|

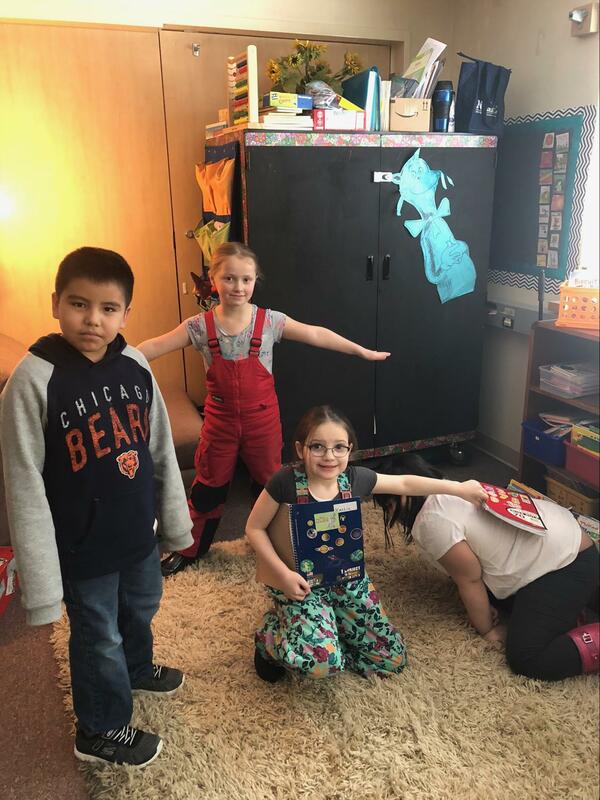

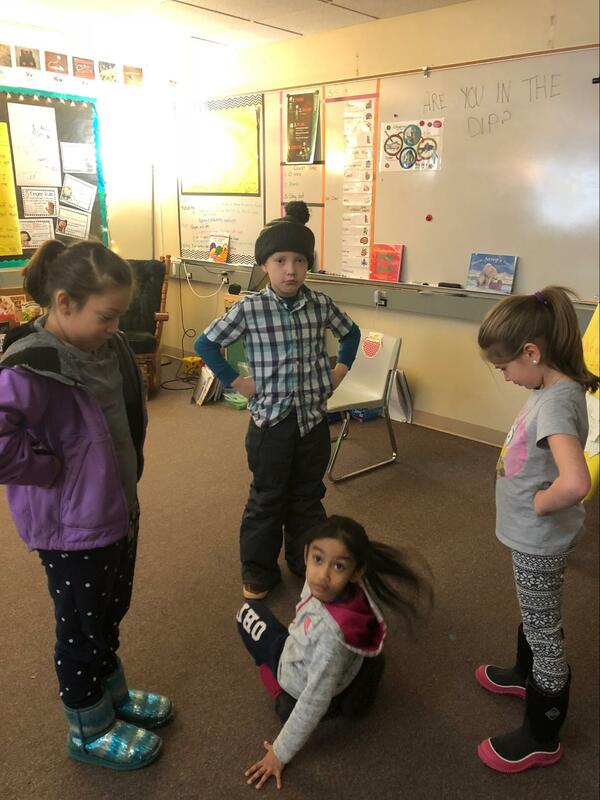

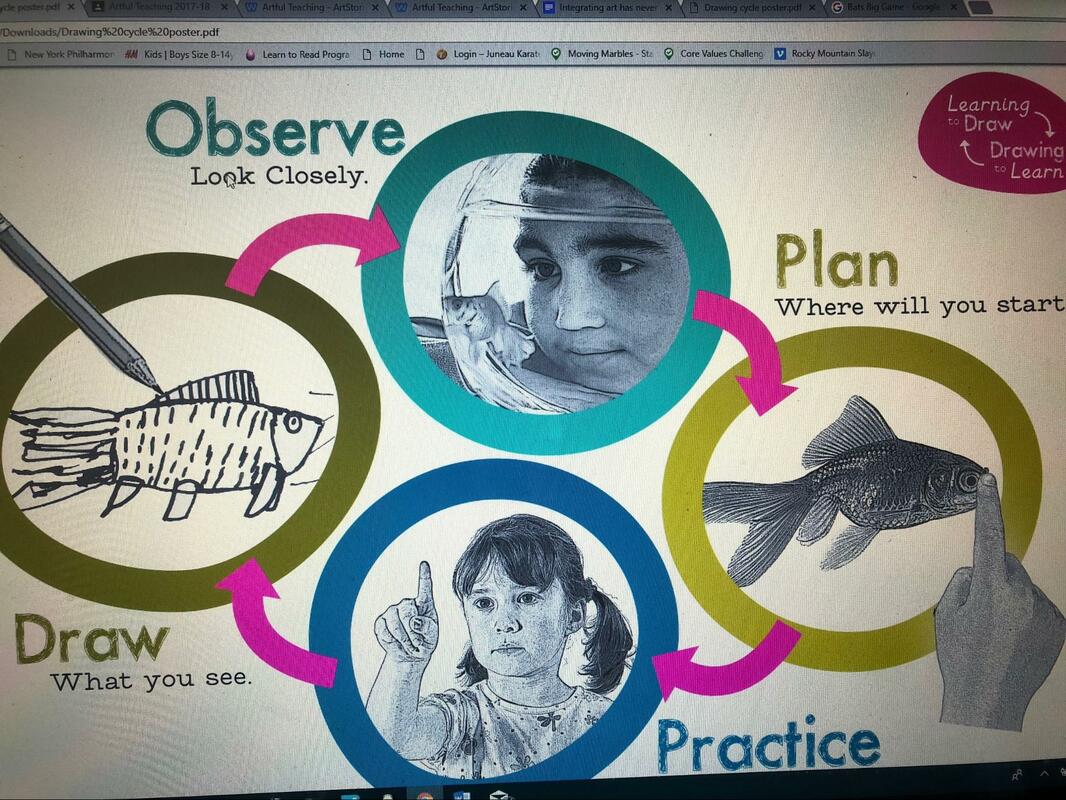

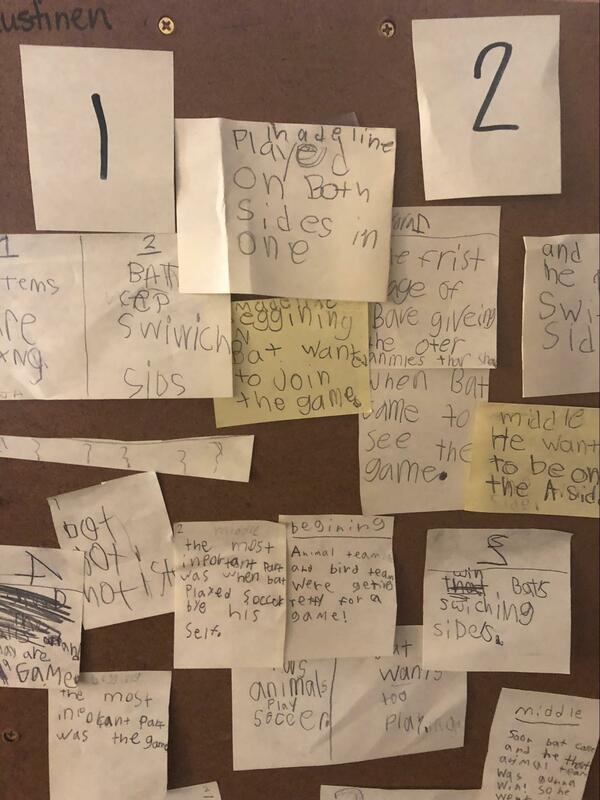

by Shawna Puustinen Primary multiage, Riverbend School Artful Teaching has giving me so much to think about. I have spent the last decade integrating art into my language arts, science and social studies units. An art project here, a drawing there, a model of a neighborhood made out of milk cartons. That’s art, right? I guess it never occurred to me that I could use art to teach social studies, math, science and language arts. I would love to say that this realization resulted in a complete overhaul of my teaching, in which every lesson was embedded with artful learning. Of course, I can’t say that. I can say that I have embedded artful learning routines into my day (well, not everyday). I am slowly but surely building my understanding and gaining the skills needed to be an artful teacher. Our school has adopted the One School, One Book initiative. For the past two years our amazing PTO has picked one book and purchased a copy for every student, staff and employee in our building. The idea being that we will all read the book and be able to talk about it. Teachers read the book in their classrooms, students take their copies home and the school hosts some school community events and activities. This year, Arctic Aesop’s Fables by Susi Fowler was the book chosen. Each classroom picked one of the fables from the book to design a bulletin board. What started out as a small cooperative art project ballooned into a full-fledged unit of study. We looked at characters, settings, problems, solutions, and the moral of each story. We then compared the two stories, looking for similarities and differences. We had lots of great discussion about friendship and good sportsmanship. On what I thought was going to be the last day before I was to leave on vacation, the students worked together in small groups to create tableaus for their favorite parts from one of the two stories.

On Monday I boarded a plane for a wonderful week in the Florida sun, completely forgetting that months before I had promised the kids that we would do a puppet show. Guess who didn’t forget. My daughter, who just happens to be one of my second graders this year. Ugh! Aren’t there rules about having your own kids in your class? Just kidding. It has been a blast having my daughter in my class. So, that’s how it happened. I got back from vacation and my daughter reminded me and the rest of our class that I had promised a puppet show. Clay, sticks and imagination… I am going to start this section by confessing that I hate puppetry. Nothing makes me feel sillier than interacting with a puppet. I have tried...really. I have spent countless uncomfortable minutes having conversations with Impulsive Puppy and Slow Down Snail. It always leaves me feeling...weird. So, I knew that trying to teach a puppetry unit was going to stretch me in many ways. I started the unit with dot sticker popsicle stick puppets. The kids each got to draw eyes and mouth on their dot sticker and put it on a tongue depressor. Most of the kids were pretty excited, but a few were less than excited to be holding a tongue depressor puppet (oh, how I could relate to them). With great enthusiasm, I demonstrated arm positioning, puppet posture, large puppet movements (walking, running, going up and down stairs, lying down, getting up, etc), wrist movements (yes/no, looking up/down/around, reading, etc.), puppet emotions, and voice projection. The same few less-than-excited puppeteers actively tried to sabotage our puppetry lessons. Their poor tongue dispenser puppets experienced great head trauma while being repeatedly banged against tables and the floor. They refused to participate in voicing activities and their “I am too cool for this” attitudes were starting to spread. I was ready to call it.

As soon as the popsicle sticks were attached the kids were becoming their puppets. A few kids, were working together creating quick puppet skits. I still had one very reluctant artist. He was about as excited about creating his puppet as he had been about using a puppet. The kids got to pick one puppet to leave at school for the puppet show, and then take the other puppet home. One girl came back the next week with more than 10 little clay creatures she had made at home. It was neat to see how her creatures evolved from simple to very detailed and sophisticated.

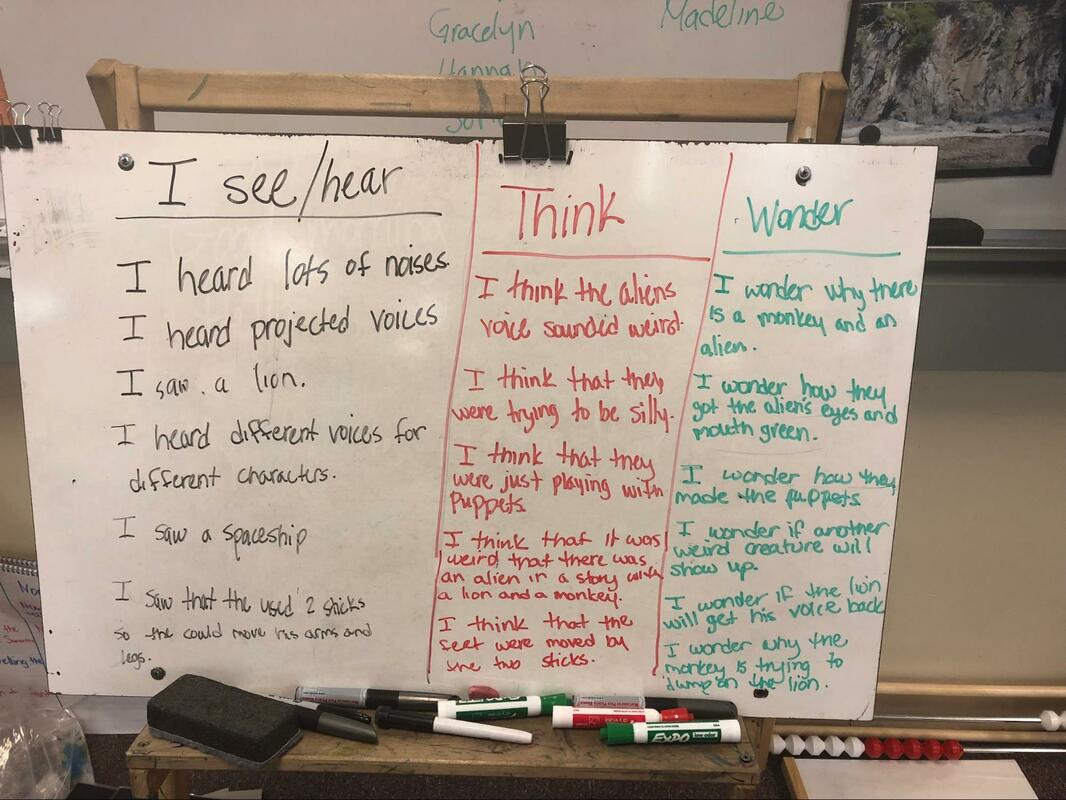

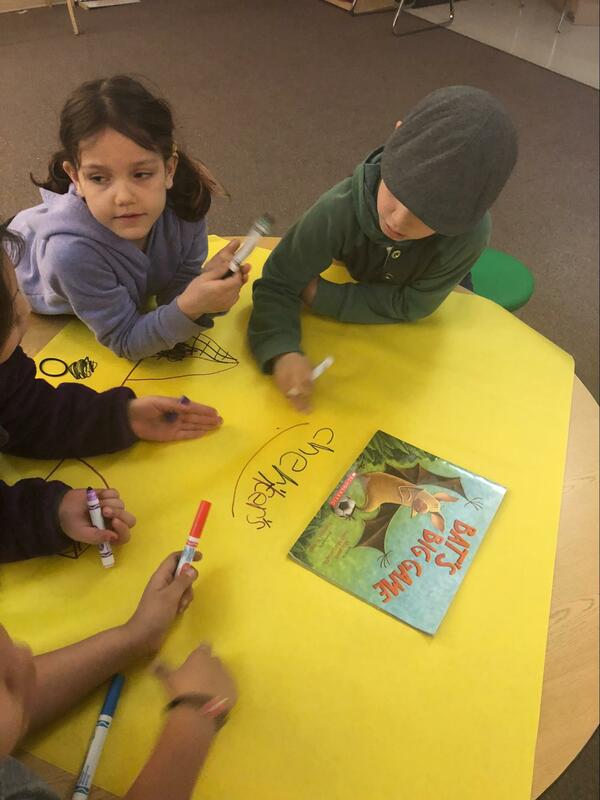

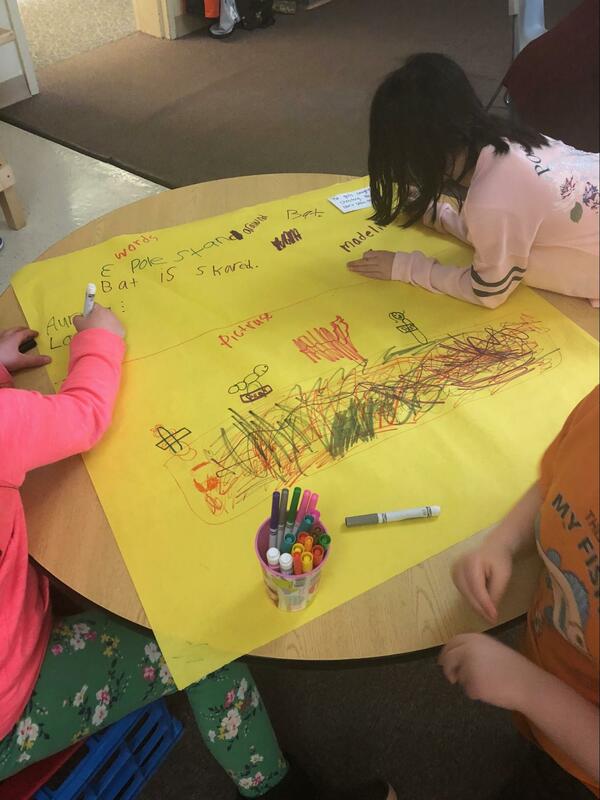

During a morning meeting time, we watched two videos of people putting on shadow puppet plays. After watching the videos, I used the “See, Think, Wonder” thinking routine to help my kids process what they had seen. I was very impressed with what they observed. Many picked up on the techniques the actors were using to make their characters come to life. They noticed things like how voices changed from one character to the next. How the puppeteers used multiple sticks to move different parts of the puppets. They noticed the props changed from one scene to the next. They wondered about what would happen next in the stories and how the puppeteers made their puppets. As I watched and listened to them share with each other, I saw engagement, inclusion, success. The playing field was level. Each one of them, regardless to their background, learning needs, age, grade, etc., was able to share something that they saw or thought or wondered. Since the tableau process is very familiar to my students, I used the same process to get them started with planning their puppet skits. The groups did their thinking and sharing just like in tableau. When they were ready to plan, I had them go to tables to brainstorm what they would need to make their scenes works:

Tomorrow is our big production. The kids haven’t even finished the scripts, but I think it will be okay. I told them that I would video each of their skits and then we could all watch them together on the big screen in the room. All but one seemed really excited about this. As I am sitting here writing this, I can’t help but smile. These kids have done some amazing work in the past few weeks. It goes way beyond close reads, reading comprehension and craft projects. They connected to a story, stripped it to its bare bones, extracted the underlying message and then rewrote it in their own words. They worked cooperatively in groups. They explored new and old art forms. They created. They problem solved. They observed. They asked questions and found answers. They supported one another. They tried new things. They took risks. They stepped outside of their comfort zones. They failed. They persevered. It would be hard not to be proud of the work they have done. So tomorrow, no matter what happens, I will stand and applaud each of them with genuine admiration.

And it all started with one fable, from one book.

0 Comments

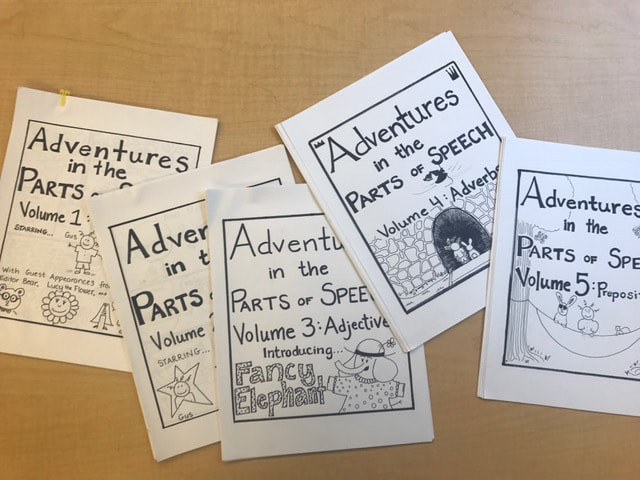

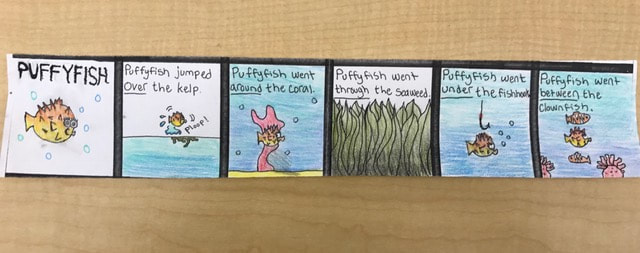

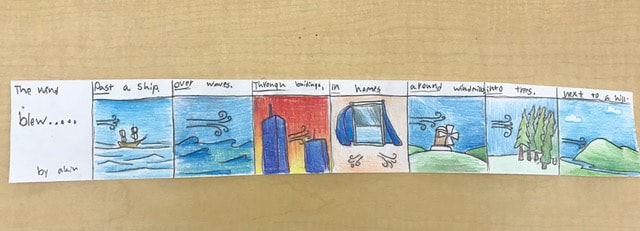

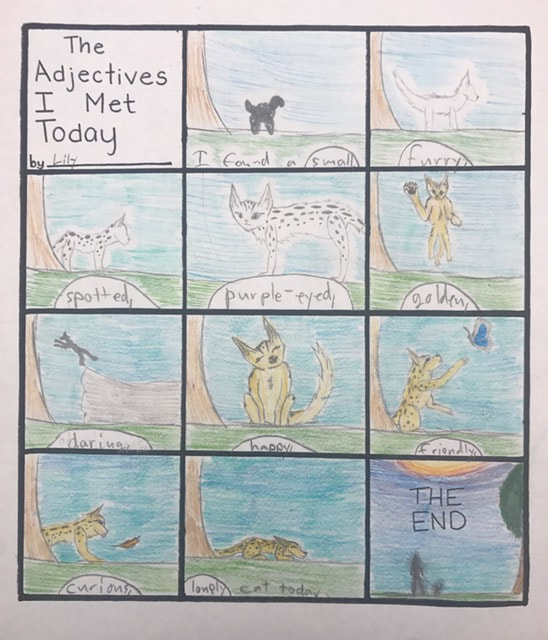

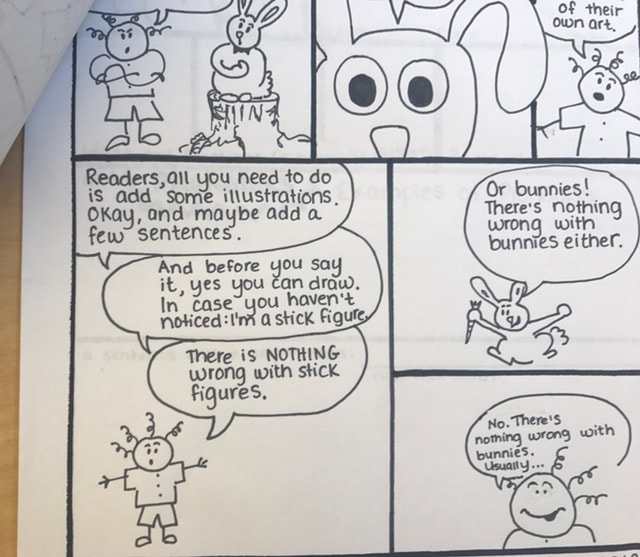

By Samantha Davis 8th Grade Language Arts, Floyd Dryden Middle School As I began my year in Artful Teaching, I was so excited to learn new ways of integrating arts into my eighth grade language arts classroom. During a fall unit about the parts of speech, I set a goal of working art into grammar instruction, both through the products students create to show their learning and through my own teaching methods. Though I eventually added in some of the strategies I was learning about in the Artful Teaching workshops, including tableau, I primarily focused on integrating comics into the parts of speech unit. Our learning objective was for every student to show their understanding of the parts of speech through a series of mini-comics. Because I wanted to begin our learning with a form that integrated art into instruction, I created short comic books introducing students to each of the eight parts of speech. As students moved through the unit, they learned to expect that each new concept would both begin and end with a comic: they’d learn about the part of speech through a comic, and they’d eventually produce a comic showing their understanding of the part of speech. We’d start by reading a comic about the part of speech aloud in class. Voices were strongly encouraged, and the actors in class often rose to the occasion, much to their classmates’ amusement. These comics not only introduced the content-area concept, it also forced me to take the same risk I'd be asking students to take: creating and sharing original artwork. This helped create a safe environment for creating and making mistakes. After we read the introductory comic, we’d discuss the part of speech, practice identifying it in different sentences, analyze why it matters in writing, and respond to writing prompts focused on that particular part of speech. Finally, students would show their knowledge of the part of speech through their own comics. The prompts for these comics were designed to encourage creativity, provide structure, and focus on the objective. For example, one comic was called, “The Adjectives I Met Today.” For this comic, students would pick a noun and invent a variety of adjectives for that noun to “meet.” Students used the artwork to (literally) draw connections between nouns and adjectives, thus representing the abstract concept of nouns modifying adjectives in a concrete, visual way. For the students’ preposition comic strips, the prompt involved picking a noun or pronoun and an action verb. Then, every successive frame had to be a prepositional phrase. Again, students were using art to demonstrate their understanding of an abstract concept. While the prompt and the prepared templates gave even more reluctant students the confidence that they could be successful, students were encouraged to extend and adapt the prompt as well. In every class, some students would take the initial prompt in new directions, without losing their ability to demonstrate their understanding of the content goals. In these situations, students would approach me with a proposal for another approach—“What if I…”—and we’d discuss how that approach would still work to show understanding of the content goals, or we’d modify it so it would still show the understanding while honoring the student’s unique approach. Some students were reluctant about their drawing skills. But stick figures were okay: after all, the star of “Adventures in the Parts of Speech” is a stick figure. In some ways, this approach to these projects helped establish a classroom culture where the expectation is not to avoid mistakes, but to try even when we’re unsure. Finally, one of my favorite moments of this unit--and in every unit in which students produced a piece of visual art--is the moment when the student work is displayed in the back of the classroom (our classroom gallery). Without fail, the day after their work is posted, students gather to observe the creations—always searching for their own, but also seeing how others responded to the same prompt in completely different ways. Often, they’re also assessing learning and asking new questions about the concepts. In the days and weeks after I post their work, I will often find students, on their own or with their classmates, browsing the gallery. So in this final stage, students are learning from each other.

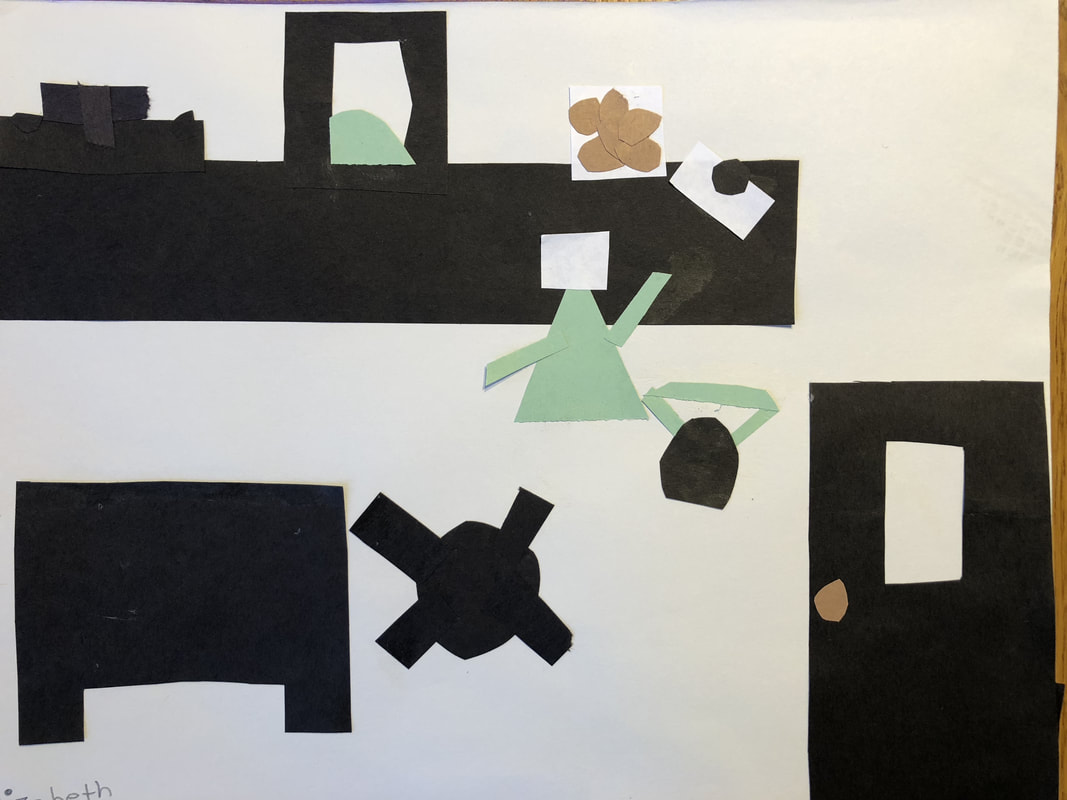

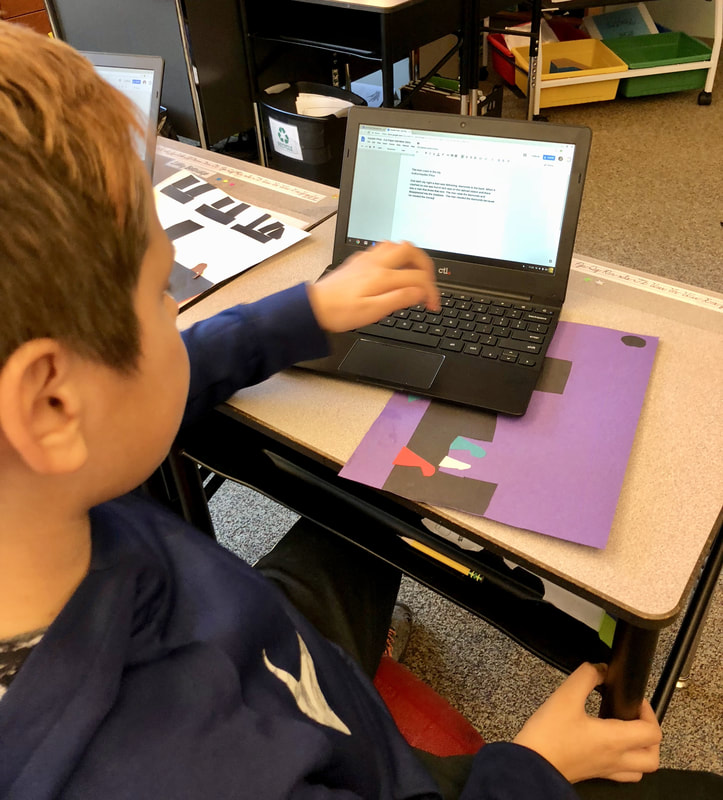

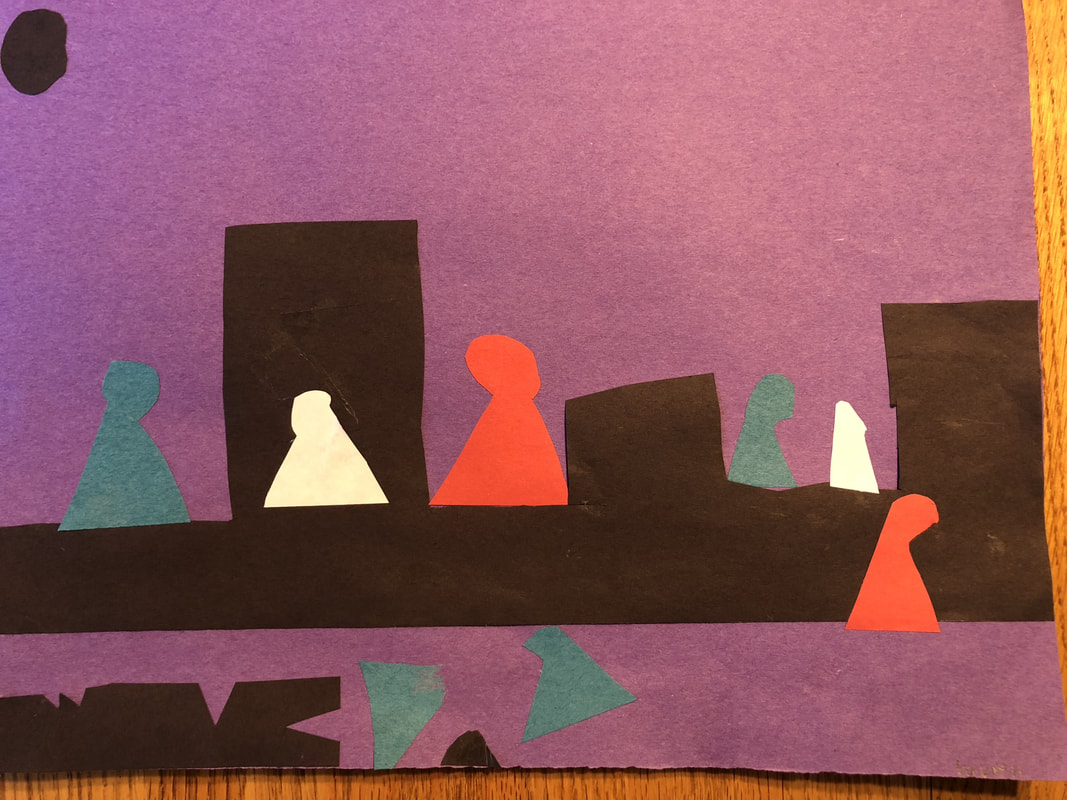

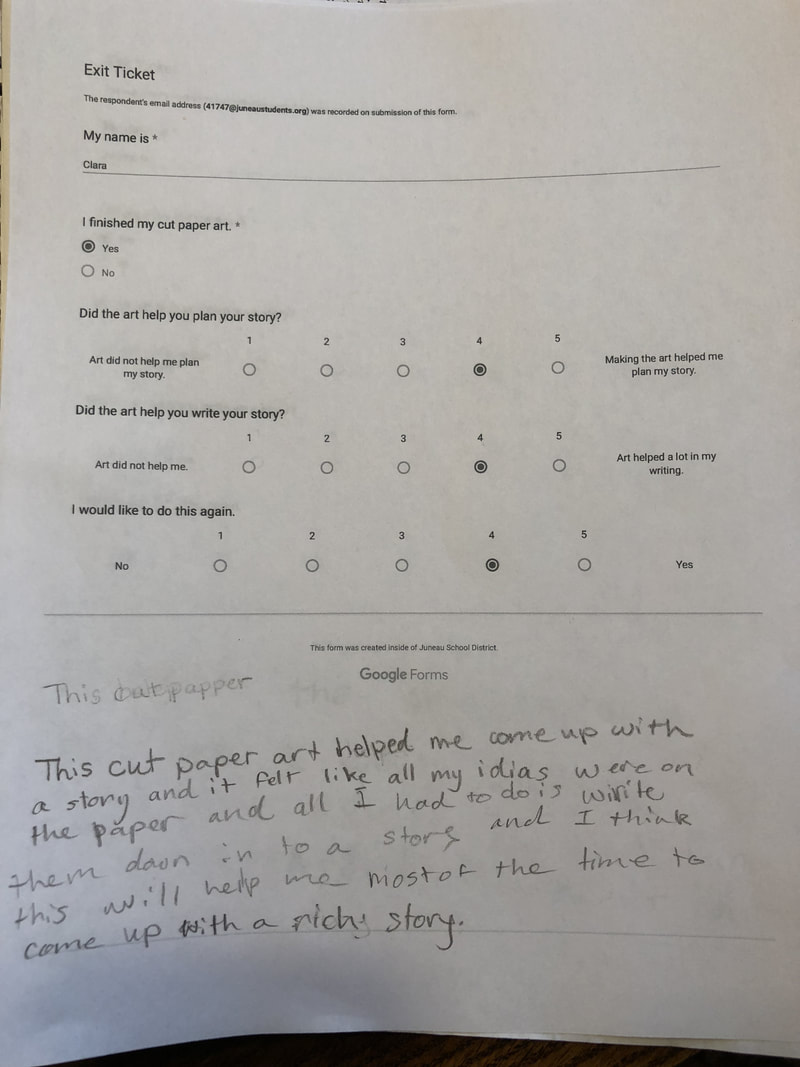

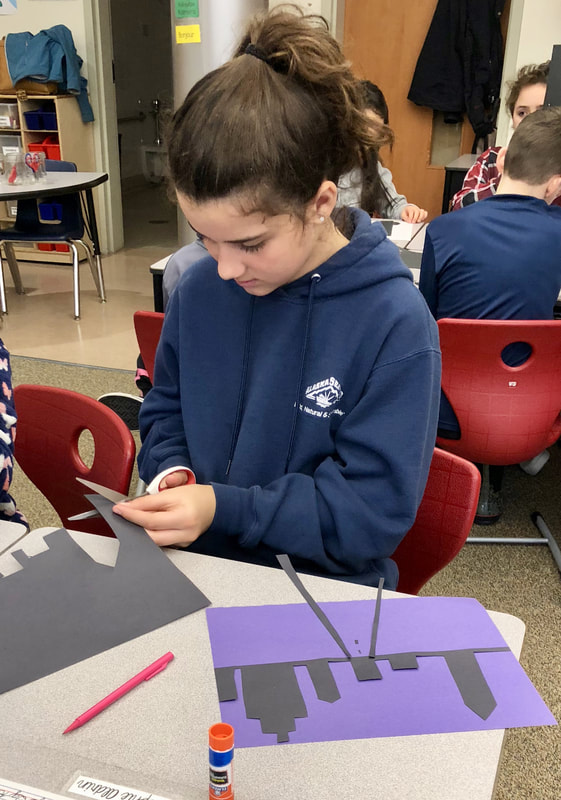

So, why was it important for students to construct and demonstrate their understanding through the arts? First of all, I found students far more ready to engage with a pretty dry concept—the parts of speech isn’t exactly the stuff of fireworks—when it was introduced in the fun, humorous, and accessible medium of comics. Furthermore, when students began creating their own comics, it allowed for on-the-spot formative assessment along with natural extensions. It was easy to see which students had a mastery of the concept and which still needed more one-on-one instruction. Plus, with students so engaged in the project, it often gave me to provide that extra instruction as soon as I identified the need for it. Even more importantly, I’ve found that the use of art to show understanding builds community in the classroom. It forges connections: students who feel more confident in their artwork can encourage and support those who feel more apprehensive about their drawing skills, while students who felt more confident about their understanding of the content concept (in this situation, the parts of speech) can question and guide those who might still be confused. Comics--whether students are reading them or creating them--invite humor and conversation. In the classroom, as students worked on their comics, there was a constant buzz of conversation as they checked their understanding and ideas with each other. While everyone created their own comic, they worked together to create, sharing and exchanging supplies—“Can I use that crayon?” “No, I’m not done with it quite yet” “Oh, here, I have one you can use”—in ways that felt natural and needed no prompting from the teacher. Similarly, students began to use the artful thinking disposition of see-think-wonder before it’d been formally introduced, as they shared their work with each other, making observations and asking questions. The work was both individual and collaborative. When I think about this question, “Why was it important for students to construct and demonstrate their understanding through the arts?”, I think about these scenes: students gathering in front of the gallery to see, think, and wonder about each other’s work; students sharing art supplies and ideas; students laughing and celebrating each individual’s unique approach to a project. In short, when students construct their learning through the arts, it encourages both individual creativity and a supportive classroom community. Though I’m in my twentieth year of teaching, my participation in Artful Teaching has consistently provided me with new challenges, ideas, and inspiration over the course of the year; I’m already looking forward to building on all I’ve learned this year with next year’s students. by Nadine Marx 4th Grade, Auke Bay Elementary Too often I see a blank stare on my students’ faces when they are tasked with writing. The pressure of an assignment empties their brains of ideas and they don’t know how to start. After participating in Jamin Carter’s workshop, Cut Paper: A Pathway to Creative Writing, I was excited to try his way of warming up students by integrating art into the writing process. Students would learn about art elements (shape, size, color, space) and create a piece of art using construction paper, scissors, and glue, and in doing so, would plan the setting, characters, and problem in a story before being asked to write a well-developed narrative. Before teaching Jamin’s lesson, I led students through mini-lessons on story structure, problem and solution, figurative language, and how to write and punctuate dialogue. Then, over two days, I taught Jamin’s lessons as scripted in the materials provided at the workshop. Students enjoyed learning the gestures that went along with the art elements. They loved playing Pass the Setting, and were excited that they would create their own picture of a problem that they would write about. On Day 3, I was surprised (and delighted) that most students had no problem thinking of a problem to illustrate, and were able to get right to creating a picture. One student needed some time to think of a problem, but then easily finished his picture within the time given. Students were asked to create a paper scene of the problem, or the middle of their story, showing setting, time of day, characters, and lastly, give a hint as to how the problem might be solved. On Day 4, students got started with their narrative writing. I was clear about my expectations, showing them a scoring guide I would use to evaluate their writing (thinkSRSD.com). Because of increasing expectations for 4th graders to type responses on assessments, I provided a google doc for students’ writing. Three of 23 students opted to write their story in their journals, while the others typed. When students had their first draft of their story done, I asked them to complete an “Exit Ticket” on Google Forms about the project. I asked if they finished their art, if the art helped them plan their story, if the art helped them write their story, and if they would like to do this again. Questions 2-4 were answerable on a scale of 1 to 5, 1 being on the No end, and 5 meaning Yes. Offering these choices may have been a mistake, since students gave a lot of 3s, making data less telling. After reviewing answers, I printed the individual forms, allowing space at the bottom for a written explanation of their answer. This was more helpful. But because I was asking students for multiple edits and rewrites, most written comments were harping on the amount of work this project was. Apparently they did not like to edit. A few written comments expressed the students’ enjoyment of the project. My own observational data led me to believe that creating the picture of the problem before writing the story was highly effective. Students had created the setting, characters, and problem and had thought about the solution before starting to write. I thought that students seemed to be writing their stories more quickly, and just as I had felt that the story flowed out of my pen after having done most of the thinking and planning beforehand during the workshop, I thought that students’ writing seemed to be an easier process for them. I did not see students staring blankly at the screen or page, and if they were, it was because they were trying to think about how to satisfy the expectations of the scoring guide. Would I do this again? Absolutely! It did take a good bit of class time to teach the art concepts and go through practice to get them ready for their part. My class worked on this during the last week of March, and had we done this earlier in the school year, we could have had more opportunities to create additional cut paper stories and write them. At this late date, we had to finish assessments and complete the last of our 4th grade tasks. Next year, I would teach this in August or September, and use the strategy several times throughout the year, making the time invested in the background knowledge more useful. Trapped! By creating art, and thinking about art elements of shape, size, space, and color, students planned the setting, characters, problem and solution for their narrative stories while engaged in creating with paper, scissors, and glue. They planned setting while choosing a background color to represent day or night, or interior lighting. They cut out trees or furniture or buildings and further developed their setting. They thought about character development while shaping their characters, choosing colors and shapes that would represent who their characters where and how they would interact. They added shapes to represent the problem of a broken vase, a cookie jar that was out of reach, a train that crashed or stolen jewels. Then they developed a visual clue of how their problem could be solved. While working on their art, students talked with their table groups about the process, and got more ideas, and explained to each other what each part meant. When it was time to write, their stories were written in their minds, and they only needed to get them out in words. Often teachers ask students to write and then give them time to create visual art as a reward for getting their work done. This now seems backward to me. Having intentionally created art with a meaningful setting, characters, and plot, students were more than ready to write.

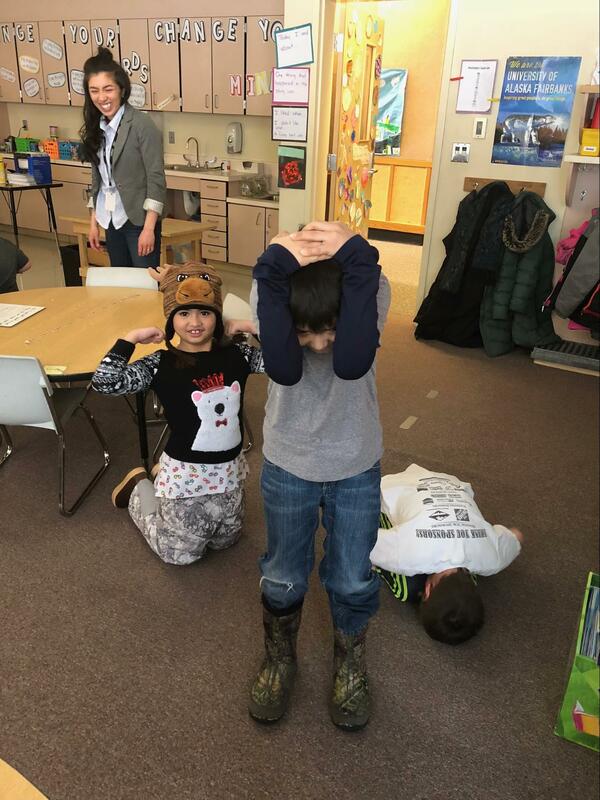

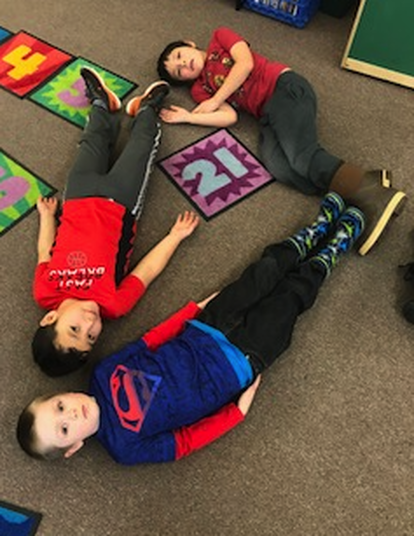

by Katy Goodell 1st Grade, Riverbend Elementary ,Artful Teaching has become part of every day in the classroom. Whether it’s the vocabulary I’m using, a thinking routine, the actors toolbox, or tableaus, some part of each of our day involves techniques and skills I have acquired this year through this amazing opportunity. I have decided to share some pictures of some things I have done in my classroom using tableaus. I personally believe that handing students a paper and pencil doesn’t actually show all that they can do, especially when it comes to assessments. So, this year I chose to use tableaus as formal and informal assessment tools. In these first three photos you see students laying on the floor in different shapes. We went through the actors toolbox then dove into some tableau work with plane shapes. During this time, students were learning all about different kinds of shapes in math. I used this time to include some tableau work to assess how the students were understanding sides, vertices, and angles. You will notice that all three tableaus are on the ground. One of the characteristics of a tableau is that there are levels. Students seemed to really struggle through figuring out how a plane shape could have different leveles. They were so stuck on the fact that it’s two dimensional and the fact that they see these shapes as something flat. Next year, when I go through these lessons again, I really want to discuss in depth that just because a plane shape is flat doesn’t mean it has to be flat on top of a surface. It was really interesting to see the students struggle through this. When we debriefed after our tableau work, students were surprised and seemingly caught off guard when I brought this to their attention. This made me reflect a bit on my teaching during these lessons. It showed me that I didn’t explain that just because it’s a plane shape, it doesn’t mean that it has to be “flat on the ground.” With all of that being said, the kids were still successful during this process and they weren’t using a pencil and a piece of paper. They were reflecting on the different attributes of plane shapes and discussing how they could create those shapes as a team. Each team was able to create a plane shape without support from anyone other than their own team. It was fun to watch them go through Think, Share, Plan, and Create. They could make it through Think and Share, but once we got that far, they were so excited to plan and then create that most of them would just start it. I had a hard time with that at first. I couldn’t decide if it really was appropriate to stop them when they were so excited to learn and create together. But I quickly got over that because it caused more issues than success. Throughout the year I have gotten more and more comfortable with the tableau process, which has me extremely excited for D.C. and next years implementation! In the next set of photos, you see students at different levels. You also see students being assessed once again. It was so great to have a tool to use this year aside from a paper and pencil. This second set of photos was taken during my formal observation earlier this year when my principal came in to observe. I had been talking about Artful Teaching and how much I had been enjoying spending some of my time outside of school at these amazing workshops when my principal said, why don’t you show me what you have been doing… There are so many times where I feel that we as teachers feel like we have to show what we are doing with the curriculum and our implementation of it, that we forget there is an art form to teaching. Artful Teaching has helped me express my teaching art form in ways that I don’t think I would have come up with on my own. During this lesson, my students were being assessed on what they had learned through the week about solid shapes. They had to consider the faces, verticse, sides, and angles. This was a very challenging lesson and assessment tool. We had done quite a bit of work with our foam solid shapes, and I knew my students had learned and understood quite a bit about the attributes about solid shapes, but they honestly blew me away during this assessment. Each group went through Think, Share, Plan, and Create. Through out this process, I was walking around listening to the different thoughts and plans they had. Their consideration for all of the attributes of these shapes were amazing. This really gave then the opportunity to think about the shapes that each solid shape have within them. As I walked around the room I heard groups discussing how the cube has square sides and how a pyramid has a square base. These are things that we had discussed but when they actually had to apply those attributes to a real life creation of these shapes, they had to think more deeply about what each shape really looks like. Some groups were more successful than others. I found that students had a hard time deciding if the attributes that one friend had shared were actually true in regards to the solid shape they had chosen to create. It was also hard for students to decide what each person was going to do. They were all so excited about what they had learned that they wanted to play every part.

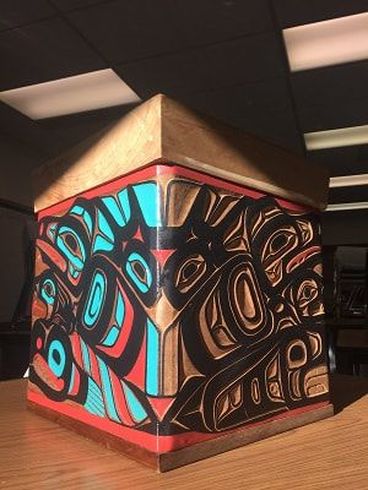

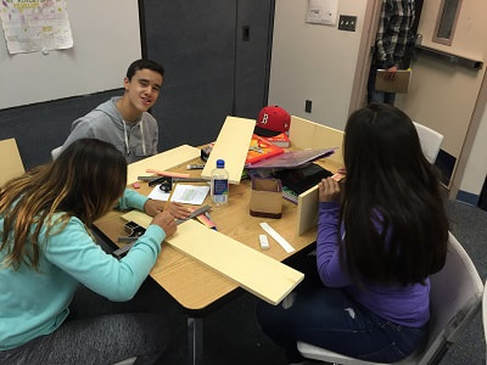

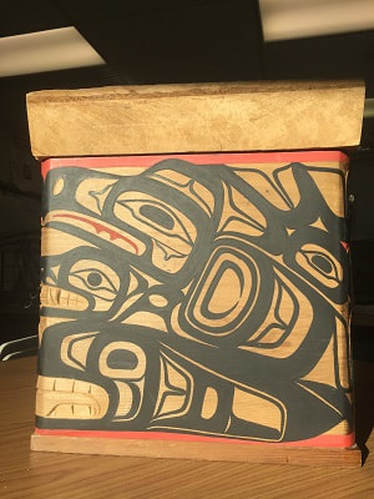

We did these tableaus a few different times so each group had an opportunity to create different shapes. As we continued the work, the tableaus got more and more detailed. I am so grateful for the opportunity to be part of such an amazing experience. I have grown so much as an educator and I can’t wait to continue this experience next year with my peers and my students. by Tennie Bentz Dzantik'i Heeni Middle School, 7/8th grade Bentwood Box created by Leroy Hughes Eighteen primarily Alaska Native students enter the classroom full of energy on this fall afternoon. Most of them struggle in math and it is the last class of the day, so no one is ready to buckle down to learn about measurement, surface area, volume, symmetry, or ratios and proportions. Then Ruby Hughes, our Cultural Specialist, brings in the most beautiful Bentwood Box any of us have ever seen. It is large, approximately 24 inches on each side. Intricate formline designs are carved on two sides and painted on the other two. The students settle down a bit and I start to hear sounds of excitement as they begin to look at and touch the box. They are hooked. Not only are they in the presence of a masterpiece, they are about to create their own. Students settle into their seats with the Bentwood box at the center of the room. We begin the I See, I Think, I Wonder thinking routine and discuss what students see when they look at the box. What makes this box so beautiful? Is it the size, the shapes, the colors, the symmetry? Groups look closely at the box and explain how they think the box was built. Some of our students have built one before so they can help explain the process to others. Many students wonder how they will ever be able to complete something so complicated. Step by step, we tell them. It’s going to be a long process, but in the end they will have a tangible item that they will be able to give as a gift or keep as a memory of the challenge to come. A couple of days later, Ruby brings each student their own rectangular piece of yellow cedar from Hoonah. Sealaska Heritage Foundation helped cover the cost of the cedar which is fairly expensive. Ruby explains the importance of precise measurement and we show students examples of boxes that were square and others that are not. Students see the beauty in symmetry. Perfectly bent corners, straight lines, tops proportional to the bottoms. Armed with a ruler, pencil and their new knowledge of measurement, students begin measuring precisely to ¼ and ⅛ and even 1/16 of an inch. Some of the students fly along, making their measurements while others fall behind. One girl starts to wander about the classroom bothering others. At first she won’t tell me why she is wandering and then I realize, she doesn’t know how to read her ruler. She’s never been asked to measure something so precisely, especially when mis-measuring by something as small as ⅛ of an inch will end up creating a box that is no longer symmetrical and square. This young lady would rather give up than end up with a less than perfect product. I convince her to sit back down and together we began to measure. We create a template because remembering which line is which on the ruler is too difficult for her on this day. Soon she has her measurements complete, her corner angles drawn correctly and the rest of the class finishes soon after. The project flies by. Day after day as students saw, sand, and chisel their way towards a final project. Ruby works patiently guiding half of the students through the process of building their boxes. I work with the other half of the class tying in the math behind the art. We learn about surface area by creating wrapping paper and volume by filling the example boxes with cubes. Fractional measurements are converted to decimals and percents. Standard systems of measurement are converted to metric. On and on the math goes with students always excited to stop with the math so they can just go work on the art. Soon the boxes take shape. Ray Watkins visits Dzantik’i Heeni and he and Ruby take a few kids at a time downstairs to steam and bend the boxes into their square shape.The other students wait impatiently with me. They want to see if all of their precise measurements and persistence sawing and chiseling have paid off. Will their final product have the lines of symmetry and the perfect bends in the corners? Soon students begin to carry the boxes back upstairs, smiles on their faces. Most of the boxes are nearly perfect, a few aren’t quite square but Ruby is sure that she and Ray can magically fix them overnight. The next day, when the students return, everyone has a perfect box. Soon the students began new measurements to create perfectly fitting bottoms and proportional tops. The boxes were nearing completion for many students. The experience of building their own Bentwood box was enough. Others however wanted to take the box further and create their own formline design to put on the outside. We spent some time looking at the Colors, Shapes and Lines on the masterpiece Bentwood Box that had served as our inspiration through this entire process. The colors were few but bold. Red, black, teal and natural wood. Ruby taught us the names and relationships between the shapes. Ovoids serve as the center from which U-shapes extend. We learned that the shapes rarely stand on their own, but connect and flow from one form to another. To me this was the perfect analogy for how math should be taught. Fractions should not stand on their own, there needs to be flow, a relationship and connection between the math and real life application. This was the perfect opportunity to teach ratios, proportions, similar and congruent figures and lines of symmetry through art. Ruby taught the students how to make ovoids using lines of symmetry and I created an activity where they had to measure the height and width of the ovoids and then create new ovoids that were similar using ratios and proportions. Most of the students ended up with a set of ovoids that they could use as a template when creating the formline design on their boxes. Some students quickly realized that they could avoid the math and just draw ovoids within ovoids to create their template. Whichever method students chose to use, the concept behind math supporting art was cemented. Students are still working on their formline designs. One young lady is trying to get in touch with her grandparents to learn more about her lineage so she can put the correct clan crests on her box. She is an inspiration to me and reinforces the need for more projects like this one. She doesn’t do much in math class and did very little of the work when we worked with the math behind the art. Some may call this a failure of the project when looking at it from a math perspective but this student is so proud of the masterpiece that she created that she is taking the time to make sure the connection to her family’s history is accurate. She plans to give her box to her grandmother in Angoon. That in itself proves the project was successful in my eyes. Acknowledgments:

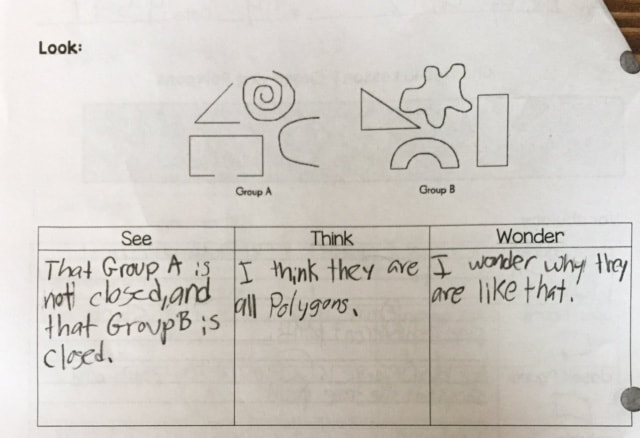

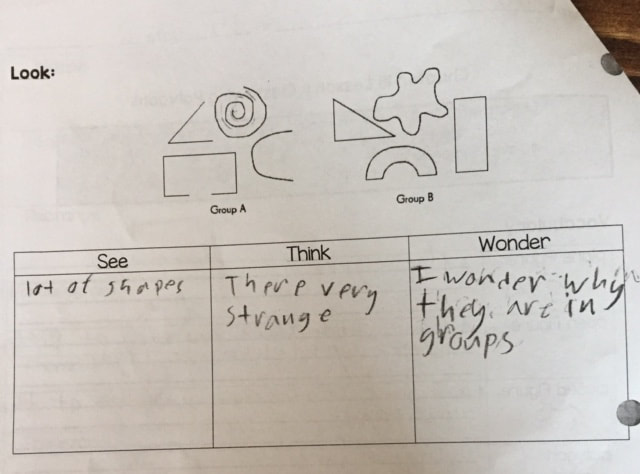

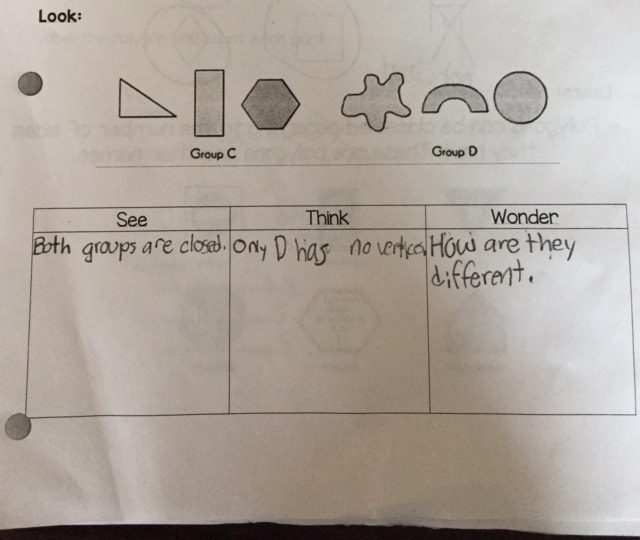

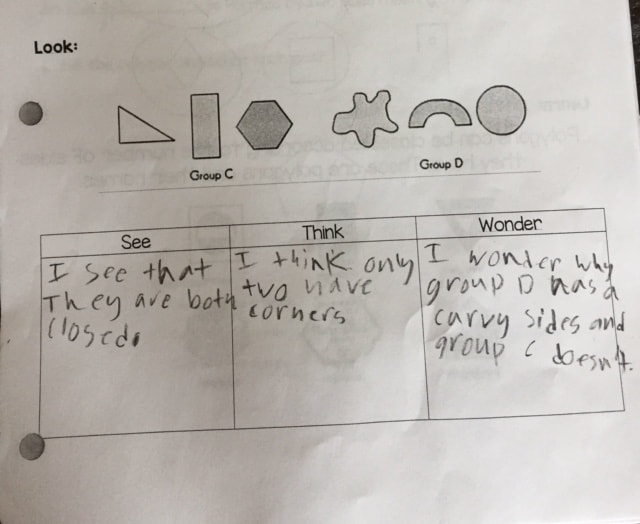

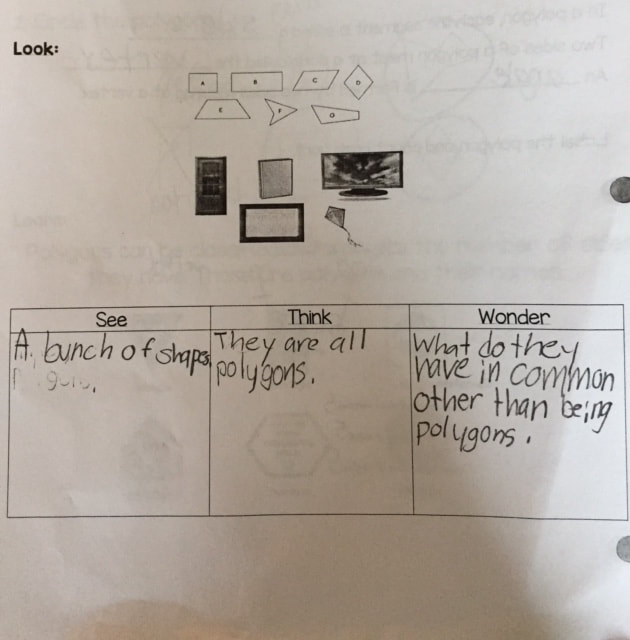

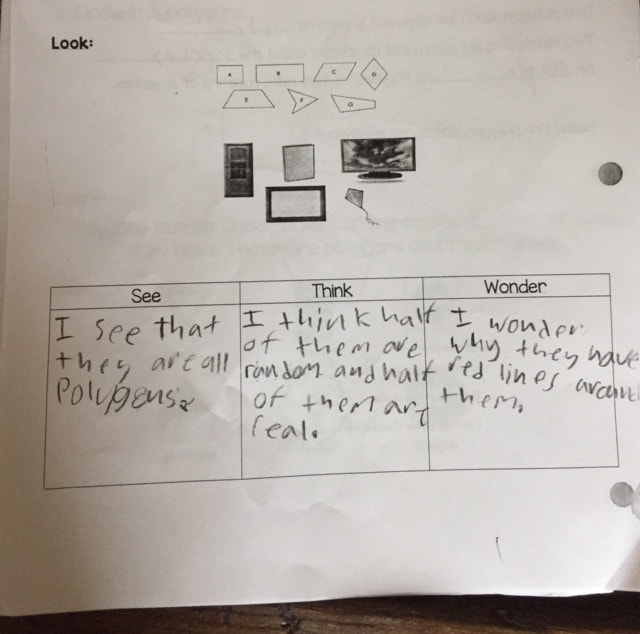

I owe a huge thank you to Ruby Hughes. Her calm presence and patience was an inspiration through this process. Without Ruby’s help and support, this project would have been a disaster. Ray Watkins’ help behind the scenes made this project streamlined and successful as well. Thank you to Sealaska Heritage Institute for your generous support providing the yellow cedar and to the Artful Teaching grant for purchasing colored pencils for the final box designs. By Marnita Coenraad 3rd Grade, Riverbend Elementary School As I began my Artful Teaching journey last year, I was excited to find how seamlessly I was able to integrate Artful Thinking routines into my literacy instruction. I found that Reading Portraits added depth of knowledge to our reading of biographies, and art seem to provide an entry point for struggling readers. This year that trend continued with our study of tableau. As I became more familiar with the routines, I branched out and used them in science and social studies as well. But even as I experimented with these new content areas, I found that bringing the routines into my math instruction was more challenging. I made it a goal for the spring semester to bring Artful Teaching to my math lessons. For each new math lesson, I create a guided notes sheet. These notes serve as guide through the lesson, as well as a reference that can use when completing their independent practice or homework. I decided that I would include a thinking routine at the beginning of each math lesson. I hoped that this would stimulate thoughtful discussions and promote student discovery of mathematical concepts. The following is an introduction to geometry lesson. I used the thinking routine “See, Think, Wonder” to help students discover characteristics of open/closed shapes, polygons, and special quadrilaterals. 1. Students started by looking at groups of open and closed shapes. I did not give them any indication as to why shapes were grouped in this way. Students then completed at least one entry for See, Think, and Wonder. I did not ask students to write in complete sentences for this exercise. You can see that students entered the lesson with varying degrees of prior knowledge. 2. After some direct instruction in open versus closed figures, students repeated the thinking routine with two more groups of figures. I was happy to see that immediately began experimenting with the new vocabulary introduced during the lesson. Again, some students were already familiar with geometry vocabulary, while others were engaging with it for the first time. 3. After direct instruction in naming polygons and their parts. We repeated “See, Think, Wonder” for a final time. Students again used the new vocabulary in their observations and inferences. Several students noticed that some of the shapes were line drawings, or “random” shapes, and some were “real,” meaning photographs. This breaking into two groups was an unexpected result of my having two groups in the previous two routines. I had hoped that students would notice they all had four sides. Although there were a few misconceptions along the way. I was happy that students were able to construct their own definitions for open shape, closed shape, and polygon. With help, we also discovered the characteristics of special quadrilaterals like rectangles, parallelograms, and trapezoids. I have taught similar geometry lessons that are vocabulary rich, and it can be difficult to get students to engage with the new words and their meanings. Teaching this lesson through the Artful Thinking routine encouraged students to construct their own definitions and provided a safe space to try out their new vocabulary terms. Since this lesson, we have used the art of Kandinsky and Mondrian to identify and name 2-dimensional figures. Students are highly motivated to find and share the shapes they see.

I am continuing to experiment with using art in my math instruction. I recently used Navajo blankets to review symmetry and introduce area. While arts integration in math does not come as naturally to me as in other subjects, I am enjoying the challenge. More importantly, I see students participating in class who are usually reticent to volunteer in math discussions. Since we teach art terms throughout elementary, I have found that students are comfortable analyzing and discussing art. The consistency of thinking routines coupled with the familiarity of art has made math more accessible and enjoyable for many of my students. by James White 6th Grade Math, Dzantik'i Heeni Middle School

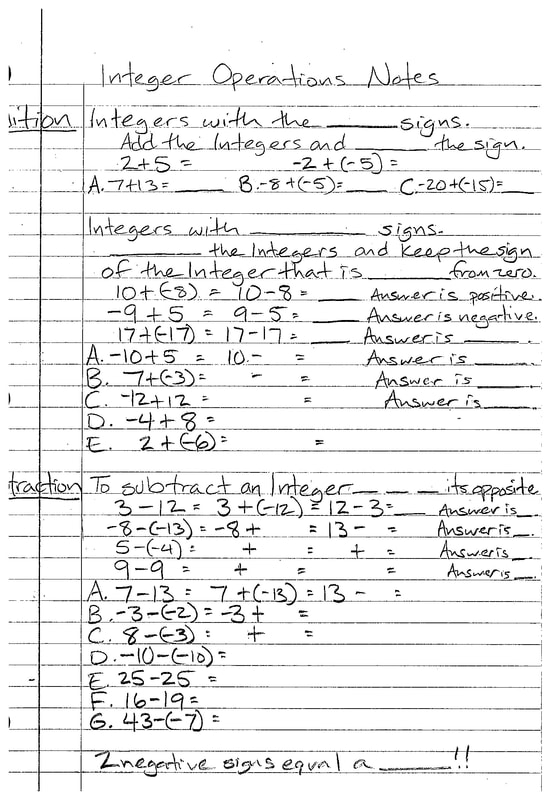

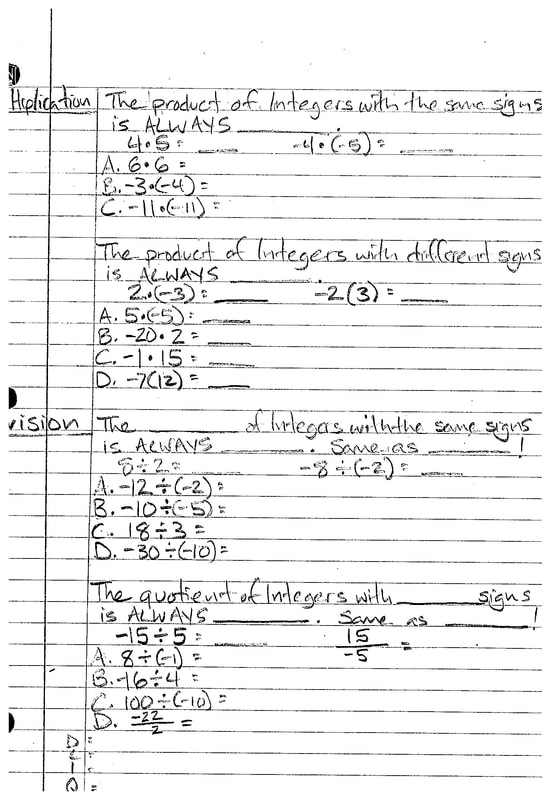

I chose to teach my 6th grade math students about Integers (positive and negative whole numbers) and Integer Operations (+,-,X,/) through Curriculum Based Readers Theatre (CBRT). Students learned about CBRT, properties of Integers and the rules for performing operations with Integers. I followed a basic sequence of direct instruction note taking on the concepts (similar to the routines already established) and then used sample CBRT scripts to introduce CBRT. Students then developed, rehearsed, and performed a CBRT script that they wrote as a class. I assessed the effectiveness of using CBRT to teach the rules of Integer Operations by having these students take a pre and post test and then analyzed the results. Integers and Integer Operations are critical concepts for advancement through pre-algebra, and the first concept these students will learn at the start of 7th grade. 7th grade mathematics teachers stated that they wanted to have 6th graders exposed to these concepts by the end of their school year so it was more familiar by the time they taught it at the start of the following year in their classes. Being that it was the end of the school year, I also decided to incorporate CBRT as a fun way to engage my students in learning about a performance art with the support of drama specialist Roblin Davis, a local actor and fellow Artful Teaching participant. WEEK 1 - Intro to Integers & CBRT I started Week 1 with an introductory lesson on Integers by having my students learn common vocabulary (integer, positive, negative, opposite, etc.) and concepts by leading a note taking lesson where students filled in blanks to these definitions and important ideas. "The next day Roblin Davis joined our class and we introduced CBRT by discussing gestures and sound effects and then reading an Introduction to CBRT script. Here is a video of students learning the technique of emphasis when speaking: The next lesson involved my class taking what they learned about Integers and adding to their knowledge by reading a CBRT script about Integers. We also discussed where and how to incorporate gestures and sound effects to make our reading more informative and entertaining. Students had fun adding the gestures to this script and making sound effects! We finished our Introductory lessons to CBRT and Integers by doing math worksheets which practice writing integers and comparing/ordering them. I was able to incorporate a lot of the gestures and sound effects from the Integers script while kids worked through the practice problems. WEEK 2 &3 - Integer Operations and CBRT Script Writing I started the next week doing a pre-test of students knowledge with Integer Operations (+,-,X,/) within 10 minutes and also had them complete notes which introduced the rules for these operations. Roblin joined us for next class day as he helped guide us through the script writing process based on the rules for integer operations we learned the day before. Here are some great resources to help get your students thinking about the writing process and guide them through writing a script: It took both of my classes some time to get the important concepts out and then outline the setting characters, gestures, etc. needed for writing the script. This took us two class periods to develop our scripts but at the same time students were repeatedly rehearsing the rules for operations with integers so I felt as though it was time well spent. Here are the final versions of our scripts! During the next class period we rehearsed our scripts and recorded them. I showed the students their recorded rehearsals and introduced them to the CBRT Assessment Rubric below: While watching their rehearsals, students were asked to complete a self assessment to better understand how they were graded and identify areas they could work to improve on during rehearsals and final performance. The final sequence of lessons was adapted as timing did not allow for a performance before the post assessment, but that would be the suggested method. At the end of the week, students were given an Integer Operations Post-test to complete in 10 minutes. It was the same exact questions as the pre-test along with the following comprehension/reflection questions. The results from the post test showed students definitely learned from the CBRT unit on Integer Operations. Students in my Period 1 class Integer Operations Camp, averaged 8.3% increase in the tests. 13/15 students increased their overall scores. It was not that surprising that the students whom didn't take a specific part in the script (not as engaged during the writing, rehearsals and performances) had much lower increases than those that did (including the two who scored lower on the post test). Students in my Period 2 class Integer Operation Olympics averaged almost 15% increase in the tests. 18/20 students increased their overall scores. This class had some huge gains in percentages like 45% increases and many whom are on IEPs or have lower grades on previously taught concepts achieved higher than their norm. I also asked students to answer the following comprehension questions about CBRT and our Integer Operations unit.

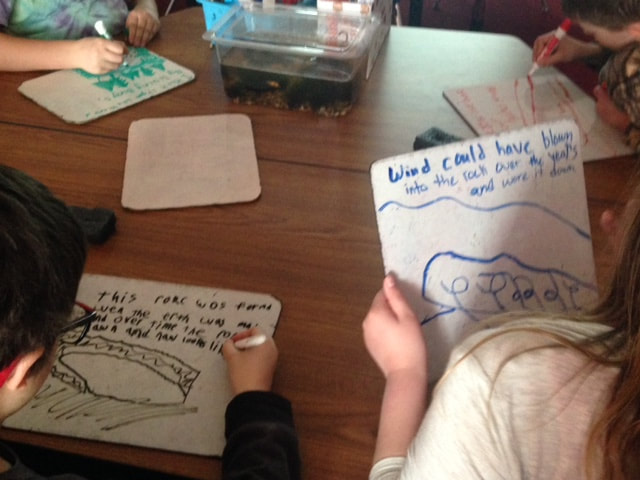

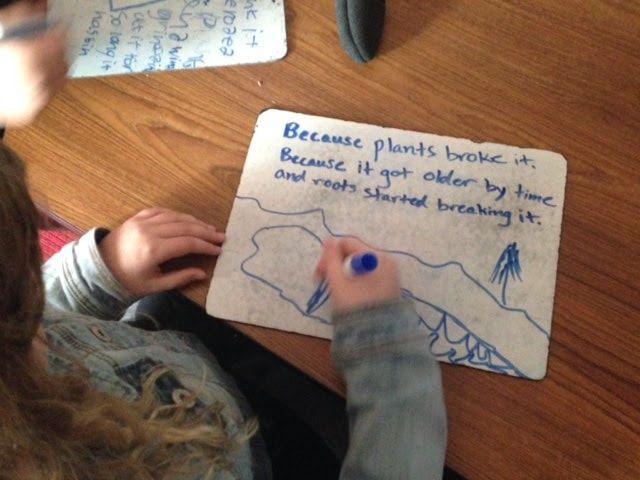

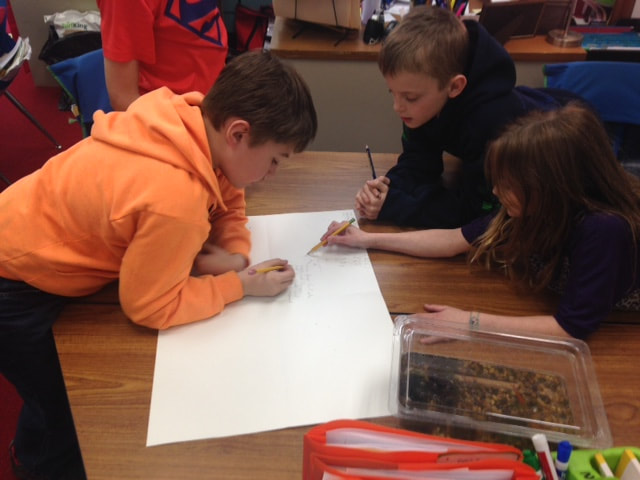

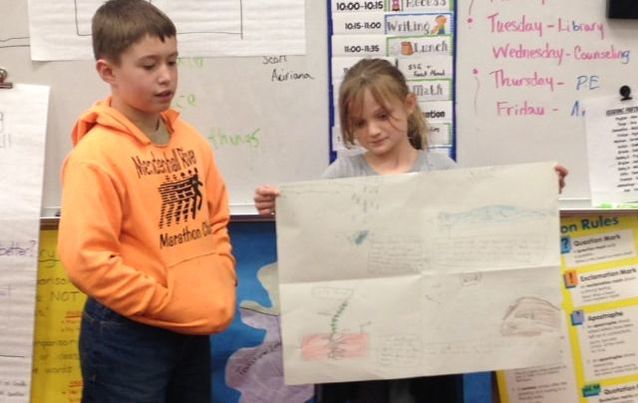

Most common responses to these questions were that CBRT helped them learn and it was fun! Many students also acknowledged that the repletion of rules reading through the scripts helped them learn better. Students were also given additional rehearsal time after the post test. The first day of the last week was our performance day. We invited other math classes to attend our performance and followed the outlined lesson below created by Roblin in preparation for the performance. Final Reflection:

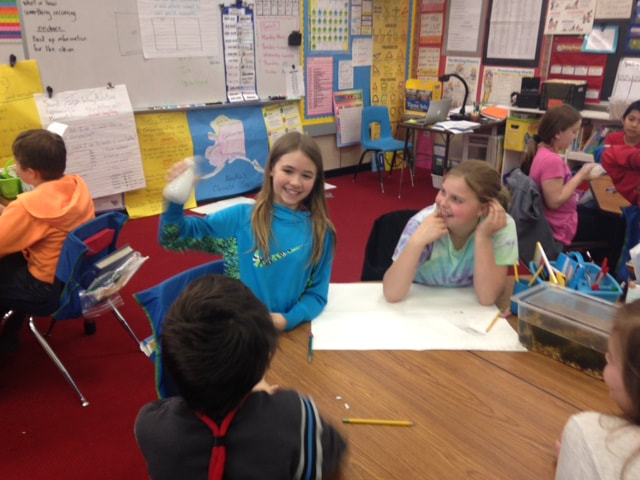

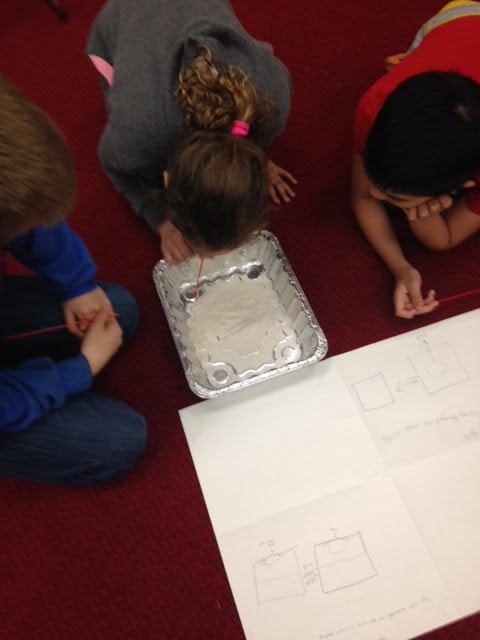

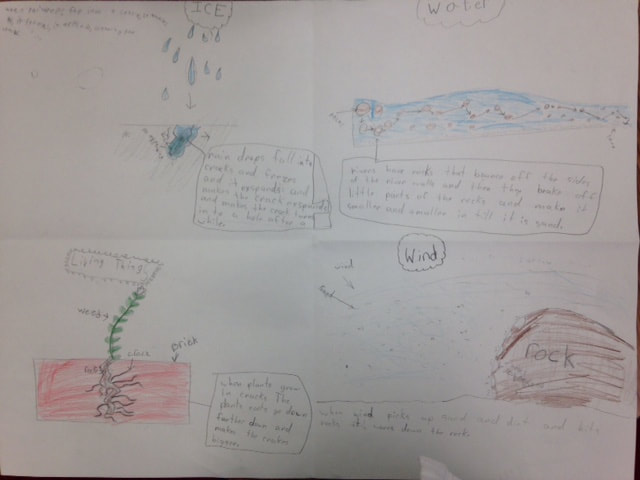

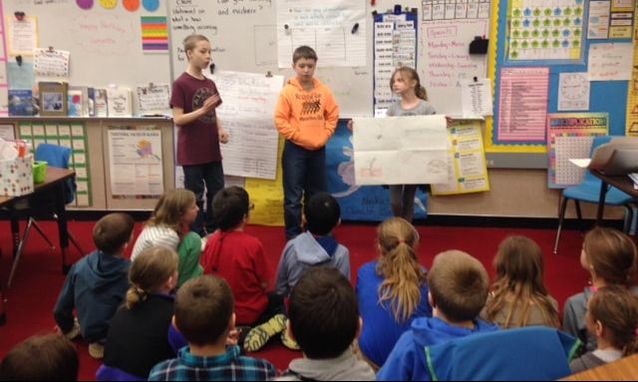

I really enjoyed the opportunity to learn about and implement a CBRT unit in mathematics. I was able to teach an advanced grade level concept to students at the end of the year while at the same time making the learning personally relevant, fun and totally engaging. Had I followed the sequence of the textbook for this unit, it would have taken me at least 17 class periods (55 minutes each) but with the entire CBRT unit it took less than 12. From the assessment results, I saw that it had a positive impact on student learning and from the comprehension questions as well as my observations, students really enjoyed the process. I am totally on board to try implementing CBRT in my mathematics classes much earlier in the school year and using it continually as a way to teach math through performance art. It was a real pleasure to be a part of this process and I hope other teachers are interested in trying it themselves. By Jennifer Heidersdorf 4th Grade, Mendenhall River Community School Student Thinking about this image: What do you see? I see sand and mountains. I see an arch. I see a rocks and a canyon with a hole. I see sandstone, orange. I see a rock with a hole in it. What do you think? I think it’s a desert. I think it has reptiles. I think the sun is going down. I think there’s a cave. I think the picture was taken in Arizona. I think there’s very little water. I think it’s really old. I think the rock eroded What do you wonder? I wonder if it’s a hot place. I wonder if it’s a canyon. I wonder if the shrubs are grass and if the arch will fall. I wonder where this picture was taken. I wonder if sand made the hole. I wonder if things got fossilized in the rocks. I wonder if there’s a road or cactus there. I wonder what’s beyond the rock. I wonder how it was created. While attending the NSTA Conference this spring and learning with other teachers on how to implement the NGSS (Next Generation Science Standards), I got excited and thought, "wow, this sounds a lot like the Artful Thinking routine of See/Think/Wonder". We ultimately want all students to observe things, think about why things work, and ask questions that will hopefully lead them to future investigations to find the answers. Presenting students with a phenomenon in the form of pictures or other media creates an opportunity for students to look with their eyes wide open and share their ideas in a safe, nonjudgmental environment. This approach has become a common practice in the way that I start many of my lessons in my fourth grade class. For this opening science lesson, I wanted students to view a variety of images while doing a See/Think/Wonder routine. As we went through these slides, I had students respond aloud and also in written form. I didn’t frontload the lesson or give students any more information then that; my hope was that it would lead to them asking questions and that they would find a common occurrence among the pictures. Students were eager to share and had a wide range of responses and questions. When we finished looking at the images the first time, I asked them to take a quick look at the slides again and see if they noticed a common occurrence happening within the images. I love the engagement of students when they talk about what they’re seeing, thinking, and wondering. By separating out the questions, the routine stimulates curiosity and helps students reach for new connections. I could see from the student responses that they had a deeper interest. Student Thinking about this image: What do you see? I see sand and mountains in the background. I see a big hole in the the standing rock. I see a rock that looks like a hand without fingers. I see a statue of the illuminati. What do you think? I think it’s in the middle of nowhere. I think wind carved the rock. I think something hides or gets in the shade in the big rock. I think there’s water. I think it’s 10,000 years old. I think the rock is not stable and it might fall. What do you wonder? I wonder if people live there. I wonder if the rock is going to fall. I wonder if it was flooded and then got dried out. I wonder what’s behind the rock. I wonder if I can fit in the rock. I wonder if somebody sculpted the rock. I wonder where this is. I wonder how it came to be. Student Thinking about this image: What do you see? I see a cliff holding a building. I see the tide has gone down. I see what would be the ocean. I see wet rocks, seaweed, and blue sky. What do you think? I think it was hard to get down to the beach. I think they’re going to rebuild the house. I think it’s in a foreign country. I wonder if the person taking the picture is underwater. I think there was war before the house was built. I think people would go there on the 4th of July. What do you wonder? “I wonder where the photo was taken. I wonder if I’ve seen it before. I wonder if there was a tsunami. I wonder if the house was a church. I wonder if the water wore the cliff down. I wonder what the people are doing. I wonder how long the building has been there.” Engagement and Enthusiasm What I love is hearing students make connections and but having them make those connections on their own. I didn’t want to give students any vocabulary, I just restated what they said and eventually a student said the word erosion. At that point I asked him what he meant by that and then we were able to substitute that word with a definition that tied into what they were observing but they made the connection on their own. From this point we talked about the different forms of erosion and how it can cause change. Science activities that followed: These lessons served as an entry point into NGSS standards 4-ESS1-1 (Identify evidence from patterns in rock formations and fossils in rock layers for changes in a landscape over time to support an explanation for changes in a landscape over time) and ESS1.C (Local, regional, and global patterns of rock formations reveal changes over time due to earth forces, such as earthquakes). To engage students in the topic of weathering the next day, I presented the class with a picture of an interesting rock formation and gave them the following prompt: With your whiteboard, please use sentences, labels, and drawings to propose an explanation for how you think this rock might have been hollowed out. Please explain how you think this occurred using sentences and drawings. Our Four Investigations Wind: Student groups are provided a container of sand and a drinking straw. Students then blow gently across the sand with the straw. The students are able to see the changes in the sand surface and observe the moving sediment. Students must wear goggles when working with sand. Moving Water: Each group is given a water bottle half-full with water. They then place a piece of chalk in the water and take turns shaking the bottle (moving the water). The students stop after three minutes and make observations. Ice: Students look at a picture (or a real example) of a bottle that was filled with water and then frozen. They can observe the expanded ice sticking out from the top of the bottle and the overexpanded bottle. Living Things: Students are given a baggy with a cracker in it. The cracker represents a rock. Students use their fingers to “weather” the cracker Students then worked in groups of five to propose explanations on a large sheet of paper that had been folded into four sections. I walked from group to group and asked clarifying questions about the science content on the boards (“Can you be more explicit in your drawing about how you think this occurs?”) and about the students’ writing (“Can you label your drawings and add more details using scientific words to explain your drawings?”). I then explained that I wanted each group to come to the front of the classroom, one group at a time, to present their ideas. But, before the first group came up, I directed the students’ attention to a poster on the classroom wall that outlines the group sharing norms that the class developed earlier in the school year. The list contains items such as: • Examine each paper carefully for words and drawings. • Can you identify claims and evidence? • What questions can you ask? • How does your paper compare to other papers? As I reflect on these lessons, I see how important it is for my students to be able to explain their thinking with drawings and explanations. As students observed the connections that other students made, many had some realizations that their paper didn’t look anything like other students papers. I wanted students to have a range of connections but well thought out connections. This is something that students have to practice at, it definitely does not come easy. I plan to start this strategy much earlier in the year next year to see just how much students improve and grow through the year.

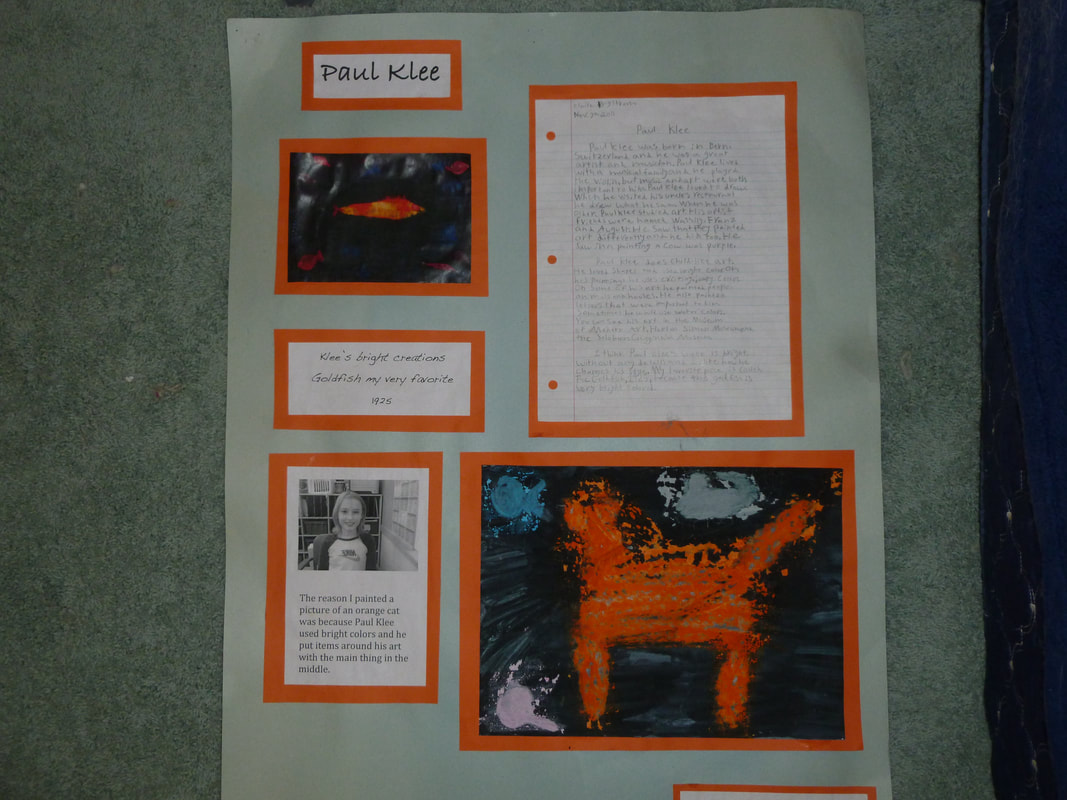

Observations by Becky Engstrom 3-5th Grade TED Specialist, Gastineau and Harborview Schools BACKGROUND As a specialist serving intermediate students grades 3 through 5, I have always rotated language arts units on a 3-year basis to be sure students are offered an eclectic mix of content supported by lessons to improve reading and writing skills. One of my favorite units has always been an art biography unit. Students would do research on an artist collecting pertinent facts by taking notes. They would use the notes to write a three paragraph report on their chosen artist. They would write haiku poetry about their artist and the art work. They would create a piece of work combining their artist’s style and beliefs with their own, then they would support the piece they created with a description explaining their reasoning behind their work of art. All these parts are then mounted on a poster board which has always made for a beautiful display. CHANGE After signing up and committing myself to the study of Artful Teaching, the first thing I wanted to do was change this unit to create more opportunities for authentic artful thinking using a variety of thinking routines from different thinking dispositions. I experimented with a selected artist to experience different routines that would help students when they finally selected the artist they wanted to study. I chose Frederic Remington to learn and model different thinking routines. We did a verbal See/Think/Wonder in table groups with different Remington pieces, then used the same pieces to do a verbal Beginning/Middle/End. We experienced Step Inside with a work from Remington. We studied desert vocabulary (mesa, plateau, canyon, butte, saguaro, ocotillo, etc.) and used that vocabulary to create tableaus. ON THEIR OWN After students selected their artist, gathered notes, and wrote their report, I selected a piece from their artist, printed it out, and students wrote their See/Think/Wonders on the printout. Students also selected a piece from their artist that they wanted to attempt to turn into a Tableau (step inside). The student who selected their piece would become the tableau director and had to put people in position until they were satisfied with the outcome. It gave me a good understanding of which students had excellent communication skills and which students needed improvement. It also helped me see the students who noticed many details and the ones who did not. I would have to bring focus to areas in the piece with questions… “What direction are they looking?” “What is their hand doing?” The amount of information I received from this one activity was a true eye-opener! Students also extended their thinking by creating a piece of art that connected their own thinking to the artist they were studying. CRITIQUING AN ARTIST Students wrote a research paper on the artist they picked. The last paragraph was their opinion of the artist they selected. I especially enjoyed reading these paragraphs. NEW PROJECTS DISPLAYED IN RETROSPECT

Although I believe the old poster board displays were more visually pleasing and beautiful, the new displays showed more artful thinking; the most beautiful moment to catch is proof of a brain in action. Whereas the old displays had more writing skills involved, the new supported the process by which learning took place. It was inspiring to watch the students make incredible observations. To listen to the details noticed to create the tableaus was a treat. To read their observations of the students’ chosen artist was deeply satisfying. Teaching became more passive, as if I handed the wheel to the students because they were ready to drive. It’s scary, and wonderful at the same time. By Allison Smith 1st Grade, Auke Bay School Artful Teaching has transformed the way I teach. One example is when we studied weather this year. In the past, when we studied about wind, students made wind flags measure the wind on a scale of 0-2. The flags are made from fabric and cardboard cut for them ahead of time. The emphasis in this lesson had been on the measurement of wind, not so much on the creation of the wind flag. This year I decided to use Artful Teaching to introduce the concept of wind and measuring wind by showing my first grade students different paintings showing wind and wind gauges. That got me thinking...if students are looking at pictures of different wind gauges, why not have them design and create their own wind gauges and test them? What started with me looking for images to introduce a lesson turned into a great STEM project for my students. First I asked students to See, Think, and Wonder looking at 4 paintings showing wind at the same time. Then I asked them to think about what was the same about all of the paintings. “It’s windy!” Was the common answer. Students then talked in small groups about how they knew it was windy. “The curtains are blowing.” "The horses’ manes and tails are blowing.” “The person is flying a kite.” Are a few of the things they shared. Our next step was to work in small groups to look at pictures of different tools designed to measure the wind. I explained to students that we would be looking at these wind gauges and asked them to discuss how they thought they worked. The conversation was lively with lots of pointing at parts of the pictures to explain how they worked. After students had a chance to look at and discuss how the wind gauges worked, I gave them the challenge of creating their own wind gauge by making a plan, building their wind gauge, testing their wind gauge using a fan, and revamping their wind gauge as necessary. It was an amazing process to watch and be a part of. Students were engaged in all parts of the project, taking time to create their designs as well as testing, revamping, and testing their gauges again. After our wind gauges had been tested and redesigned, students took them outside to measure the wind speed on a scale of 0-2. The student created wind gauges worked just as well as the flags we used to make! At the end of the project, I asked students to share what they learned. Here’s what stuck with me:

“If your wind gauge doesn’t work at first, change it and try again.” In the end, this lesson was just as much about the design and creation process as it was weather. Thank you Artful Teaching for expanding my horizons! |

ArtStoriesA collection of JSD teachers' arts integration classroom experiences Categories

All

|

|

|

Artful Teaching is a collaborative project of the Juneau School District, University of Alaska Southeast, and the Juneau Arts and Humanities Council.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed