|

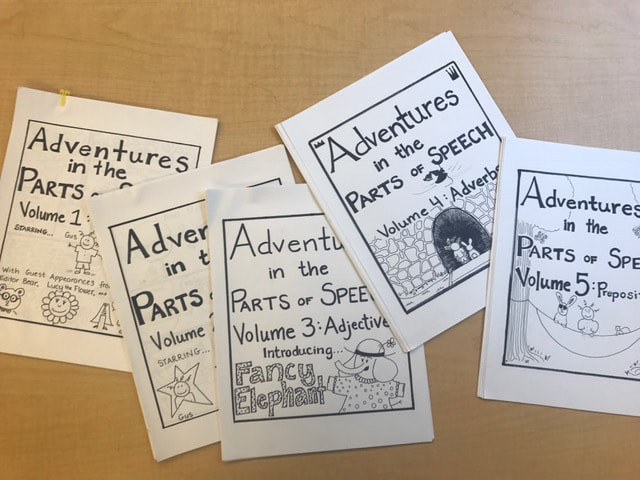

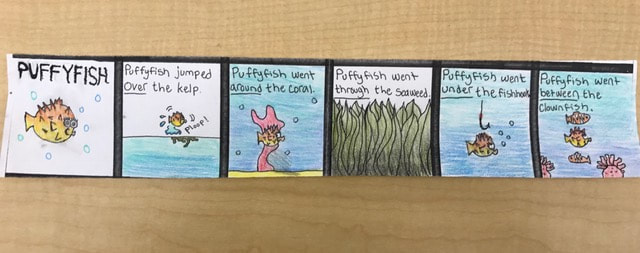

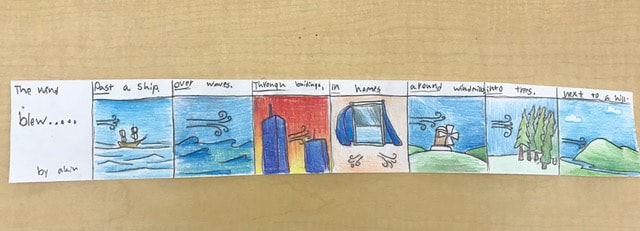

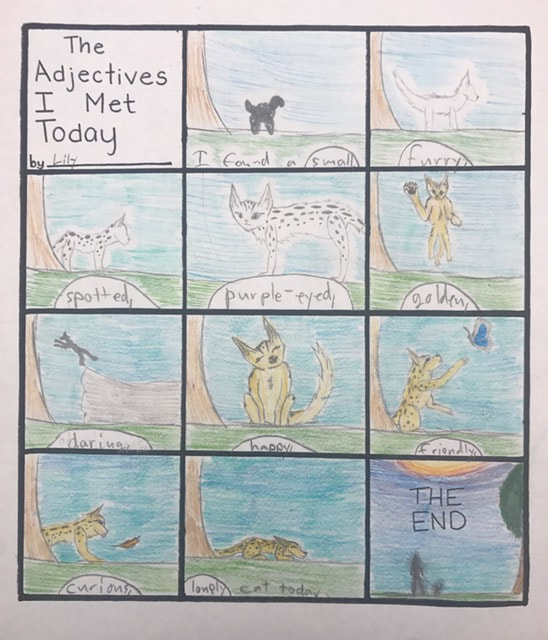

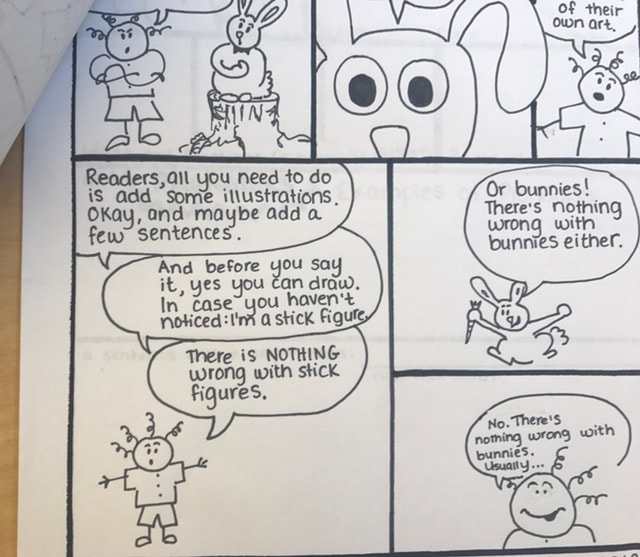

By Samantha Davis 8th Grade Language Arts, Floyd Dryden Middle School As I began my year in Artful Teaching, I was so excited to learn new ways of integrating arts into my eighth grade language arts classroom. During a fall unit about the parts of speech, I set a goal of working art into grammar instruction, both through the products students create to show their learning and through my own teaching methods. Though I eventually added in some of the strategies I was learning about in the Artful Teaching workshops, including tableau, I primarily focused on integrating comics into the parts of speech unit. Our learning objective was for every student to show their understanding of the parts of speech through a series of mini-comics. Because I wanted to begin our learning with a form that integrated art into instruction, I created short comic books introducing students to each of the eight parts of speech. As students moved through the unit, they learned to expect that each new concept would both begin and end with a comic: they’d learn about the part of speech through a comic, and they’d eventually produce a comic showing their understanding of the part of speech. We’d start by reading a comic about the part of speech aloud in class. Voices were strongly encouraged, and the actors in class often rose to the occasion, much to their classmates’ amusement. These comics not only introduced the content-area concept, it also forced me to take the same risk I'd be asking students to take: creating and sharing original artwork. This helped create a safe environment for creating and making mistakes. After we read the introductory comic, we’d discuss the part of speech, practice identifying it in different sentences, analyze why it matters in writing, and respond to writing prompts focused on that particular part of speech. Finally, students would show their knowledge of the part of speech through their own comics. The prompts for these comics were designed to encourage creativity, provide structure, and focus on the objective. For example, one comic was called, “The Adjectives I Met Today.” For this comic, students would pick a noun and invent a variety of adjectives for that noun to “meet.” Students used the artwork to (literally) draw connections between nouns and adjectives, thus representing the abstract concept of nouns modifying adjectives in a concrete, visual way. For the students’ preposition comic strips, the prompt involved picking a noun or pronoun and an action verb. Then, every successive frame had to be a prepositional phrase. Again, students were using art to demonstrate their understanding of an abstract concept. While the prompt and the prepared templates gave even more reluctant students the confidence that they could be successful, students were encouraged to extend and adapt the prompt as well. In every class, some students would take the initial prompt in new directions, without losing their ability to demonstrate their understanding of the content goals. In these situations, students would approach me with a proposal for another approach—“What if I…”—and we’d discuss how that approach would still work to show understanding of the content goals, or we’d modify it so it would still show the understanding while honoring the student’s unique approach. Some students were reluctant about their drawing skills. But stick figures were okay: after all, the star of “Adventures in the Parts of Speech” is a stick figure. In some ways, this approach to these projects helped establish a classroom culture where the expectation is not to avoid mistakes, but to try even when we’re unsure. Finally, one of my favorite moments of this unit--and in every unit in which students produced a piece of visual art--is the moment when the student work is displayed in the back of the classroom (our classroom gallery). Without fail, the day after their work is posted, students gather to observe the creations—always searching for their own, but also seeing how others responded to the same prompt in completely different ways. Often, they’re also assessing learning and asking new questions about the concepts. In the days and weeks after I post their work, I will often find students, on their own or with their classmates, browsing the gallery. So in this final stage, students are learning from each other.

So, why was it important for students to construct and demonstrate their understanding through the arts? First of all, I found students far more ready to engage with a pretty dry concept—the parts of speech isn’t exactly the stuff of fireworks—when it was introduced in the fun, humorous, and accessible medium of comics. Furthermore, when students began creating their own comics, it allowed for on-the-spot formative assessment along with natural extensions. It was easy to see which students had a mastery of the concept and which still needed more one-on-one instruction. Plus, with students so engaged in the project, it often gave me to provide that extra instruction as soon as I identified the need for it. Even more importantly, I’ve found that the use of art to show understanding builds community in the classroom. It forges connections: students who feel more confident in their artwork can encourage and support those who feel more apprehensive about their drawing skills, while students who felt more confident about their understanding of the content concept (in this situation, the parts of speech) can question and guide those who might still be confused. Comics--whether students are reading them or creating them--invite humor and conversation. In the classroom, as students worked on their comics, there was a constant buzz of conversation as they checked their understanding and ideas with each other. While everyone created their own comic, they worked together to create, sharing and exchanging supplies—“Can I use that crayon?” “No, I’m not done with it quite yet” “Oh, here, I have one you can use”—in ways that felt natural and needed no prompting from the teacher. Similarly, students began to use the artful thinking disposition of see-think-wonder before it’d been formally introduced, as they shared their work with each other, making observations and asking questions. The work was both individual and collaborative. When I think about this question, “Why was it important for students to construct and demonstrate their understanding through the arts?”, I think about these scenes: students gathering in front of the gallery to see, think, and wonder about each other’s work; students sharing art supplies and ideas; students laughing and celebrating each individual’s unique approach to a project. In short, when students construct their learning through the arts, it encourages both individual creativity and a supportive classroom community. Though I’m in my twentieth year of teaching, my participation in Artful Teaching has consistently provided me with new challenges, ideas, and inspiration over the course of the year; I’m already looking forward to building on all I’ve learned this year with next year’s students.

0 Comments

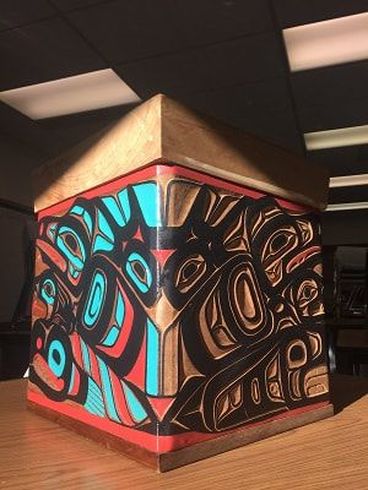

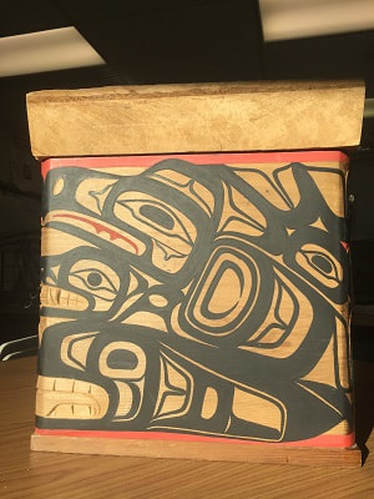

by Tennie Bentz Dzantik'i Heeni Middle School, 7/8th grade Bentwood Box created by Leroy Hughes Eighteen primarily Alaska Native students enter the classroom full of energy on this fall afternoon. Most of them struggle in math and it is the last class of the day, so no one is ready to buckle down to learn about measurement, surface area, volume, symmetry, or ratios and proportions. Then Ruby Hughes, our Cultural Specialist, brings in the most beautiful Bentwood Box any of us have ever seen. It is large, approximately 24 inches on each side. Intricate formline designs are carved on two sides and painted on the other two. The students settle down a bit and I start to hear sounds of excitement as they begin to look at and touch the box. They are hooked. Not only are they in the presence of a masterpiece, they are about to create their own. Students settle into their seats with the Bentwood box at the center of the room. We begin the I See, I Think, I Wonder thinking routine and discuss what students see when they look at the box. What makes this box so beautiful? Is it the size, the shapes, the colors, the symmetry? Groups look closely at the box and explain how they think the box was built. Some of our students have built one before so they can help explain the process to others. Many students wonder how they will ever be able to complete something so complicated. Step by step, we tell them. It’s going to be a long process, but in the end they will have a tangible item that they will be able to give as a gift or keep as a memory of the challenge to come. A couple of days later, Ruby brings each student their own rectangular piece of yellow cedar from Hoonah. Sealaska Heritage Foundation helped cover the cost of the cedar which is fairly expensive. Ruby explains the importance of precise measurement and we show students examples of boxes that were square and others that are not. Students see the beauty in symmetry. Perfectly bent corners, straight lines, tops proportional to the bottoms. Armed with a ruler, pencil and their new knowledge of measurement, students begin measuring precisely to ¼ and ⅛ and even 1/16 of an inch. Some of the students fly along, making their measurements while others fall behind. One girl starts to wander about the classroom bothering others. At first she won’t tell me why she is wandering and then I realize, she doesn’t know how to read her ruler. She’s never been asked to measure something so precisely, especially when mis-measuring by something as small as ⅛ of an inch will end up creating a box that is no longer symmetrical and square. This young lady would rather give up than end up with a less than perfect product. I convince her to sit back down and together we began to measure. We create a template because remembering which line is which on the ruler is too difficult for her on this day. Soon she has her measurements complete, her corner angles drawn correctly and the rest of the class finishes soon after. The project flies by. Day after day as students saw, sand, and chisel their way towards a final project. Ruby works patiently guiding half of the students through the process of building their boxes. I work with the other half of the class tying in the math behind the art. We learn about surface area by creating wrapping paper and volume by filling the example boxes with cubes. Fractional measurements are converted to decimals and percents. Standard systems of measurement are converted to metric. On and on the math goes with students always excited to stop with the math so they can just go work on the art. Soon the boxes take shape. Ray Watkins visits Dzantik’i Heeni and he and Ruby take a few kids at a time downstairs to steam and bend the boxes into their square shape.The other students wait impatiently with me. They want to see if all of their precise measurements and persistence sawing and chiseling have paid off. Will their final product have the lines of symmetry and the perfect bends in the corners? Soon students begin to carry the boxes back upstairs, smiles on their faces. Most of the boxes are nearly perfect, a few aren’t quite square but Ruby is sure that she and Ray can magically fix them overnight. The next day, when the students return, everyone has a perfect box. Soon the students began new measurements to create perfectly fitting bottoms and proportional tops. The boxes were nearing completion for many students. The experience of building their own Bentwood box was enough. Others however wanted to take the box further and create their own formline design to put on the outside. We spent some time looking at the Colors, Shapes and Lines on the masterpiece Bentwood Box that had served as our inspiration through this entire process. The colors were few but bold. Red, black, teal and natural wood. Ruby taught us the names and relationships between the shapes. Ovoids serve as the center from which U-shapes extend. We learned that the shapes rarely stand on their own, but connect and flow from one form to another. To me this was the perfect analogy for how math should be taught. Fractions should not stand on their own, there needs to be flow, a relationship and connection between the math and real life application. This was the perfect opportunity to teach ratios, proportions, similar and congruent figures and lines of symmetry through art. Ruby taught the students how to make ovoids using lines of symmetry and I created an activity where they had to measure the height and width of the ovoids and then create new ovoids that were similar using ratios and proportions. Most of the students ended up with a set of ovoids that they could use as a template when creating the formline design on their boxes. Some students quickly realized that they could avoid the math and just draw ovoids within ovoids to create their template. Whichever method students chose to use, the concept behind math supporting art was cemented. Students are still working on their formline designs. One young lady is trying to get in touch with her grandparents to learn more about her lineage so she can put the correct clan crests on her box. She is an inspiration to me and reinforces the need for more projects like this one. She doesn’t do much in math class and did very little of the work when we worked with the math behind the art. Some may call this a failure of the project when looking at it from a math perspective but this student is so proud of the masterpiece that she created that she is taking the time to make sure the connection to her family’s history is accurate. She plans to give her box to her grandmother in Angoon. That in itself proves the project was successful in my eyes. Acknowledgments:

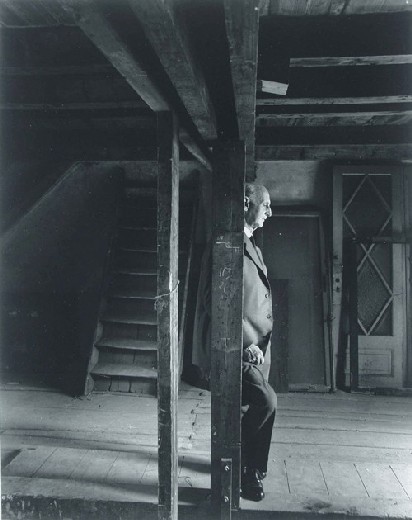

I owe a huge thank you to Ruby Hughes. Her calm presence and patience was an inspiration through this process. Without Ruby’s help and support, this project would have been a disaster. Ray Watkins’ help behind the scenes made this project streamlined and successful as well. Thank you to Sealaska Heritage Institute for your generous support providing the yellow cedar and to the Artful Teaching grant for purchasing colored pencils for the final box designs. by Tracy Goldsmith Dzantik'i Heeni Middle School My 8th grade Language Arts class students studied the Holocaust. They were assigned different Holocaust novels to read and they participated in literature circles using those novels. We started the unit by using the Step Inside Artful Thinking Routine with this image; This is an image of Otto Frank, on the opening day of the Anne Frank House as a museum in Amsterdam. I asked students to stand up and quietly place themselves into the same position as the person in this portrait. While they quietly, stood in position looking at the image, I asked them to image what this person might be thinking or feeling. I wanted them to come up with a story about this picture and this man. They stood silently for one minute and then they had to write a journal entry answering the same questions. Some student responses are below:

The unit involved many different activities related to the Holocaust. One resource we used extensively was the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum website (www.ushmm.org). To extend the Artful Thinking routine of “Step Inside,” the students were assigned a portrait and first person narrative project. They started by finding one victim or survivor whose story they wanted to explore more on the USHMM website. There is a link on the website that shows ID cards with pictures and information about victims and survivors. After finding a person that they wanted to study more, students had to read the information about them and then turn that into a first person narrative. This first person narrative would be read out loud to the class later in the unit. The activity of writing in first person really stretched their understanding of what an individual was experiencing during the Holocaust. Being able to read it out loud to an audience, made that story come alive. Many students were emotionally touched by the narrative readings.

|

ArtStoriesA collection of JSD teachers' arts integration classroom experiences Categories

All

|

|

|

Artful Teaching is a collaborative project of the Juneau School District, University of Alaska Southeast, and the Juneau Arts and Humanities Council.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed