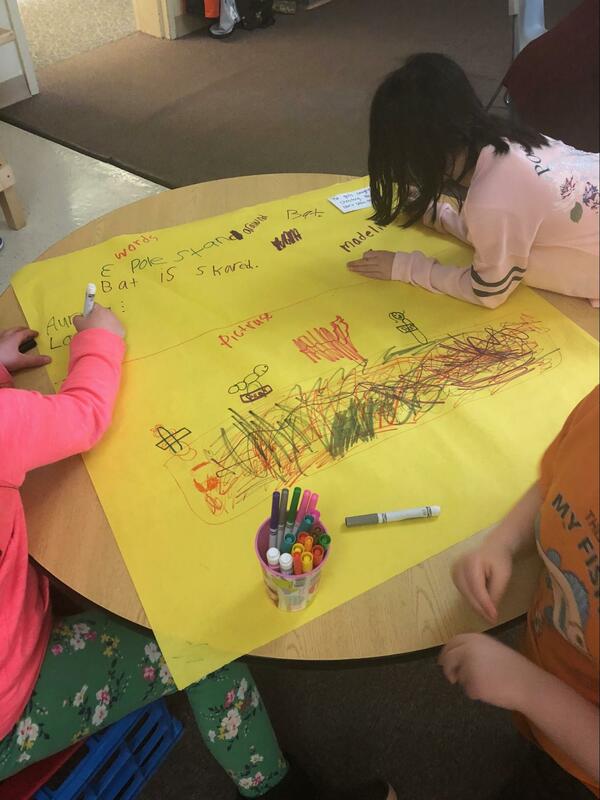

During a morning meeting time, we watched two videos of people putting on shadow puppet plays. After watching the videos, I used the “See, Think, Wonder” thinking routine to help my kids process what they had seen. I was very impressed with what they observed. Many picked up on the techniques the actors were using to make their characters come to life. They noticed things like how voices changed from one character to the next. How the puppeteers used multiple sticks to move different parts of the puppets. They noticed the props changed from one scene to the next. They wondered about what would happen next in the stories and how the puppeteers made their puppets. As I watched and listened to them share with each other, I saw engagement, inclusion, success. The playing field was level. Each one of them, regardless to their background, learning needs, age, grade, etc., was able to share something that they saw or thought or wondered. Since the tableau process is very familiar to my students, I used the same process to get them started with planning their puppet skits. The groups did their thinking and sharing just like in tableau. When they were ready to plan, I had them go to tables to brainstorm what they would need to make their scenes works:

Tomorrow is our big production. The kids haven’t even finished the scripts, but I think it will be okay. I told them that I would video each of their skits and then we could all watch them together on the big screen in the room. All but one seemed really excited about this. As I am sitting here writing this, I can’t help but smile. These kids have done some amazing work in the past few weeks. It goes way beyond close reads, reading comprehension and craft projects. They connected to a story, stripped it to its bare bones, extracted the underlying message and then rewrote it in their own words. They worked cooperatively in groups. They explored new and old art forms. They created. They problem solved. They observed. They asked questions and found answers. They supported one another. They tried new things. They took risks. They stepped outside of their comfort zones. They failed. They persevered. It would be hard not to be proud of the work they have done. So tomorrow, no matter what happens, I will stand and applaud each of them with genuine admiration.

And it all started with one fable, from one book.

0 Comments

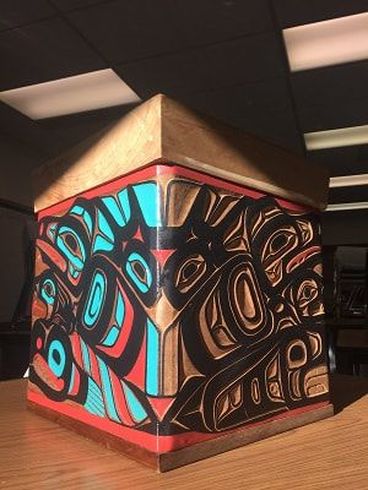

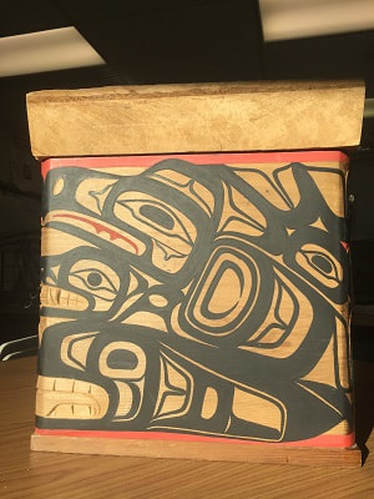

by Tennie Bentz Dzantik'i Heeni Middle School, 7/8th grade Bentwood Box created by Leroy Hughes Eighteen primarily Alaska Native students enter the classroom full of energy on this fall afternoon. Most of them struggle in math and it is the last class of the day, so no one is ready to buckle down to learn about measurement, surface area, volume, symmetry, or ratios and proportions. Then Ruby Hughes, our Cultural Specialist, brings in the most beautiful Bentwood Box any of us have ever seen. It is large, approximately 24 inches on each side. Intricate formline designs are carved on two sides and painted on the other two. The students settle down a bit and I start to hear sounds of excitement as they begin to look at and touch the box. They are hooked. Not only are they in the presence of a masterpiece, they are about to create their own. Students settle into their seats with the Bentwood box at the center of the room. We begin the I See, I Think, I Wonder thinking routine and discuss what students see when they look at the box. What makes this box so beautiful? Is it the size, the shapes, the colors, the symmetry? Groups look closely at the box and explain how they think the box was built. Some of our students have built one before so they can help explain the process to others. Many students wonder how they will ever be able to complete something so complicated. Step by step, we tell them. It’s going to be a long process, but in the end they will have a tangible item that they will be able to give as a gift or keep as a memory of the challenge to come. A couple of days later, Ruby brings each student their own rectangular piece of yellow cedar from Hoonah. Sealaska Heritage Foundation helped cover the cost of the cedar which is fairly expensive. Ruby explains the importance of precise measurement and we show students examples of boxes that were square and others that are not. Students see the beauty in symmetry. Perfectly bent corners, straight lines, tops proportional to the bottoms. Armed with a ruler, pencil and their new knowledge of measurement, students begin measuring precisely to ¼ and ⅛ and even 1/16 of an inch. Some of the students fly along, making their measurements while others fall behind. One girl starts to wander about the classroom bothering others. At first she won’t tell me why she is wandering and then I realize, she doesn’t know how to read her ruler. She’s never been asked to measure something so precisely, especially when mis-measuring by something as small as ⅛ of an inch will end up creating a box that is no longer symmetrical and square. This young lady would rather give up than end up with a less than perfect product. I convince her to sit back down and together we began to measure. We create a template because remembering which line is which on the ruler is too difficult for her on this day. Soon she has her measurements complete, her corner angles drawn correctly and the rest of the class finishes soon after. The project flies by. Day after day as students saw, sand, and chisel their way towards a final project. Ruby works patiently guiding half of the students through the process of building their boxes. I work with the other half of the class tying in the math behind the art. We learn about surface area by creating wrapping paper and volume by filling the example boxes with cubes. Fractional measurements are converted to decimals and percents. Standard systems of measurement are converted to metric. On and on the math goes with students always excited to stop with the math so they can just go work on the art. Soon the boxes take shape. Ray Watkins visits Dzantik’i Heeni and he and Ruby take a few kids at a time downstairs to steam and bend the boxes into their square shape.The other students wait impatiently with me. They want to see if all of their precise measurements and persistence sawing and chiseling have paid off. Will their final product have the lines of symmetry and the perfect bends in the corners? Soon students begin to carry the boxes back upstairs, smiles on their faces. Most of the boxes are nearly perfect, a few aren’t quite square but Ruby is sure that she and Ray can magically fix them overnight. The next day, when the students return, everyone has a perfect box. Soon the students began new measurements to create perfectly fitting bottoms and proportional tops. The boxes were nearing completion for many students. The experience of building their own Bentwood box was enough. Others however wanted to take the box further and create their own formline design to put on the outside. We spent some time looking at the Colors, Shapes and Lines on the masterpiece Bentwood Box that had served as our inspiration through this entire process. The colors were few but bold. Red, black, teal and natural wood. Ruby taught us the names and relationships between the shapes. Ovoids serve as the center from which U-shapes extend. We learned that the shapes rarely stand on their own, but connect and flow from one form to another. To me this was the perfect analogy for how math should be taught. Fractions should not stand on their own, there needs to be flow, a relationship and connection between the math and real life application. This was the perfect opportunity to teach ratios, proportions, similar and congruent figures and lines of symmetry through art. Ruby taught the students how to make ovoids using lines of symmetry and I created an activity where they had to measure the height and width of the ovoids and then create new ovoids that were similar using ratios and proportions. Most of the students ended up with a set of ovoids that they could use as a template when creating the formline design on their boxes. Some students quickly realized that they could avoid the math and just draw ovoids within ovoids to create their template. Whichever method students chose to use, the concept behind math supporting art was cemented. Students are still working on their formline designs. One young lady is trying to get in touch with her grandparents to learn more about her lineage so she can put the correct clan crests on her box. She is an inspiration to me and reinforces the need for more projects like this one. She doesn’t do much in math class and did very little of the work when we worked with the math behind the art. Some may call this a failure of the project when looking at it from a math perspective but this student is so proud of the masterpiece that she created that she is taking the time to make sure the connection to her family’s history is accurate. She plans to give her box to her grandmother in Angoon. That in itself proves the project was successful in my eyes. Acknowledgments:

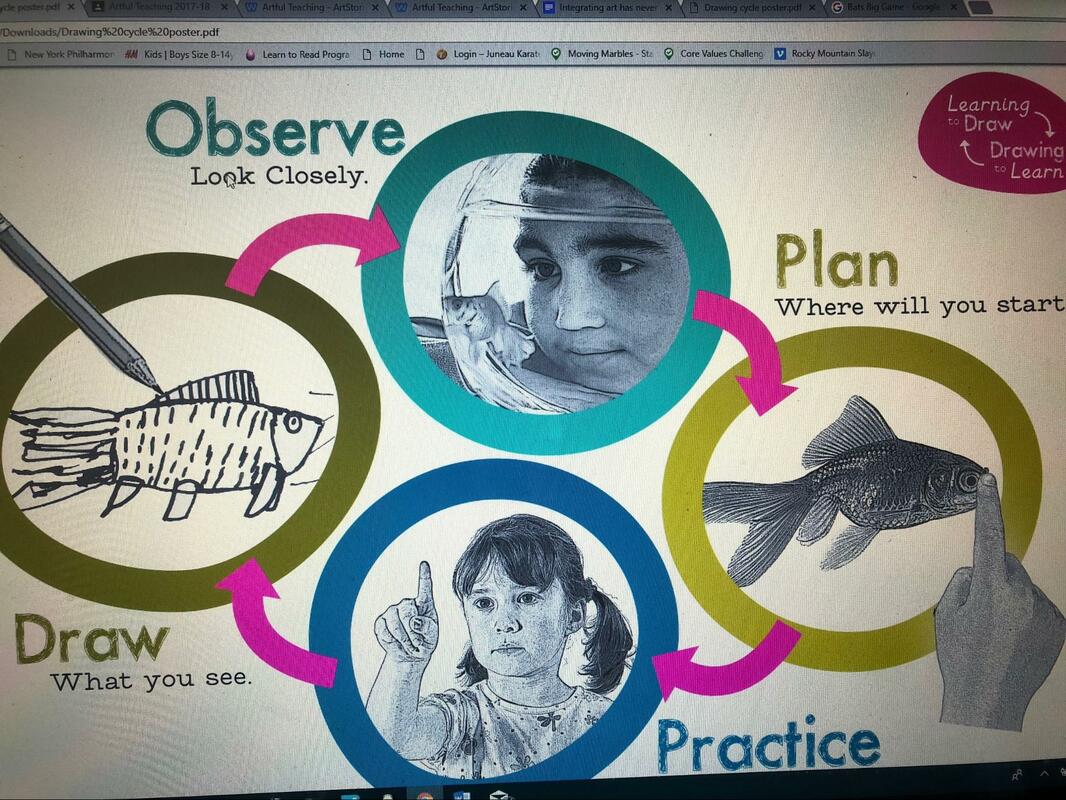

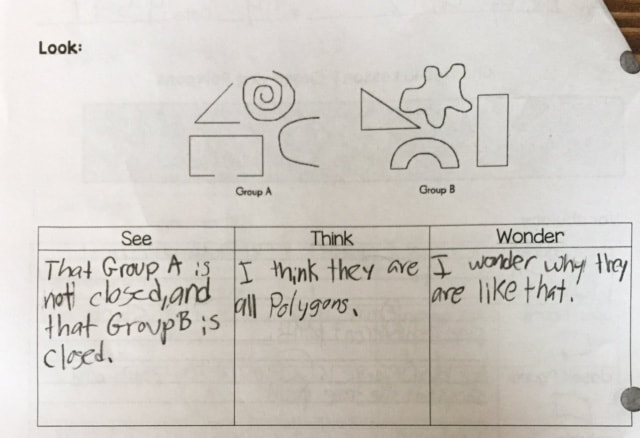

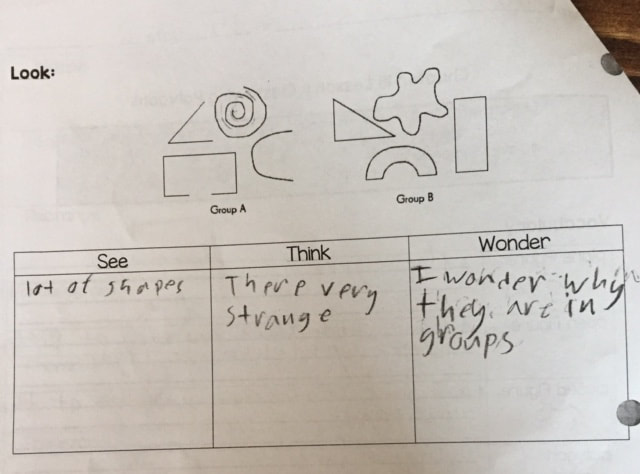

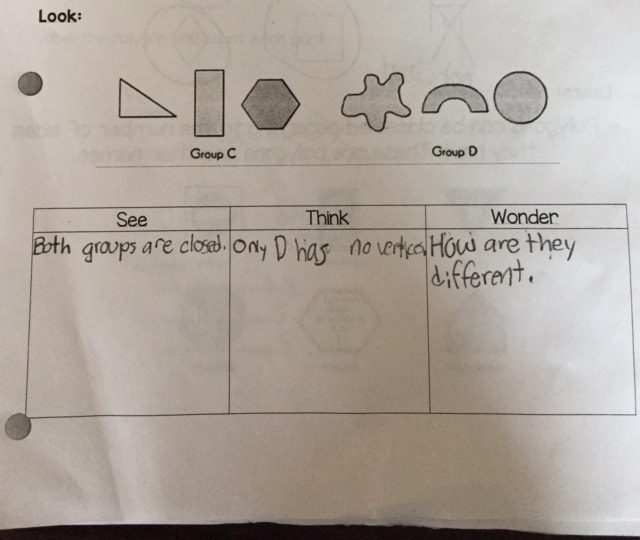

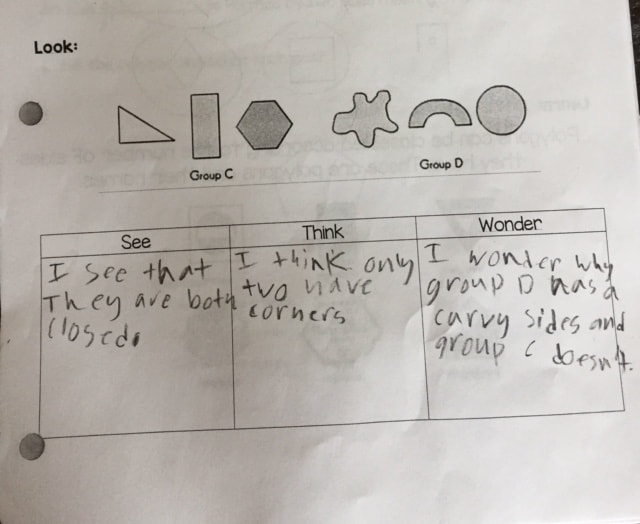

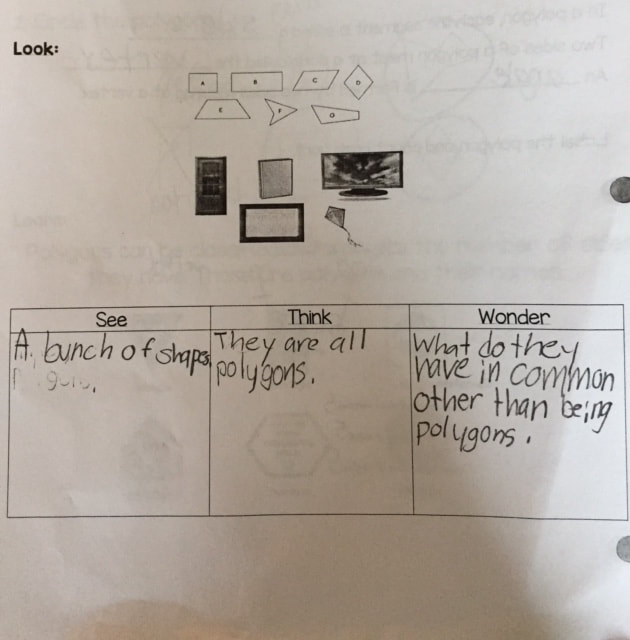

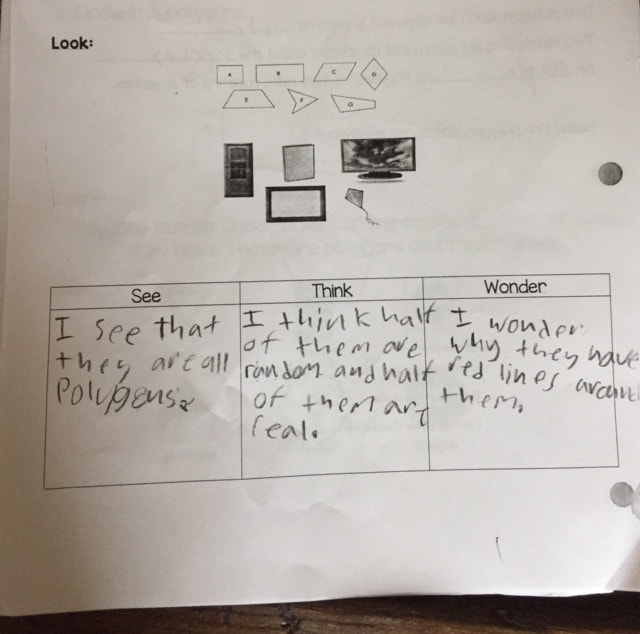

I owe a huge thank you to Ruby Hughes. Her calm presence and patience was an inspiration through this process. Without Ruby’s help and support, this project would have been a disaster. Ray Watkins’ help behind the scenes made this project streamlined and successful as well. Thank you to Sealaska Heritage Institute for your generous support providing the yellow cedar and to the Artful Teaching grant for purchasing colored pencils for the final box designs. By Marnita Coenraad 3rd Grade, Riverbend Elementary School As I began my Artful Teaching journey last year, I was excited to find how seamlessly I was able to integrate Artful Thinking routines into my literacy instruction. I found that Reading Portraits added depth of knowledge to our reading of biographies, and art seem to provide an entry point for struggling readers. This year that trend continued with our study of tableau. As I became more familiar with the routines, I branched out and used them in science and social studies as well. But even as I experimented with these new content areas, I found that bringing the routines into my math instruction was more challenging. I made it a goal for the spring semester to bring Artful Teaching to my math lessons. For each new math lesson, I create a guided notes sheet. These notes serve as guide through the lesson, as well as a reference that can use when completing their independent practice or homework. I decided that I would include a thinking routine at the beginning of each math lesson. I hoped that this would stimulate thoughtful discussions and promote student discovery of mathematical concepts. The following is an introduction to geometry lesson. I used the thinking routine “See, Think, Wonder” to help students discover characteristics of open/closed shapes, polygons, and special quadrilaterals. 1. Students started by looking at groups of open and closed shapes. I did not give them any indication as to why shapes were grouped in this way. Students then completed at least one entry for See, Think, and Wonder. I did not ask students to write in complete sentences for this exercise. You can see that students entered the lesson with varying degrees of prior knowledge. 2. After some direct instruction in open versus closed figures, students repeated the thinking routine with two more groups of figures. I was happy to see that immediately began experimenting with the new vocabulary introduced during the lesson. Again, some students were already familiar with geometry vocabulary, while others were engaging with it for the first time. 3. After direct instruction in naming polygons and their parts. We repeated “See, Think, Wonder” for a final time. Students again used the new vocabulary in their observations and inferences. Several students noticed that some of the shapes were line drawings, or “random” shapes, and some were “real,” meaning photographs. This breaking into two groups was an unexpected result of my having two groups in the previous two routines. I had hoped that students would notice they all had four sides. Although there were a few misconceptions along the way. I was happy that students were able to construct their own definitions for open shape, closed shape, and polygon. With help, we also discovered the characteristics of special quadrilaterals like rectangles, parallelograms, and trapezoids. I have taught similar geometry lessons that are vocabulary rich, and it can be difficult to get students to engage with the new words and their meanings. Teaching this lesson through the Artful Thinking routine encouraged students to construct their own definitions and provided a safe space to try out their new vocabulary terms. Since this lesson, we have used the art of Kandinsky and Mondrian to identify and name 2-dimensional figures. Students are highly motivated to find and share the shapes they see.

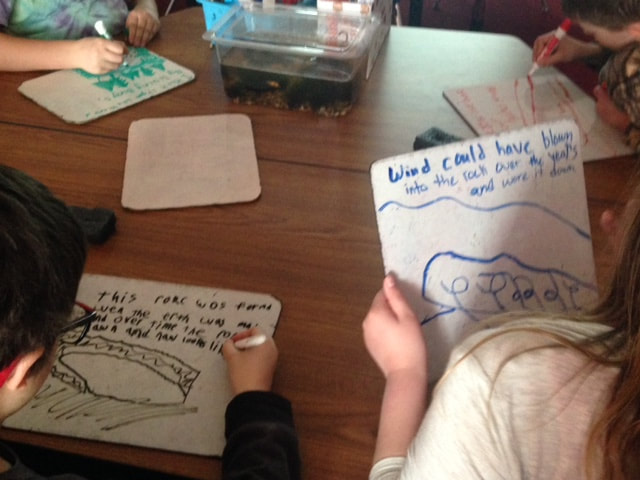

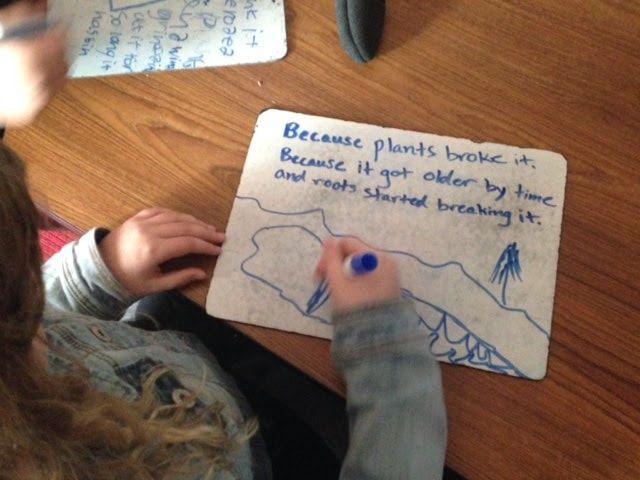

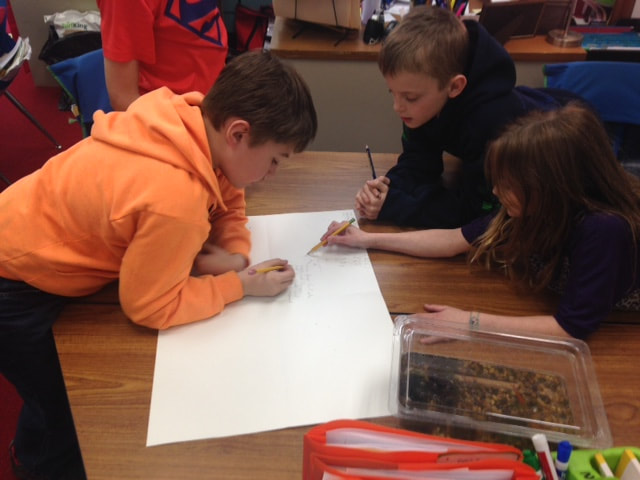

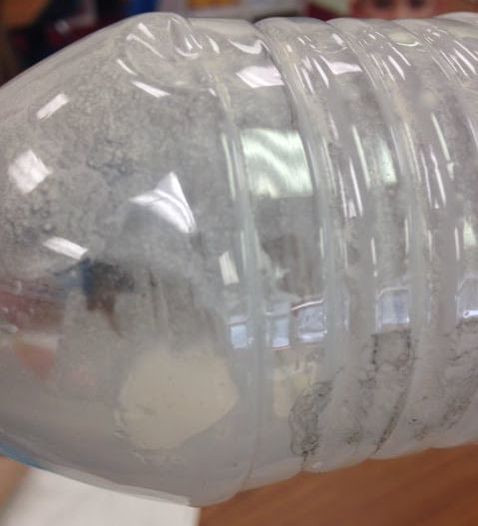

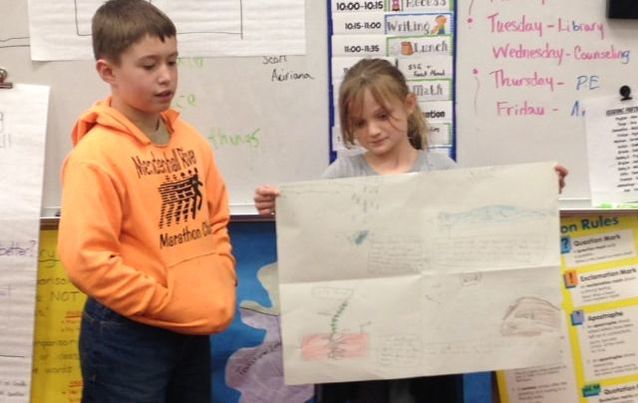

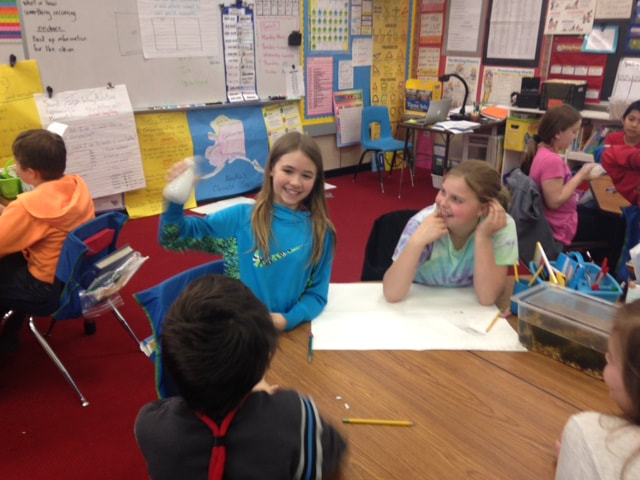

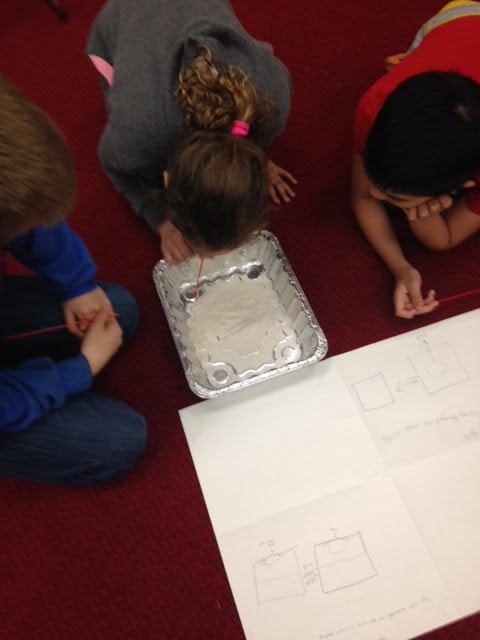

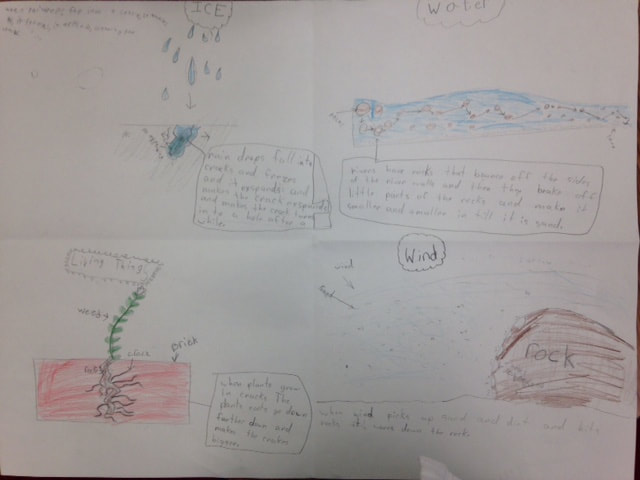

I am continuing to experiment with using art in my math instruction. I recently used Navajo blankets to review symmetry and introduce area. While arts integration in math does not come as naturally to me as in other subjects, I am enjoying the challenge. More importantly, I see students participating in class who are usually reticent to volunteer in math discussions. Since we teach art terms throughout elementary, I have found that students are comfortable analyzing and discussing art. The consistency of thinking routines coupled with the familiarity of art has made math more accessible and enjoyable for many of my students. By Jennifer Heidersdorf 4th Grade, Mendenhall River Community School Student Thinking about this image: What do you see? I see sand and mountains. I see an arch. I see a rocks and a canyon with a hole. I see sandstone, orange. I see a rock with a hole in it. What do you think? I think it’s a desert. I think it has reptiles. I think the sun is going down. I think there’s a cave. I think the picture was taken in Arizona. I think there’s very little water. I think it’s really old. I think the rock eroded What do you wonder? I wonder if it’s a hot place. I wonder if it’s a canyon. I wonder if the shrubs are grass and if the arch will fall. I wonder where this picture was taken. I wonder if sand made the hole. I wonder if things got fossilized in the rocks. I wonder if there’s a road or cactus there. I wonder what’s beyond the rock. I wonder how it was created. While attending the NSTA Conference this spring and learning with other teachers on how to implement the NGSS (Next Generation Science Standards), I got excited and thought, "wow, this sounds a lot like the Artful Thinking routine of See/Think/Wonder". We ultimately want all students to observe things, think about why things work, and ask questions that will hopefully lead them to future investigations to find the answers. Presenting students with a phenomenon in the form of pictures or other media creates an opportunity for students to look with their eyes wide open and share their ideas in a safe, nonjudgmental environment. This approach has become a common practice in the way that I start many of my lessons in my fourth grade class. For this opening science lesson, I wanted students to view a variety of images while doing a See/Think/Wonder routine. As we went through these slides, I had students respond aloud and also in written form. I didn’t frontload the lesson or give students any more information then that; my hope was that it would lead to them asking questions and that they would find a common occurrence among the pictures. Students were eager to share and had a wide range of responses and questions. When we finished looking at the images the first time, I asked them to take a quick look at the slides again and see if they noticed a common occurrence happening within the images. I love the engagement of students when they talk about what they’re seeing, thinking, and wondering. By separating out the questions, the routine stimulates curiosity and helps students reach for new connections. I could see from the student responses that they had a deeper interest. Student Thinking about this image: What do you see? I see sand and mountains in the background. I see a big hole in the the standing rock. I see a rock that looks like a hand without fingers. I see a statue of the illuminati. What do you think? I think it’s in the middle of nowhere. I think wind carved the rock. I think something hides or gets in the shade in the big rock. I think there’s water. I think it’s 10,000 years old. I think the rock is not stable and it might fall. What do you wonder? I wonder if people live there. I wonder if the rock is going to fall. I wonder if it was flooded and then got dried out. I wonder what’s behind the rock. I wonder if I can fit in the rock. I wonder if somebody sculpted the rock. I wonder where this is. I wonder how it came to be. Student Thinking about this image: What do you see? I see a cliff holding a building. I see the tide has gone down. I see what would be the ocean. I see wet rocks, seaweed, and blue sky. What do you think? I think it was hard to get down to the beach. I think they’re going to rebuild the house. I think it’s in a foreign country. I wonder if the person taking the picture is underwater. I think there was war before the house was built. I think people would go there on the 4th of July. What do you wonder? “I wonder where the photo was taken. I wonder if I’ve seen it before. I wonder if there was a tsunami. I wonder if the house was a church. I wonder if the water wore the cliff down. I wonder what the people are doing. I wonder how long the building has been there.” Engagement and Enthusiasm What I love is hearing students make connections and but having them make those connections on their own. I didn’t want to give students any vocabulary, I just restated what they said and eventually a student said the word erosion. At that point I asked him what he meant by that and then we were able to substitute that word with a definition that tied into what they were observing but they made the connection on their own. From this point we talked about the different forms of erosion and how it can cause change. Science activities that followed: These lessons served as an entry point into NGSS standards 4-ESS1-1 (Identify evidence from patterns in rock formations and fossils in rock layers for changes in a landscape over time to support an explanation for changes in a landscape over time) and ESS1.C (Local, regional, and global patterns of rock formations reveal changes over time due to earth forces, such as earthquakes). To engage students in the topic of weathering the next day, I presented the class with a picture of an interesting rock formation and gave them the following prompt: With your whiteboard, please use sentences, labels, and drawings to propose an explanation for how you think this rock might have been hollowed out. Please explain how you think this occurred using sentences and drawings. Our Four Investigations Wind: Student groups are provided a container of sand and a drinking straw. Students then blow gently across the sand with the straw. The students are able to see the changes in the sand surface and observe the moving sediment. Students must wear goggles when working with sand. Moving Water: Each group is given a water bottle half-full with water. They then place a piece of chalk in the water and take turns shaking the bottle (moving the water). The students stop after three minutes and make observations. Ice: Students look at a picture (or a real example) of a bottle that was filled with water and then frozen. They can observe the expanded ice sticking out from the top of the bottle and the overexpanded bottle. Living Things: Students are given a baggy with a cracker in it. The cracker represents a rock. Students use their fingers to “weather” the cracker Students then worked in groups of five to propose explanations on a large sheet of paper that had been folded into four sections. I walked from group to group and asked clarifying questions about the science content on the boards (“Can you be more explicit in your drawing about how you think this occurs?”) and about the students’ writing (“Can you label your drawings and add more details using scientific words to explain your drawings?”). I then explained that I wanted each group to come to the front of the classroom, one group at a time, to present their ideas. But, before the first group came up, I directed the students’ attention to a poster on the classroom wall that outlines the group sharing norms that the class developed earlier in the school year. The list contains items such as: • Examine each paper carefully for words and drawings. • Can you identify claims and evidence? • What questions can you ask? • How does your paper compare to other papers? As I reflect on these lessons, I see how important it is for my students to be able to explain their thinking with drawings and explanations. As students observed the connections that other students made, many had some realizations that their paper didn’t look anything like other students papers. I wanted students to have a range of connections but well thought out connections. This is something that students have to practice at, it definitely does not come easy. I plan to start this strategy much earlier in the year next year to see just how much students improve and grow through the year.

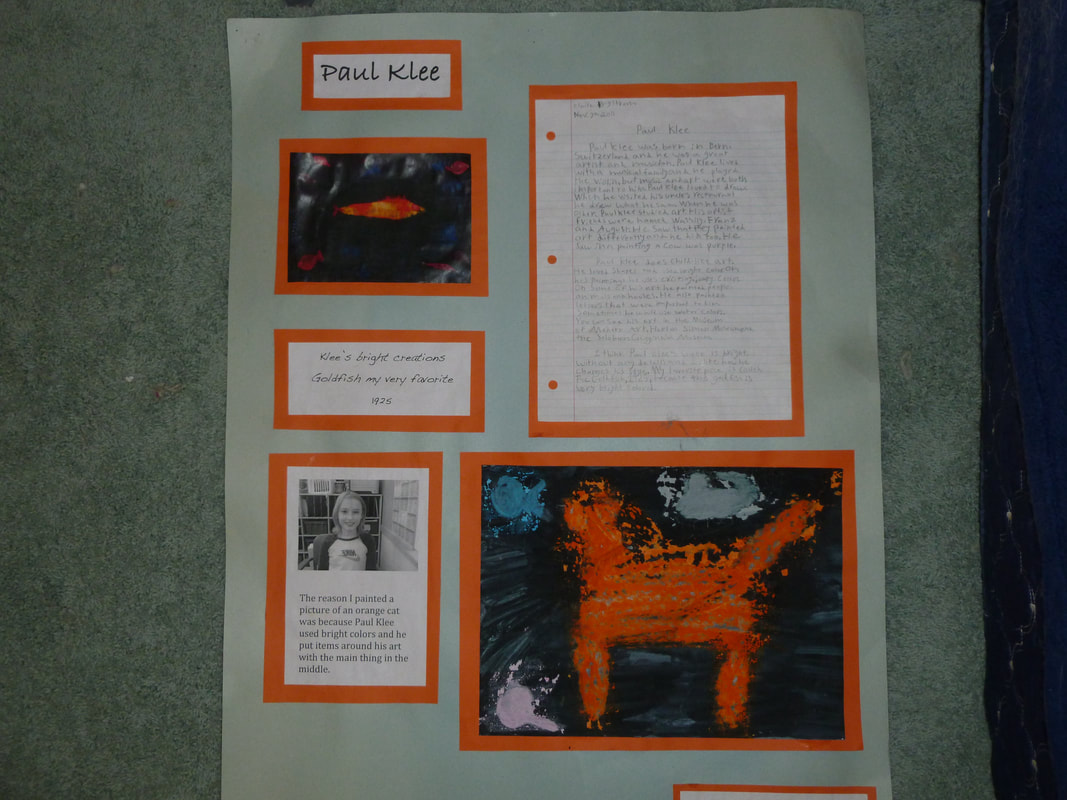

Observations by Becky Engstrom 3-5th Grade TED Specialist, Gastineau and Harborview Schools BACKGROUND As a specialist serving intermediate students grades 3 through 5, I have always rotated language arts units on a 3-year basis to be sure students are offered an eclectic mix of content supported by lessons to improve reading and writing skills. One of my favorite units has always been an art biography unit. Students would do research on an artist collecting pertinent facts by taking notes. They would use the notes to write a three paragraph report on their chosen artist. They would write haiku poetry about their artist and the art work. They would create a piece of work combining their artist’s style and beliefs with their own, then they would support the piece they created with a description explaining their reasoning behind their work of art. All these parts are then mounted on a poster board which has always made for a beautiful display. CHANGE After signing up and committing myself to the study of Artful Teaching, the first thing I wanted to do was change this unit to create more opportunities for authentic artful thinking using a variety of thinking routines from different thinking dispositions. I experimented with a selected artist to experience different routines that would help students when they finally selected the artist they wanted to study. I chose Frederic Remington to learn and model different thinking routines. We did a verbal See/Think/Wonder in table groups with different Remington pieces, then used the same pieces to do a verbal Beginning/Middle/End. We experienced Step Inside with a work from Remington. We studied desert vocabulary (mesa, plateau, canyon, butte, saguaro, ocotillo, etc.) and used that vocabulary to create tableaus. ON THEIR OWN After students selected their artist, gathered notes, and wrote their report, I selected a piece from their artist, printed it out, and students wrote their See/Think/Wonders on the printout. Students also selected a piece from their artist that they wanted to attempt to turn into a Tableau (step inside). The student who selected their piece would become the tableau director and had to put people in position until they were satisfied with the outcome. It gave me a good understanding of which students had excellent communication skills and which students needed improvement. It also helped me see the students who noticed many details and the ones who did not. I would have to bring focus to areas in the piece with questions… “What direction are they looking?” “What is their hand doing?” The amount of information I received from this one activity was a true eye-opener! Students also extended their thinking by creating a piece of art that connected their own thinking to the artist they were studying. CRITIQUING AN ARTIST Students wrote a research paper on the artist they picked. The last paragraph was their opinion of the artist they selected. I especially enjoyed reading these paragraphs. NEW PROJECTS DISPLAYED IN RETROSPECT

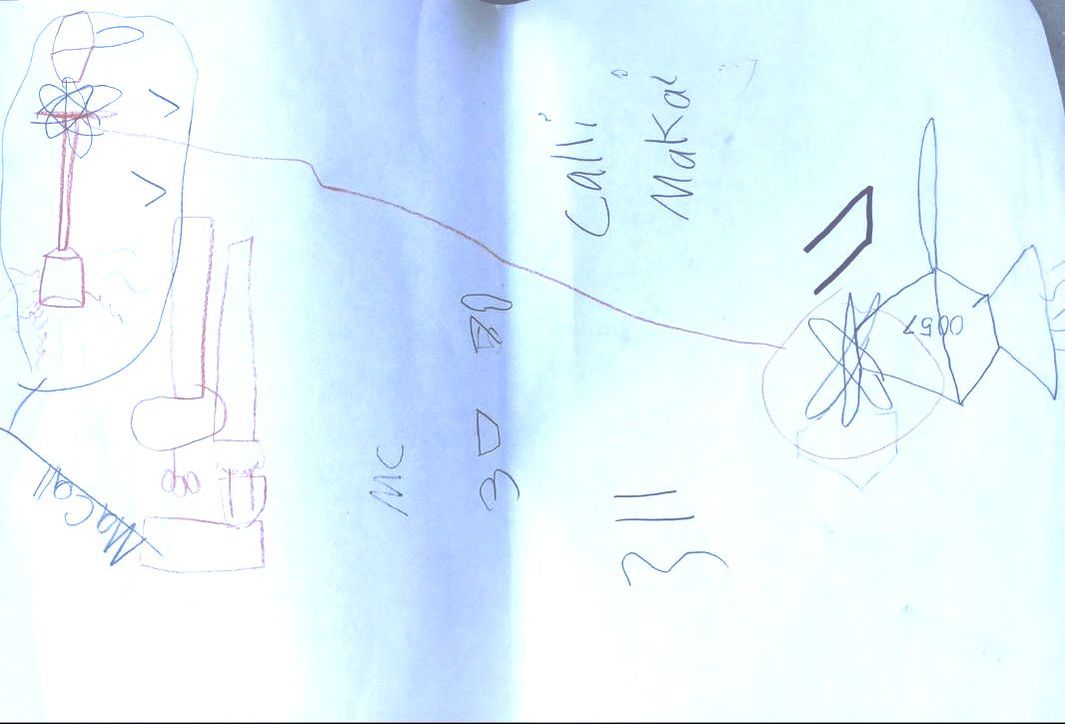

Although I believe the old poster board displays were more visually pleasing and beautiful, the new displays showed more artful thinking; the most beautiful moment to catch is proof of a brain in action. Whereas the old displays had more writing skills involved, the new supported the process by which learning took place. It was inspiring to watch the students make incredible observations. To listen to the details noticed to create the tableaus was a treat. To read their observations of the students’ chosen artist was deeply satisfying. Teaching became more passive, as if I handed the wheel to the students because they were ready to drive. It’s scary, and wonderful at the same time. By Allison Smith 1st Grade, Auke Bay School Artful Teaching has transformed the way I teach. One example is when we studied weather this year. In the past, when we studied about wind, students made wind flags measure the wind on a scale of 0-2. The flags are made from fabric and cardboard cut for them ahead of time. The emphasis in this lesson had been on the measurement of wind, not so much on the creation of the wind flag. This year I decided to use Artful Teaching to introduce the concept of wind and measuring wind by showing my first grade students different paintings showing wind and wind gauges. That got me thinking...if students are looking at pictures of different wind gauges, why not have them design and create their own wind gauges and test them? What started with me looking for images to introduce a lesson turned into a great STEM project for my students. First I asked students to See, Think, and Wonder looking at 4 paintings showing wind at the same time. Then I asked them to think about what was the same about all of the paintings. “It’s windy!” Was the common answer. Students then talked in small groups about how they knew it was windy. “The curtains are blowing.” "The horses’ manes and tails are blowing.” “The person is flying a kite.” Are a few of the things they shared. Our next step was to work in small groups to look at pictures of different tools designed to measure the wind. I explained to students that we would be looking at these wind gauges and asked them to discuss how they thought they worked. The conversation was lively with lots of pointing at parts of the pictures to explain how they worked. After students had a chance to look at and discuss how the wind gauges worked, I gave them the challenge of creating their own wind gauge by making a plan, building their wind gauge, testing their wind gauge using a fan, and revamping their wind gauge as necessary. It was an amazing process to watch and be a part of. Students were engaged in all parts of the project, taking time to create their designs as well as testing, revamping, and testing their gauges again. After our wind gauges had been tested and redesigned, students took them outside to measure the wind speed on a scale of 0-2. The student created wind gauges worked just as well as the flags we used to make! At the end of the project, I asked students to share what they learned. Here’s what stuck with me:

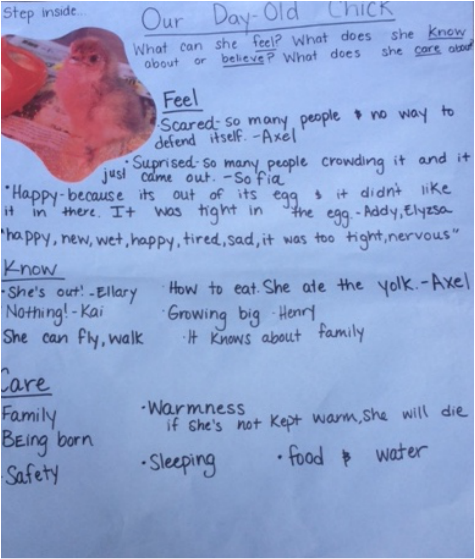

“If your wind gauge doesn’t work at first, change it and try again.” In the end, this lesson was just as much about the design and creation process as it was weather. Thank you Artful Teaching for expanding my horizons! By John Wade 7th Grade ELA, Floyd Dryden Middle School By Maura Selenak Kindergarten Teacher, Harborview School It’s January and I’m sitting at the carpet with a group of kindergartners. “Why do you think the character in the story said that? What was she thinking?” Hands shoot into the air- “I’ve built a snowman before!” “My mom read this book to me before.” “Can I go to the bathroom?” They are eager to share their experiences and what they know to be true. However, urging a group of five and six year olds to perspective take-- whether we’re reading a book, or I’m asking a child to think about his friend’s point of view when they’re having a disagreement-- can be hard. Perspective taking is the ability to take the perspectives of others and apply it to your interactions with them. It is something that we work on over the course of the entire year in kindergarten. When my Art Lab group chose to experiment with the Step Inside Artful Thinking Routine, I was intimidated. Choose a person, object or element in a piece of artwork, and step inside that point of view. Consider: what can the person/object perceive or feel? What might the person/thing know about or believe? What might the person/thing care about? I worried that this thinking routine would be too abstract for my kindergartners, or that they wouldn’t be interested. Boy was I wrong. This routine was so successful on the first try that I came back to it again and again for the remainder of the year. Each time I was blown away by the students’ insights, responses, and eagerness to share. What did this thinking routine look like in the classroom? Snapshot 1: Our Day-Old Chick For this thinking routine, we used an image of a chick that had just hatched in our classroom. Some of the students’ thinking was recorded on a poster during the thinking routine: Snapshot 2: Friendship

This thinking routine happened toward the end of a read aloud of Timothy Goes to School by Rosemary Wells. In the story, Timothy is excited to go to school but when he gets there, Claude tells him he is wearing the wrong thing day after day. We paused at an image of Timothy and I asked students to “Step Inside” and pretend that they were Timothy. Some of the students’ thinking was recorded on a poster during the thinking routine. by Michaela Moore JDHS, ELA & Drama To introduce the play, Death of a Salesman by Arthur Miller, I first put an image from a poster of the play on the overhead and had the students go through the Thinking Routine of SEE/THINK/WONDER:

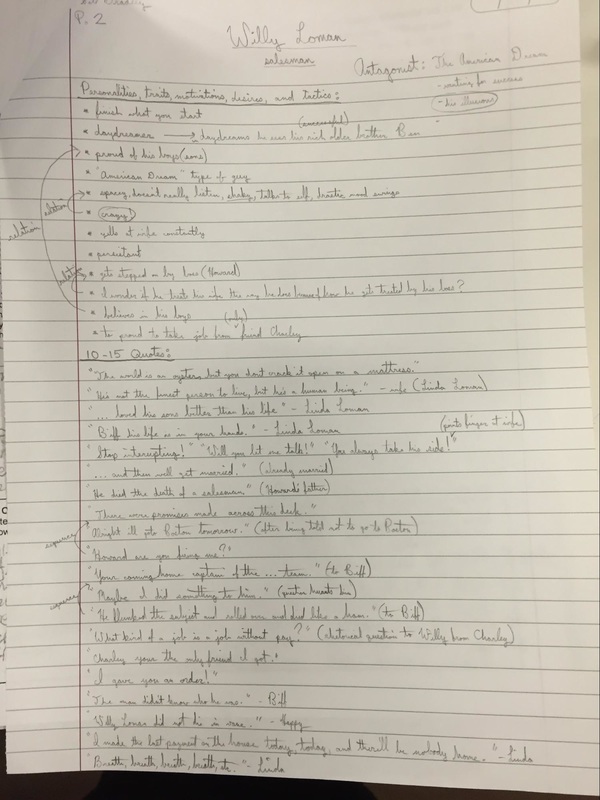

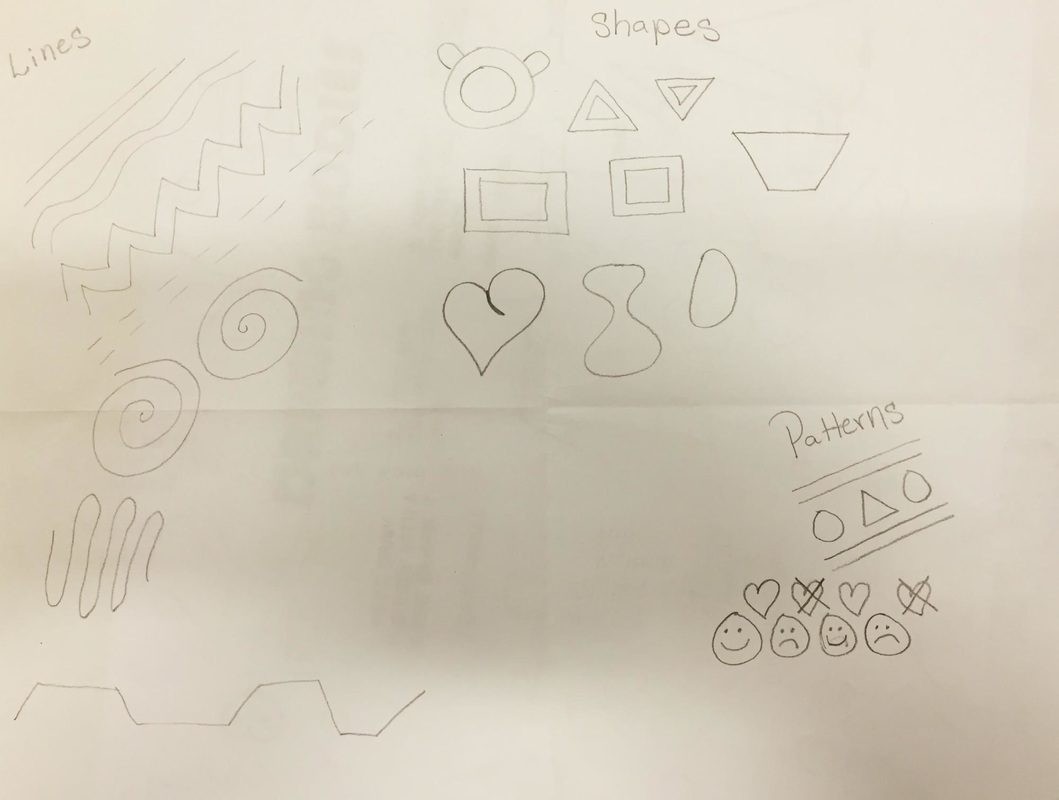

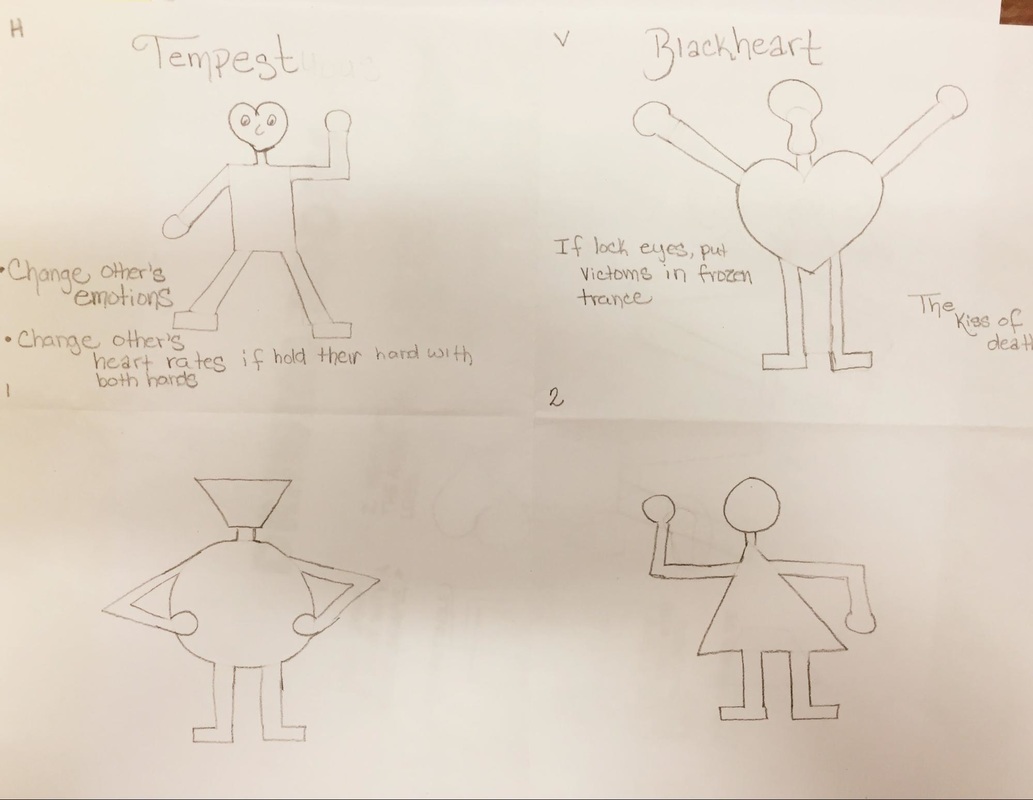

After this Thinking Routine, I asked the students to complete a Crowdsourcing activity about Arthur Miller. The students found information quickly about Arthur Miller and came up and wrote in a word splash on the whiteboard fun and important facts. We took a few moments to discuss surprises and interesting facts found in table groups and in whole group. Then I asked the students to prepare for notes: I introduced the 4 main characters from Death of a Salesman to students and asked them to choose one character that they would focus on in their project and notes. I instructed the students to write anything important down about the character (personality, weaknesses, strengths, choices, goals, motivations, etc) while we watched the play. After we finished watching and discussing the play, I passed out the text of the play and asked the students to fill in holes in their notes about their characters AND to add important quotes said by their characters, or important quotes others said about their characters. Once, these notes were complete, I taught the students step by step how to draw a caricature of their character beginning with a sketch first and then moving into their final draft. We first discussed the idea of caricatures and how they were different from real portraits or pictures. We discussed the symbolic nature of caricatures. (Learned from work of Richard Jenkins).

2. Show the students how to draw a caricature from lines, shapes, and patterns and have them draw your example, and have them rough draft sketch out a caricature of their Death of a Salesman chosen character. 3. Show the students how to turn their sketch into a real caricature of their chosen character. 4. I showed the students how to do Richard Jenkins’ inking technique (using sharpie to outline your pencil drawing) and then coloring technique (how to use colored pencils to get different shades and different textures) and shared with the students Richard Jenkins’ helpful handouts on hair and faces.

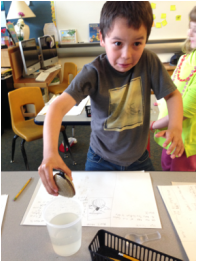

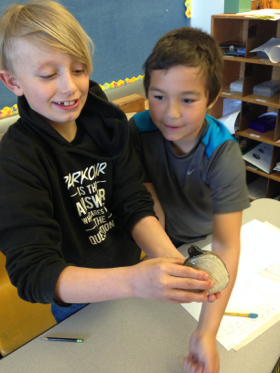

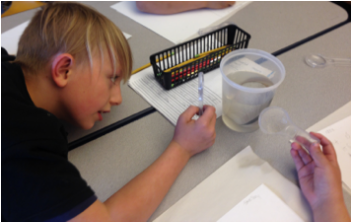

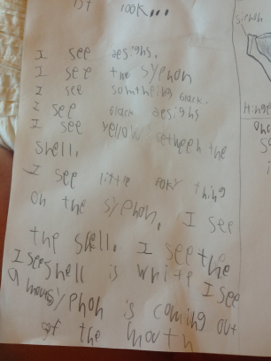

by Carly Lehnhart Glacier Valley Elementary, 2nd grade Artful Thinking has become such a natural part of my teaching. I have found that it sneaks its way into everything. I continue to be amazed at the engagement and effort that my students put in during and after a Thinking Routine. It brings the focus back to the process and emphasizes curiosity and critical thinking skills, which are two things that I strive to facilitate. One way in which Artful Thinking has made a huge impact for me and my students is in science. I have always used science notebooks as a way of recording our observations and findings, but this year, they have been a lot more successful. I am realizing that Artful Thinking is what I have to thank for that. My students are structuring their observations and notes in ways that are mirroring and combining a lot of the routines that we have tried. Without leading them in a formal routine, I find that they are using the language that has been modeled when they make notes in their science notebooks. Woohoo! I have been loving using Artful Thinking as an introduction to a unit to spark interest and identify our background knowledge, as well as at the end of units as assessments. This specific lesson was kind of in the middle. My students had just been to DIPAC to learn about mollusks. They had been introduced to what a clam was, gotten to see one, and had an overview of the parts. A couple of days later, a parent showed up in the morning with a bucket full of clams and asked if I wanted to use them. I obviously threw out the old plans and quickly came up with an idea of how to use them in my classroom. Artful Thinking immediately came to mind. I started out with a See/ Think /Wonder with this picture. This is a routine that we do A LOT.

I started the lesson doing a Looking 10 x 2 Thinking Routine. They immediately forgot about the picture, because a live clam on your table is way more interesting.

1st look: Quick and simple. They had about 3 minutes to write down words, phrases, or sentences about the clam in front of them. Some second graders struggled with this, so it turned out to be more like 5x2 for some. Here is an example of one students 1st look:

|

ArtStoriesA collection of JSD teachers' arts integration classroom experiences Categories

All

|

|

|

Artful Teaching is a collaborative project of the Juneau School District, University of Alaska Southeast, and the Juneau Arts and Humanities Council.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed